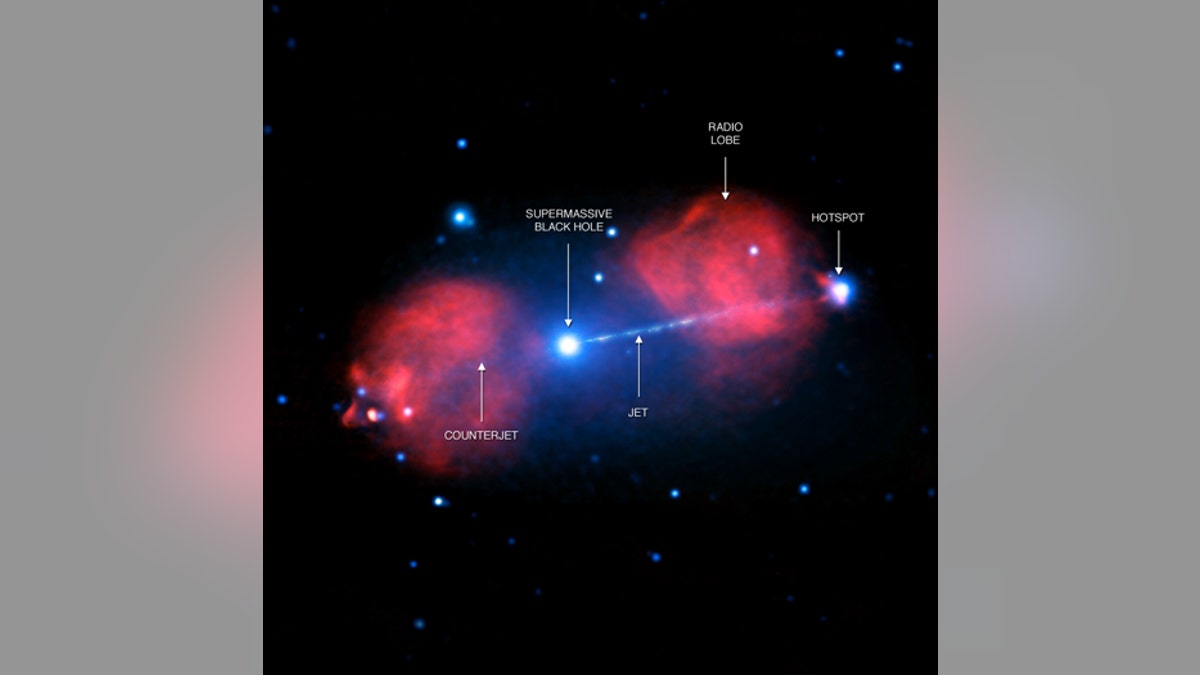

The Pictor A galaxy has a supermassive black hole at its center, and material falling onto the black hole is driving an enormous beam, or jet, of particles at nearly the speed of light into intergalactic space. This composite image contains X-ray data obtained by Chandra at various times over 15 years (blue) and radio data from the Australia Telescope Compact Array (red). ( X-ray: NASA/CXC/Univ of Hertfordshire/M.Hardcastle et al., Radio: CSIRO/ATNF/ATCA)

Imagine spotting the laser beam from the fictitious Death Star of “Star Wars” fame as you scan a distant galaxy.

That comes close to what an international team saw as they surveyed the Pictor A galaxy. Not only did they find a supermassive black hole in the galaxy about 500 million light years away but were able to study something even more stunning – a huge amount of gravitational energy streaming from the black hole and forming a visible beam or jet.

The beam, compromised of particles traveling nearly the speed of light into intergalactic space, stretched for a distance of 300,000 light years – three times the diameter of the entire Milky Way.

Related: Rare galaxy found with 2 black holes - one starved of stars

“We’ve known these jets exist for many, many years and the jet in Pictor A is a particularly good example because the galaxy that is generating happens to be particularly close so we can see it really well,” the University of Hertfordshire’s Martin Hardcastle, a lead author on a study of the discovery in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, told FoxNews.com.

In addition to the prominent jet seen pointing to the right in the image, researchers found evidence of one pointing in the opposite direction, known as a “counterjet.” The counterjet, which is much fainter than the jet due to its motion away from the line of sight to the Earth, had been previously reported.

But Hardcastle and his colleagues are the first to confirm its existence. “We are confident it’s there,” he said.

Related: Discovery of black hole 12 billion times bigger than the sun challenging growth theories

To obtain images of this jet, scientists used NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory at various times over 15 years. Chandra’s X-ray data (blue) have been combined with radio data from the Australia Telescope Compact Array (red) in this new composite image seen here.

By studying the details of the structure seen in both X-rays and radio waves, scientists seek to gain a deeper understanding of these huge 'blasts.'

Scientists believe the jet is formed from material on the edge of the black hole and that that their X-ray emission likely comes from electrons spiraling around magnetic field lines, a process called synchrotron emission. These charged particles go round and round, emitting radiation, which allows scientists to see the jet.

“What can happen is that the rotation of the black hole itself can twist up magnetic fields and the energy put into those twisted magnetic fields generates a column of energy going out,” Hardcastle said.

“I like to think of these things a bit like a garden hose,” he continued. “To drive any water through a garden hose, you need pressure on the end so that when you turn the tap on, the water will start will going out. In the same sort of way, once you start this process of sticking energy into magnetic fields close to the black hole, that builds up pressure and material is pushed out.”

The goal of studying these jets, Hardcastle said, is to better understand the black hole's interaction with its environment as well as what the jets are made of, how fast the material is moving and “how much energy is being carried up.”

Related: Could this be the second largest black hole in the Milky Way?

“These things are phenomenally energetic as you can imagine since we can see them for all this distance,” he explained. “We are talking vast energy comparable to the output of a quasar but in the form of material that is actually flowing, actually moving along.”

But can these jets of energy one day be harnessed for a Death Star-like weapon?

“There is a lot of energy there, but you know it’s not particularly safe to tap,” Hardcastle said. “An active galaxy like this is not a great environment to be.”

Pointing to work he has done in the past, Hardcastle said the best hope is that a jet like the one they observed remains as far away as possible. Should one impinge on the Milky Way, Hardcastle said it would be "really bad news.”

“If you have a planet like the Earth, you basically start to ionize the atmosphere. That means x-rays from the Sun can suddenly reach the ground and life is wiped out on planets all over the place," he said. "And since these things can last hundreds of million years, you can’t just go into a bunker and wait for it to go away. Our best hope is that we never have anything of this sort going on in the Milky Way.”