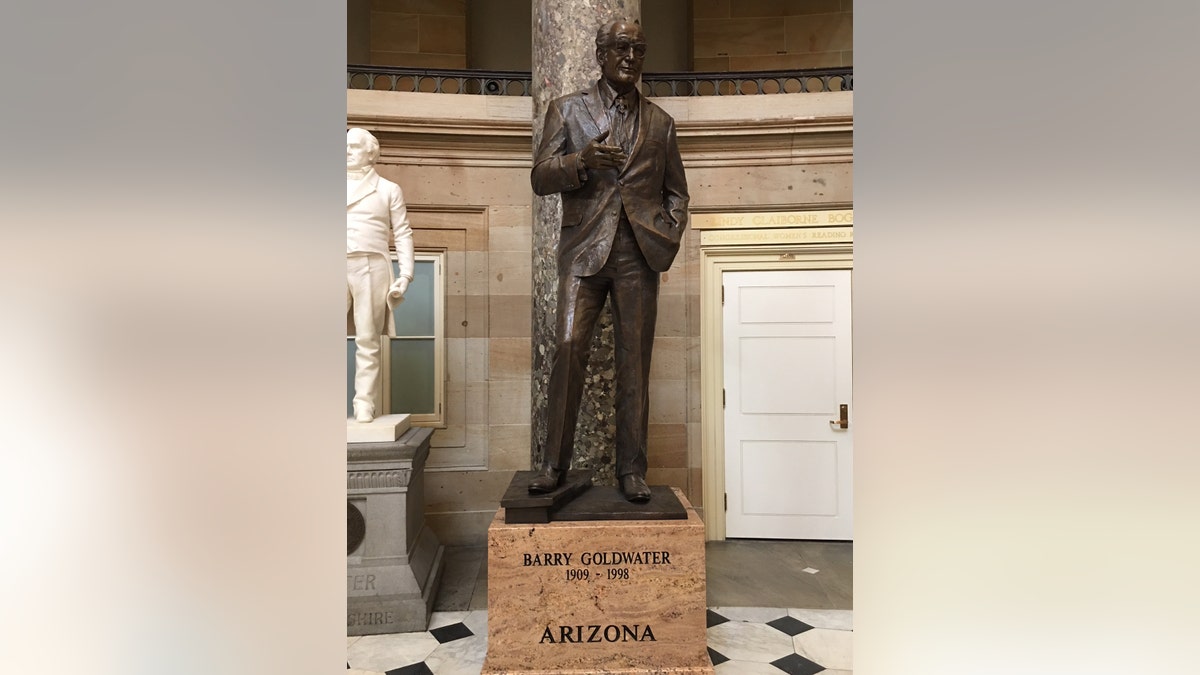

The statue of Sen. Barry Goldwater, R-Ariz., in the Capitol’s Statuary Hall. Goldwater was Sen. JOhn McCain’s Senate predecessor. (Chad Pergram/Fox News)

The U.S. Capitol is quietest early on a Sunday morning.

No lawmakers. No aides. No tourists. No lobbyists. No journalists.

Not even overnight maintenance crews, curators or custodial workers.

Sunday is the one day of the week when the public can’t tour the Capitol. The Senate left town last Thursday and didn’t return until late Monday afternoon. The House remains on a five-week hiatus.

The Capitol subsists in solitude on Sunday morning. Recuperating. Breathing. Bereft of the hair-on-fire bustle which dominates the other days.

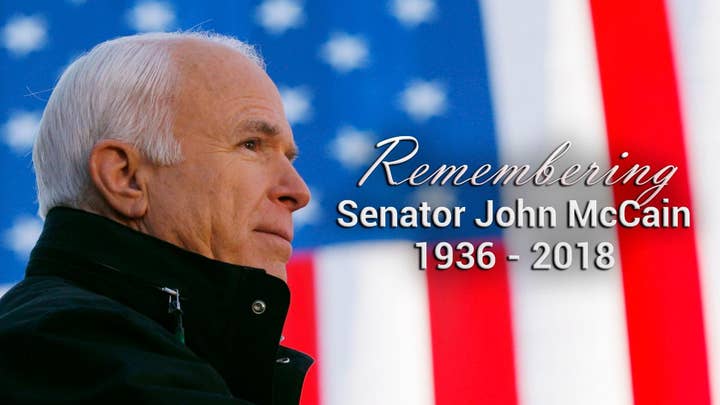

A deafening hush cloaked the vacant Capitol in the wee hours of Sunday morning. I was there to report on the Saturday night death of Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz. I passed a couple of U.S. Capitol Police officers in the underground tunnels and at the door. But as far as I could tell, we were the only people present in the immense expanse of the most-famous building in the world.

I cut through the center of the Capitol Rotunda, a cavern of emptiness on Sunday morning. That’s a stark contrast to the transformation the Rotunda will experience. The nation will focus its attention on the middle of the Rotunda on Friday.

That’s where the casket bearing McCain’s remains will rest atop an ancient, black wooden platform. McCain will become the 30th person to ever “lie in state” in the Capitol Rotunda. The first was former House Speaker and Kentucky Senator Henry Clay in 1852. The most recent was Sen. Daniel Inouye, D-Hi., in December, 2012.

I paused for a moment to construct the tableau in my mind’s eye. I culled scenes I witnessed from ceremonies for Inouye, President Reagan and President Ford.

The coffin. The honor guard. The family. The public.

And I always remember the sound. The muffled shuffling of feet as the crowd pinwheels around the casket.

However, on Sunday, my destination wasn’t the Capitol Rotunda. I wanted to snap a picture of the statue of Sen. Barry Goldwater, R-Ariz., in the Capitol’s Statuary Hall. Goldwater was McCain’s Senate predecessor. Only Goldwater and McCain have held this particular Arizona Senate seat since January 3, 1953.

McCain came to the Senate in 1987 after two-terms in the House. McCain was stepping into the shadow of a legend in Goldwater. Yet their careers featured symbiotic parallels.

Both earned the Republican nomination for president and lost. There were questions about whether both men met the Constitutional qualifications for president.

The Constitution requires the president be “a natural born citizen.” Goldwater was born in “Arizona Territory” before it was admitted to the union in 1912. McCain was born in the U.S. Panama Canal Zone. Both chaired the Senate Armed Services Committee.

I arrived at the Goldwater statue and stared for a moment. And in the Sunday silence of Statuary Hall, I heard something.

A singular sound echoing off the marble of the Capitol. Not white noise, filling the acoustical void. There was no air conditioning blowing. No fan. No distant sound of a vacuum, or car horns, or voices ricocheting around the columns. Just a solitary ticking, inaudible during the daily commotion at the Capitol.

A statue of Clio is perched atop a doorway leading from Statuary Hall to the Speaker’s Office and the Rotunda.

Clio is the “muse of history.” Appropriately, she stands in a winged “Car of History.” The face of a clock doubles as one of the wheels of the chariot or car. Clio’s “car” signifies the unflagging march of time.

A statue of Clio leads from Statuary Hall to the Speaker’s Office and the Rotunda. (Chad Pergram/Fox News)

From her vantage point above the passageway, Clio stares at the Congressional comings and goings below her. She clasps a book in her left hand, documenting the events she witnesses in her journal.

The sound I heard emanated from the wheel of Clio’s history chariot.

Tick.

Tick.

Tick.

Of course. The clock on the wheel of the chariot, positioned dead center above the doorway. The daily chaos which consumes the Capitol typically dampened the ticking. But this was Sunday morning. Sure. The ticking was muted. But there it was. A tiny sound. The only audible thing in the cavernous, empty Capitol.

The silent desolation of the building seemingly ballooned the milliseconds between each tick, filling a temporal chasm which seemed longer than a second. And just when you thought the next tick wouldn’t come, there it was.

Sharp.

Staccato.

Deliberate.

The ticking reminded me that the longer I stood there, I was losing time. The Capitol was barren, otherwise frozen in suspended animation. But appearances can be deceiving. Time wasn’t stopping.

John McCain ran out of time the night before. His passing - and Clio’s ticking clock -made me think of a scene I observed on many occasions.

I covered McCain for years. I’ve seen a blue ink pin explode on his starched, white dress shirt. I’ve been shouted down by McCain for asking questions too aggressively. I’ve talked baseball and hockey with him at length. But what I remember most about McCain is that he was always in a hurry.

After votes on the Senate floor, McCain would dash down to the Senate subway station, hustling to a hearing or an important meeting in his office. If the subway wasn’t there, McCain would hit a little call button nearby to summon the car. You’d hear the ring, alerting the subway driver that the car was needed on the other end. But, more times than not, the subway didn’t come fast enough for McCain. So, he’d impatiently press the button again. And then a third time. Maybe a fourth, practically punching it.

Sen. John McCain was known to always be in a hurry, and would hit a little call button nearby to summon a car in the Senate subway station. (Chad Pergram/Fox News)

Like an elevator, pressing the button multiple times didn’t accelerate the arrival of the subway. I often wondered if McCain was always in such a rush to make up for his years of captivity in Vietnam.

“John’s entire approach to life was we want to get the most out of the time that we have,” said former Senate Minority Whip Jon Kyl, R-Ariz., on Fox. “He certainly did get the most out of the time he had here.”

The last time many saw McCain at the height of his powers came last October after four U.S. servicemen died in an ambush in Niger. And McCain was in a hurry. As Chairman of the Armed Services Committee, McCain grew frustrated that the Pentagon couldn’t provide answers about what happened.

“I want to talk to the head of Cyber,” seethed McCain, a reference to the U.S. Cyber Command.

Cyber Command could provide satellite and drone imagery about what went down. But McCain’s frustrations multiplied after he got little information. Days spilled off the calendar. McCain threatened to subpoena military officials if they didn’t offer some explanations post-haste. McCain’s ultimatum prodded Defense Secretary James Mattis to promptly pay a visit to the office of the Armed Services Committee Chairman.

McCain didn’t have time to wait around. Perhaps in more ways than one. He lost a lot of time in Vietnam. To McCain, every moment was precious. Fleeting. And he didn’t have a moment to spare.

Back in Statuary Hall, the clock on the chariot wheel ticks. The seconds melt unrelentingly into the silence. What will Clio scribble down in her book?

McCain’s death reminds us we’re all on the clock. He was running out of time.

And we are, too.