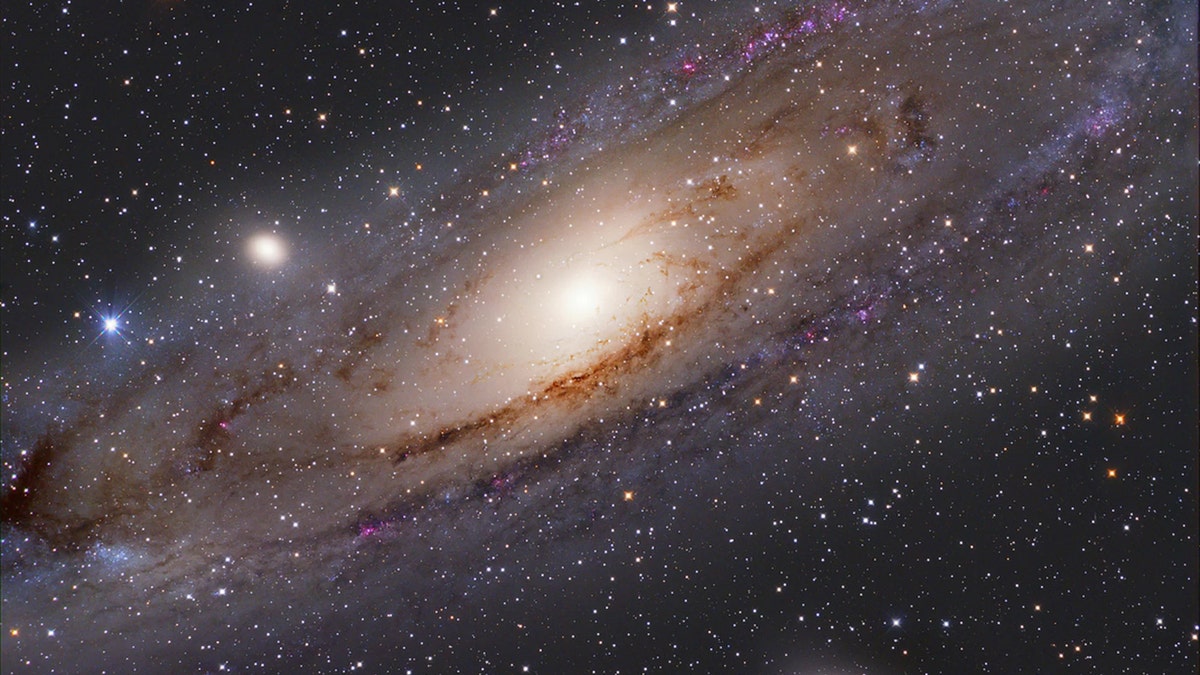

The Andromeda galaxy, with satellite galaxies M32 (center left) and M110 (lower right). A new study suggests that M32 is the remnant of a much larger galaxy gobbled up by Andromeda about 32 billion years ago. Credit: S. Ozime

The Milky Way had a previously unknown big sibling that was torn apart by the neighboring Andromeda galaxy long ago, a new study suggests.

Andromeda and the Milky Way are the two largest members of the Local Group, a collection of more than 50 galaxies packed into a dumbbell-shaped region of space about 10 million light-years across. Andromeda was not kind to the onetime third-biggest member of this family, devouring it about 2 billion years ago, according to the new research.

"Astronomers have been studying the Local Group — the Milky Way, Andromeda and their companions — for so long," study co-author Eric Bell, a professor of astronomy at the University of Michigan (UM), said in a statement. "It was shocking to realize that the Milky Way had a large sibling, and we never knew about it." [When Galaxies Collide: Photos of Great Galactic Crashes]

Andromeda, also known as M31, is a prolific cannibal; the huge spiral galaxy is thought to have shredded hundreds of its smaller kin over the eons. The number and complexity of these mergers makes it tough to tease out the details of any particular one — but Bell and study lead author Richard D’Souza, a postdoctoral researcher at UM, were able to do just that.

Using computer simulations, the duo determined that most of the stars in the faint outer reaches of Andromeda's "halo" — the roughly spherical region surrounding the galaxy's disk — came from a single smashup.

"It was a 'Eureka' moment," D'Souza said in the same statement. "We realized we could use this information of Andromeda's outer stellar halo to infer the properties of the largest of these shredded galaxies."

Further modeling work allowed them to date the merger to about 2 billion years ago, and to reconstruct some basic details of that long-dead galaxy. M32p, as the researchers call it, was likely at least 20 times bigger than any galaxy that the Milky Way has ever merged with, the new results indicate.

And M32p is apparently not completely gone. D'Souza and Bell think that an odd satellite galaxy of Andromeda called M32 is the lost galaxy's corpse — the bones left behind after the big, nasty spiral munched off M32p's meat.

"M32 is a weirdo," Bell said. "While it looks like a compact example of an old, elliptical galaxy, it actually has lots of young stars. It's one of the most compact galaxies in the universe. There isn't another galaxy like it."

The timing of the merger matches up as well. Another research team independently determined earlier this year that Andromeda likely underwent a big merger, and a concomitant surge of star formation, between 1.8 billion and 3 billion years ago.

The new study, which was published online today (July 23) in the journal Nature Astronomy, should help scientists better understand the evolution and effects of galaxy mergers, D'Souza and Bell said.

For example, it has long been assumed that huge crashes destroy the disks of spiral galaxies, turning these gorgeous objects into rather drab elliptical galaxies. But Andromeda has retained its spiral disk, suggesting that the conventional wisdom does not always hold.

As dramatic as the Andromeda-M32p collision likely was, something much bigger is on the horizon. About 4 billion years from now, the Milky Way and Andromeda will come together in an epic crash that will shake up the Local Group. The merger will spark some pretty impressive star-formation fireworks in Earth's night sky, if anyone's still around to see it.

Originally published on Space.com.