Developers look to make Deep South a tech hub

Young entrepreneurs and developers in Mississippi are aiming to make the Magnolia State a major techhub for the emerging field of virtual reality.

CLARKSDALE, Miss. – This agricultural town in the Mississippi Delta, in a region that is one of the poorest in the country, is thousands of miles away from California’s Silicon Valley. But in an old building here that used to be a clothing shop, there’s a virtual reality academy that trains the next generation of game developers.

Vince Jordan and his son, Josiah, founded Lobaki Inc. with the goal of creating a pipeline of young virtual reality curators and entrepreneurs from underserved and poverty-stricken areas.

“I’ve been going around to the schools in these poorer communities and saying, ‘If we replicate what I’m doing here we’re going to give these young people an opportunity that they would never see otherwise,’” Vince Jordan said. “Right now, any town, any state could take a leadership position in this and create the workforce of the future to really drive this out into industry, into education, into healthcare…I really do believe it could have a material impact on Mississippi.”

Members of the Lobaki Inc. team pose for a photo outside their office in downtown Clarksdale, Miss. (Left to right) Michael Bezzina, Mya Calhoun, Wendy Farley, Deuntay Williams, Shalin Jewett, Vince Jordan and Vinny Jordan. (Fox News)

According to a 2016 report conducted by Goldman Sachs, virtual reality technology could reach 15 million students by 2025, which highlights a growing need for new talent.

Jordan and his family relocated to Clarksdale from Colorado after meeting some of the current “VR curators” during a trip to the area in 2017.

Lobaki Inc., in partnership with a nonprofit created by the Jordans, relies heavily on grants and VR projects from companies and local schools to keep the academy running. Jordan said he has relied on personal savings to pay for expenses for himself and his family.

“Nobody here has had a salary in over a year. I know, it’s crazy,” Jordan said with a laugh and tears in his eyes. “Anything worth doing is worth doing.”

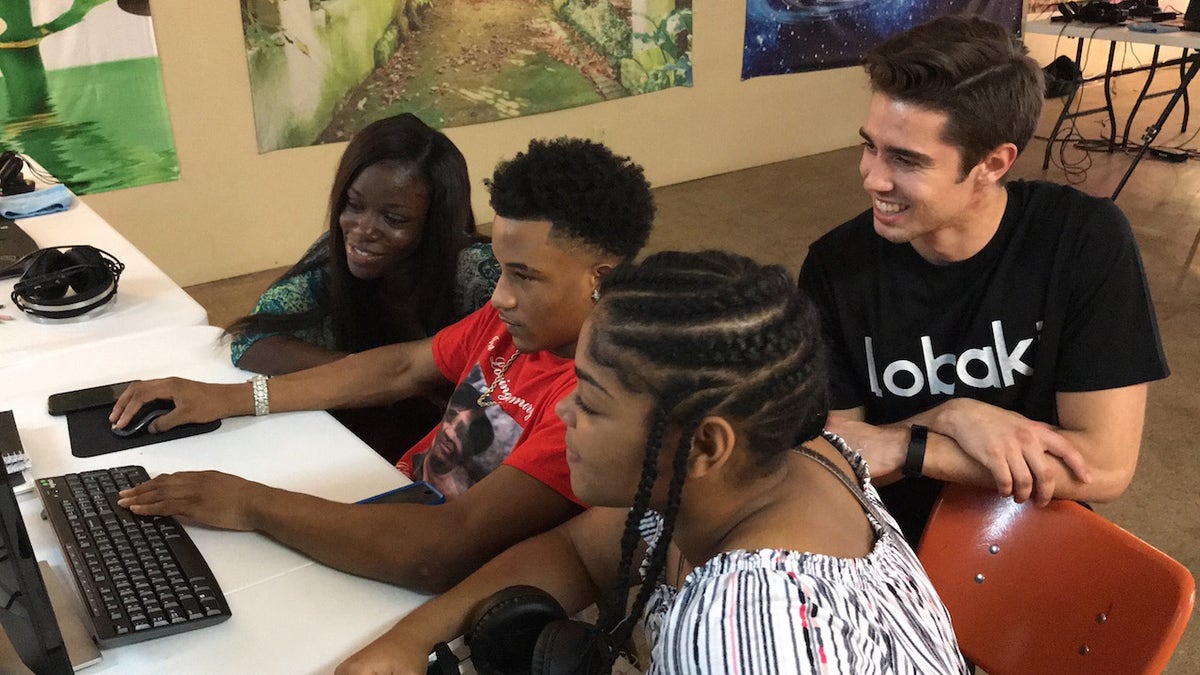

Michael Bezzina (rear) helps VR curators (left to right) Shalin Jewett, Deuntay Williams and Mya Calhoun edit at a workstation at Lobaki Inc. in Clarksdale, Miss. (Fox News)

The academy is able to host eight students at a time. The students themselves are able to work and get paid for their work while also learning on the job. The young VR curators have even created an original video game called “Fall Fear Fly Redemption,” which sells for 99 cents on the Steam video game platform. So far, it has raised a few thousand dollars for the academy and has been sold in at least 16 countries across the world.

Many of the teens working at the academy said their zip code and surroundings limit their success, but with a potential future career in VR on the horizon, many of them have changed their outlook on life.

“It make[s] me happy [waking] up in the morning time,” said Deuntay Williams, one of the standout VR curators in the academy. “When I used to pick cotton, I used to wake up [mad] that I got to go sweat…every second to make money and now I can just sit down and make video games and learn…and do what makes me happy.”

Williams and others at the academy have even started assisting young people in the state with their VR ambitions. Jordan noted how Lobaki helped set up a new ‘Extended Reality’ lab at Jackson Preparatory School (Jackson Prep), a grades 6-12 independent school in the Jackson, Mississippi, area.

Jackson Preparatory School near Jackson, Miss. recently added 26 advanced virtual reality stations that students will begin using when school begins in August. (Fox News)

With an estimated tuition of up to $14,700 a year, the school has resources that many areas in the state don’t have access to. High-end VR systems could cost thousands to purchase. Adam Mangana, the director of the virtual reality lab at Jackson Prep, said with the cost of VR headsets coming down, his hope is that many more schools gain access to the growing field.

“Our administration, who’s incredible, created the conditions for us to build the largest virtual reality lab in the Southeast, probably in the country,” Mangana said. “It really takes a team of kids to build an amazing experience and having kids engage and own their own learning is a really exciting phenomenon.”

Mangana has done extensive research on VR and is working on a capstone project focused on integrating the technology into education at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College.

With 26 VR stations, the students will be able to try different educational experiences such as visiting iconic sites using Google Earth, getting an in-depth look inside the human body, or having a lifelike experience as a sanitation worker in Memphis during the 1960s. The school ran a VR camp earlier this summer, shortly after purchasing the equipment. Some students, like incoming ninth grader Chambers Malouf, were well on their way to designing their own games with the help of Lobaki Inc. even before the school invested in the technology.

“That would be great, I mean if we could get other [schools] on board to get a VR lab and get younger coders and programmers,” Malouf told Fox News. “It would be revolutionary, not only for Mississippi but just in general for the next generation.”

When asked about video game addiction and a recent World Health Organization report about gaming disorder, Jordan, Mangana and school administrators at Jackson Prep said they believe VR as an educational tool will get kids more involved in school rather than fuel a gaming fixation.

Lobaki Inc. already has plans to open a VR lab at a technical school in Mississippi and the tech company is looking into Alabama, Indiana and Utah for sites in the near future to address the growing need for talent.