More media accolades for Colin Kaepernick's anthem protests

Fox News contributor Kevin Jackson sounds off on the NFL quarterback receiving Sports Illustrated's Muhammad Ali Legacy Award.

Amidst a national conversation about police brutality and athletes’ protests during the national anthem, organizers, students and victims of police violence will gather in Minneapolis not far from where Super Bowl LII is taking place.

A year and a half ago, St. Anthony, Minnesota police officer Jeronimo Yanez shot and killed Philando Castile in his car after pulling him over, sparking international outrage after Castile’s girlfriend livestreamed the incident and uploaded it to social media.

Not long after, former San Francisco 49ers quarterback began his protest against police brutality and racial injustice by first sitting, and then taking a knee, during the national anthem. His actions—praised by some and heavily criticized by others—eventually inspired other football players and athletes to also take a knee in solidarity.

As the NFL has faced flagging attendance and sagging ratings, and the protests during the national anthem have seemingly died down, many fans wonder if sports should be a politics-free zone.

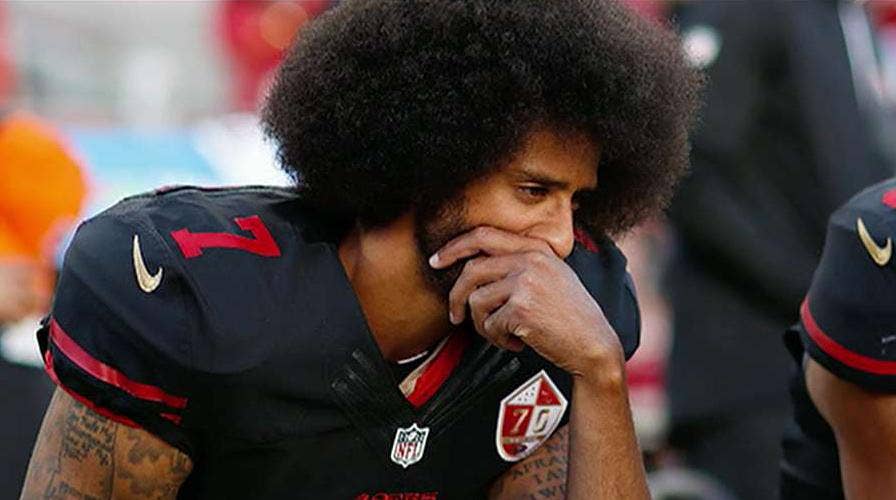

Former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick, who has not been signed by any team in the NFL, is seen here kneeling during the national anthem. (AP Photo)

However, the truth is that athletes, especially those in the African-American community, have been protesting against injustice for a long time. Kaepernick’s efforts are just the newest method in a practice that’s deeply embedded into American life.

“The whole purpose of the demonstrations is to get (fans’) attention,” Kareem Abdul-Jabbar said in an interview with The Associated Press. “These are the people that ignore the fact that people are being shot dead in the street. They’ve found ways to ignore it.”

MARINE CORPS' FIRST SUPER BOWL AD IN 30 YEARS TARGETS CORD-CUTTERS

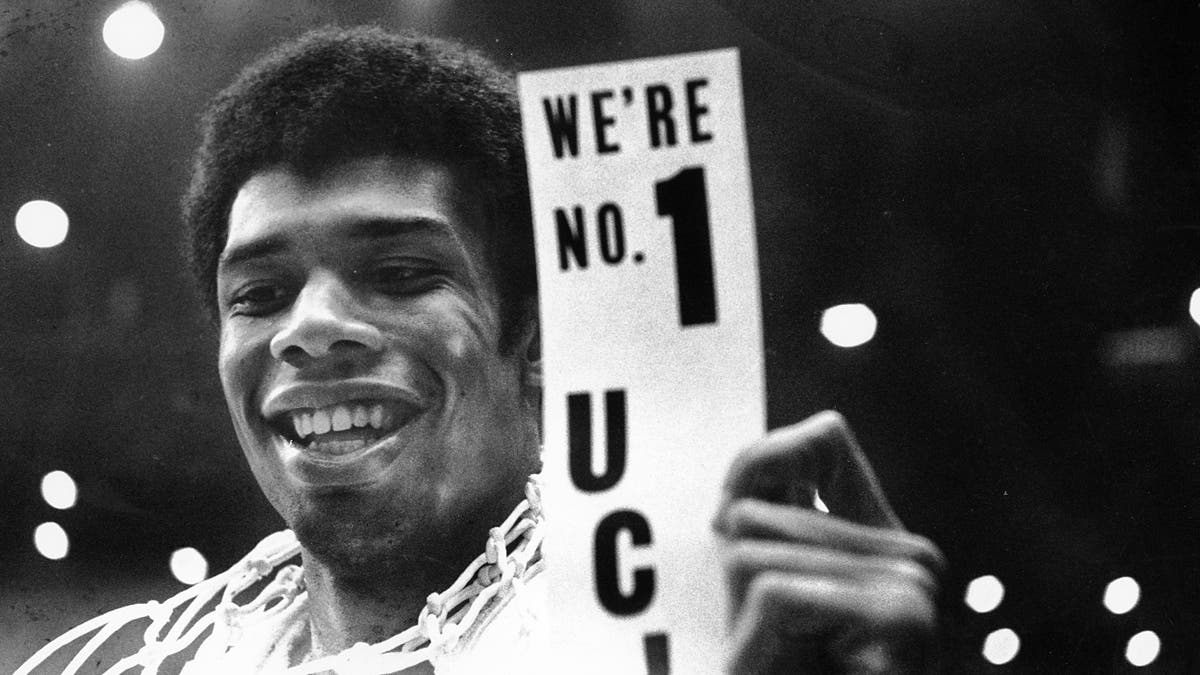

UCLA's Lew Alcindor holds a sign just after leading UCLA to the NCAA basketball championship in Los Angeles on March 23, 1968. Alcindor boycotted the 1968 Summer Olympics. After winning his first NBA championship in 1971, he took the Muslim name Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. (AP)

For generations, black athletes from heavyweight boxer Jack Johnson to tennis champions Venus and Serena Williams to Kaepernick have protested in ways large and small to highlight injustice, galvanize support and move the country forward. Often met with backlash from fans, many have taken stances that have cost them their careers.

The roots of black athlete activism can be traced to the dawn of black freedom. Even after slavery ended, black Americans were barred from full participation in the public sphere. Because they were blocked from entry in most civic institutions for much of the 20th century, black people found public visibility and expression in other arenas — often cultural ones, like music and sports.

Johnson fought — and beat — white boxers at the height of Jim Crow, when blacks were presumed to be inferior, and dated white women, upending the social norms of the day.

When he lost, it would be a generation before another black boxer would be allowed to compete at such a level, and the message had been sent to black athletes that disrupting society came with consequences.

The protests have prompted a range of responses from military veterans, some of whom don’t agree with Kaepernick’s method but respect his right to do so.

“I don’t feel [disrespected]. I just think they don’t know what they’re doing. … I feel sorry for them, because they don’t realize the luxuries and safety and freedoms they’re blessed with. That’s what the flag represents: everything they’re blessed with, the millions of dollars these guys have, all the luxuries they have. The flag represents that as well—it represents them,” Special Forces Green Beret sniper and medic Michael Rodriguez told Esquire.

Cleveland Cavaliers' LeBron James wears a T-shirt reading "I Can't Breathe," protesting the death of Eric Garner while being arrested by NYPD officers, warms up before an NBA basketball game against the Brooklyn Nets in New York. (AP)

SUPER BOWL LII: HOW TO WATCH AND WHAT TO KNOW

Jarrin Jackson, a former Army officer and Ranger who deployed with the 101st Airborne Division, told the Tennessean: “It doesn't bother (me) how people use their freedom.”

But, he also said, “People who kneel during the anthem (whether they know it or not) push an anti-America message.”

Participants in Sunday’s protest, scheduled to take place close to US Bank Stadium, claim that’s not the case.

“This never had anything to do with the flag or the national anthem,’’ said John Thompson, a scheduled speaker at the event. “They took [the kneeling protests] and made their own story out of it. I’ll be glad when someone gets it. You know how they say, for every action, there’s an equal, opposite reaction? Here it is.’’

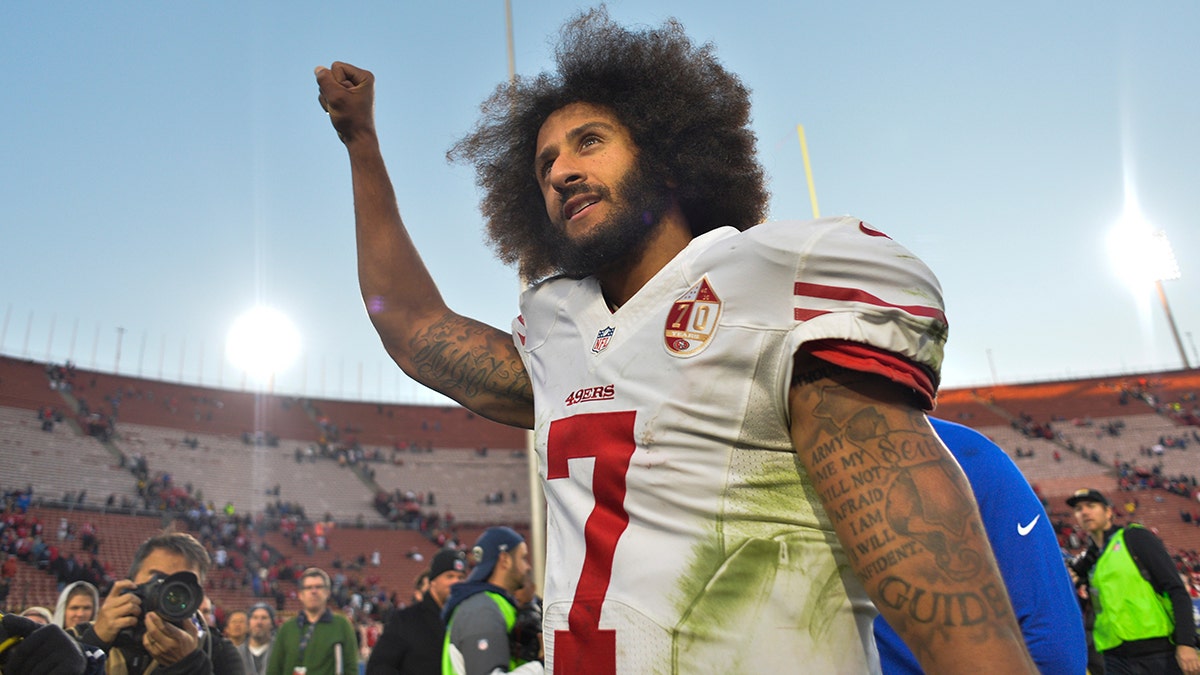

Former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick (7) pumps his fist as he acknowledges the cheers from the 49ers' fans after leading his team to a 22-21 come-from-behind win over the Los Angeles Rams in December 2016. (Reuters)

Looking back, Muhammad Ali was the most visible and influential athlete of his generation when he protested the Vietnam War as racially unjust by refusing to be drafted in 1967, a move that cost him his livelihood but also influenced the actions of others—including U.S. track athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos, and basketball player Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

“You’re not allowed to check out,” Howard Bryant, author of The Heritage: Black Athletes, A Divided America, and the Politics of Patriotism, told the Associated Press. “This is going to continue until the United States respects the black brain more than the black body. Then sports can go back to what it was supposed to be — just a game.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.