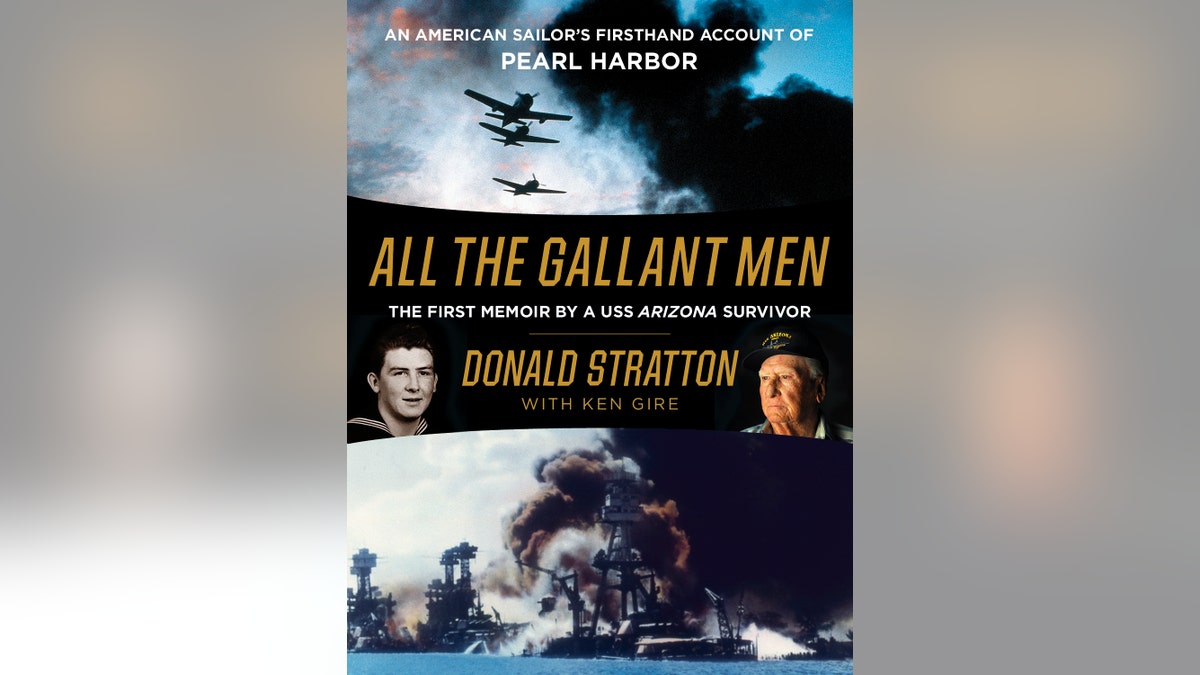

Editor's note: The following column is adapted from "All the Gallant Men: An American Sailor's Firsthand Account of Pearl Harbor."

I was aboard the USS Arizona on the morning of December 7, 1941. The courage I saw in our men was astonishing.

Those gallant sailors fought back however they could. Pilots tried to locate airplanes that were still operable, but only a few managed to get in the air and into the fight.

Gunners found themselves with only the ammunition in their ready boxes, with the rest of the munitions they so desperately needed locked up belowdecks.

What happened on December 7, 1941, if it didn’t kill us, changed us forever. President Roosevelt was right to call it “a date that will live in infamy.” But for my fellow survivors and me, it also is alive in memory, like shrapnel left embedded in our brains because the surgeon thought it too dangerous to operate. These memories lie within me, forever still and silent, like the men entombed in the Arizona.

If the bullets ran out, they raced to another gun, often one that had a fallen sailor crumpled beneath it.

The rest of the men fought back with whatever weapons were at hand, shooting at the streaking Japanese Zeros with lightweight machine guns, rifles, even pistols.

Acts of individual heroism could be witnessed everywhere you looked. Men being strafed as they brought boxes of ammo up ladders to the antiaircraft guns. Other men carrying their wounded buddies to safety, trying desperately to stanch their bleeding. Still others in small boats, navigating through the fiery sea, pulling oil-soaked sailors from the water. Many putting out fires on board their ships. All the while these men were dodging enemy bullets that were cutting everything around them to shreds, including their fellow sailors.

We were not extraordinary men, those of us who fought on that infamous date in December seventy-five years ago.

Truth be told, most of us had enlisted because there were precious few jobs to be found where we lived. The Great Depression had pulled the pockets of the economy inside out, leaving little more than a lint’s worth of hope for the young men entering the workforce. Most of us who enlisted did so because we needed a job.

Pearl Harbor changed that. A surge of patriotism swept the country, and everyone threw themselves into the war effort.

Love for country welled up inside seemingly every American, coming out in the songs we sang, in the movies produced, in the newspaper articles that were written.

We were ordinary men. What was extraordinary was the country we loved. We loved who she was, what she stood for. We loved her for what she meant to us, and for what she had given to us, even in those meager times.

It didn’t matter where you hailed from, whether you came from the mountains or the prairies, a sprawling city or a small coastal town: you loved her.

We all did—more than the states we left behind, our homes, the careers we gave up. As too many would prove, we loved her more than our very lives.

The battleships and destroyers at Pearl Harbor were named after states from where some of us had been raised. Ohio. Tennessee. Oklahoma. Maryland. California. West Virginia. Utah. Nevada. Those vessels moored in that harbor so far from home reminded us where we came from.

The battleship I served my country on was the USS Arizona.

The men on that ship were drawn from different parts of the country. Some came from family farms in the Midwest. Some were fresh from the steel mills of Chicago. Others joined from dirt-poor towns in the Deep South. A few arrived with book smarts from places foreign to the rest of us—Annapolis, Notre Dame, Vanderbilt.

They came from different religious backgrounds. Some were Catholics, some Protestants, some Jews. Others weren’t sure what they were. A few didn’t care. After all, many were still teenagers with their whole lives stretching before them. There would be plenty of time for religion, later.

They came from different ethnic backgrounds, too. Their accents betrayed them.

There was a Jastrzemski from Michigan.

An O’Bryan from Massachusetts.

A Schroeder from New Jersey.

A Giovenazzo from Illinois.

A Riggins from California.

A Nelson from Arkansas.

A Smith from just about everywhere—Virginia, Missouri, Florida, Illinois, California, Ohio, Tennessee, Arkansas, Texas, Oklahoma, Mississippi.

And a Stratton from Nebraska.

What happened on December 7, 1941, if it didn’t kill us, changed us forever.

President Roosevelt was right to call it “a date that will live in infamy.” But for my fellow survivors and me, it also is alive in memory, like shrapnel left embedded in our brains because the surgeon thought it too dangerous to operate.

Those images remain with us survivors seventy-five years later. Sometimes they intrude into our day, a moment spontaneously combusting, and suddenly we are back in the flames that engulfed our ship or in the oil-slick waters that surrounded it.

Sometimes they come to us in the night, a haunt of images that troubles our sleep. Or perhaps the phone rings, and we flinch. Or a car backfires, and instinctively we duck.

These memories lie within me, forever still and silent, like the men entombed in the Arizona. Others, like the oil that seeps from its wreckage, slip around inside me until they find a way out and make their way to the surface, where they pool and sometimes catch fire.

Over the years, many of us made the pilgrimage back to that harbor, where we have experienced both the soothing of those wounds, and, at the same time, a reopening of them.

Have some been healed? Yes. Year by merciful year. But all? No. And that is true for so many who have survived trauma, not just those who have survived the horror of war.

With each anniversary our ranks thin.

Three hundred thirty-five Arizona sailors survived that day.

Only five remain.

I am looking forward to reuniting with them on the seventy- fifth anniversary of Pearl Harbor in December 2016.

Realistically, though, I realize I am about out of anniversaries. At ninety-four, I don’t take the years ahead for granted. Not one.

More than 65 percent of my body was burned in the explosion that sank the Arizona. My body is a patchwork of scars and skin grafts. Much of the feeling has come back. But not all.

My joints are stiff, and I have to push myself up from my chair, then steady myself before I take the first tentative step.

It’s been said that when an old person dies, it is like a library burning down. Having survived a fire that took so much from me, I have an obligation to save what memories I have from the flames that will one day come and claim what is left of me.

I share what I remember when I can. But a day will come when I can no longer speak. What then? I have asked myself. What will become of the memories that I as a survivor have experienced? Or the lessons that we as a nation have learned?

That is why I wrote my book, which we titled "All the Gallant Men" as tribute to those whose lives were claimed seventy five years ago.

I wanted to save from the fire something of my memories of the Arizona so that younger generations, and all of the children to come after them, can understand why Pearl Harbor matters.

Though my memory is pretty good, here and there I have needed to augment it with research, and I am indebted to those sources that helped clarify my recollections.

Most of the memories are my own, but I didn’t want the story to be exclusively mine.

It’s important to me that the experiences of my shipmates and of other sailors, soldiers, and Marines who fought that day be included. They deserve to be heard, even though they are gone.

Especially because they are gone.

Excerpted from "All the Gallant Men: An American Sailor’s Firsthand Account of Pearl Harbor" by Donald Stratton with Ken Gire. (William Morrow, November 22, 2016).