Taliban confession: Recruit recounts rape, blackmail

A Fox News exclusive interview reveals how the Taliban uses rape and blackmail to recruit many young terrorists against their will. WARNING: Contains material that may be offensive

EXCLUSIVE – KABUL, Afghanistan -- Tucked deep inside the compound of Afghanistan's paramount foreign and domestic intelligence agency is a detention facility that houses the country's most hardened accused terrorists. It's a quiet place of old pale buildings, few windows and layers upon layers of security.

Outside, a low-profile, gray Toyota Hilux pulls up and two freshly captured terrorists, blind-folded, are carefully pulled from the back of the pickup and led into their new confinement at the National Directorate of Security (NDS) facility.

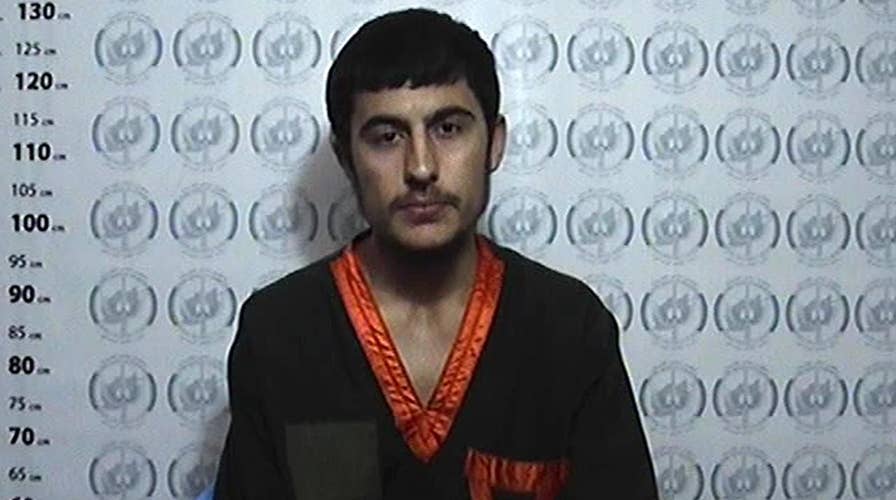

Inside, a young Taliban fighter is brought upstairs from the cell he shares with several others and led into a small, dimly lit ground floor room. Wearing his prison garb of black flip-flops and a deep green, orange-trimmed shalwar -- the traditional men's Afghan dress -- he sits down, appearing nervous. There are neither handcuffs nor blindfolds.

His name is Haibatullah, and like many Afghans only uses one name. He is 18 years old. Haibatullah agrees to speak to Fox News, of his own will, to detail his descent into the dark path of Taliban terrorism, which started when he was 17, some 10 months ago.

A friend, he says, convinced him to travel more than 300 miles from his home in the southeastern province of Ghazni to the Pakistan border city of Quetta, a city known to be a haven for Taliban members and one filled with people who support the group's hard-line ideology.

Haibatullah (Hollie McKay/Fox News)

"He said that the Americans and foreigners do whatever they want to our country," Haibatullah says, referring to his friend's "motivation" speech. "And we must fight the foreigners."

Once in the Quetta camp, which he refers to as the "secret brick camp," the indoctrination of hate only went deeper. For two months, Haibatullah was trained to use an array of guns and weapons and recite verses from the Quran to convince him that it was "mandatory to use jihad against foreigners" and "fight the infidels."

Haibatullah -- a timid, unshaven, almost child-like figure -- cowers a little more and suddenly announces that he has something to say. He buries his head in his hands and weeps silently. For long moments, nothing is said.

During training, a mullah told him to prepare to be a suicide bomber, but he refused on the grounds that he "was not ready." He says he was repeatedly told to engage in sexual acts with the mullah, but he continued to say no. Then one day after lunch, Haibatullah -- just 17 at the time -- claims that the mullah called him away. He woke up in a state of confusion and excruciating pain some time later, his legs covered in blood.

"After that," Haibatullah goes on, fidgeting and grief catching his voice. "He told me that he filmed the rape and if I didn't follow his orders and bomb myself, he would reveal the tape."

Haibatullah was raped two more times after that. The mullah, he says, called his parents and told them that their son was with the Taliban and because of that he had nowhere to go, nobody wanted him. Haibatullah suspects others also were drugged and raped, but he never said a word and nor did anyone else.

Taliban fighters react 2016 to a speech by their senior leader in the Shindand district of Herat province, Afghanistan. (The Associated Press)

According to a NDS official, who was present in the room during the detainee interview but requested to not be named, Haibatullah's story is almost certainly true and not unique. Drugging victims and filming rapes for blackmail has become a standard weapon of coercion used by Taliban leadership. Another high-ranking NDS official also pointed out that the mullahs generally separate the "most vulnerable minds" for such atrocities, and that they also are witnessing an increase in detainees who have been intravenously administered large amounts of human growth hormone.

After training and filled with silent shame, Haibatullah crossed freely back with others into Afghanistan, where he spent several more weeks in the eastern Laghman province, awaiting mission orders. The instruction came in November. Their target was the German Consulate in the northern province of Mazar-e-Sharif. They were told to kill, that only foreigners would be inside and that they must kill each and every one of those foreigners.

So Haibatullah and four Taliban comrades took a private car north to

Mazar-e-Sharif, believing it to be their last day on earth.

On the morning of Nov. 11 last year, one of his crew -- adorned with a suicide vest -- rammed a truck into the consulate. The blast overturned nearby cars, blew out shop windows and left a crater in the ground. The others, including Haibatullah, opened fire.

Of the assailants, Haibatullah alone survived. The attack remains something of a blurry horror movie. He remembers the chaos, the body parts, the burning building and the smell of smoke. He remembers running across the street, reeling with shock and fear of what he had just done. He remembers his head pounding with the sound of the "big bang" repeating over and over. He remembers walking a little way, unable to control his legs.

And then in the midst of it all, Haibatullah curled up on the hard ground and fell asleep. He doesn't know how long he slept, but when woke up he wasn't sure whether he was alive or dead.

Taliban chief Hakimullah Mehsud with Taliban fighters in 2009. (AP/File)

Then the shout of an NDS Special Forces soldier rang out, ordering him not to move. Haibatullah's "fight for freedom against foreigners" had just ended in handcuffs.

That attack left 20 civilians dead and more than 120 wounded. Although the target, no members of the German Consulate staff were injured.

While Haibatullah says he is still not sure whether having Americans and other NATO forces in Afghanistan is a "good or bad thing," he reiterates multiple times that one thing is for certain: His acts in Mazar-e-Sharif, the killing of his own countrymen, was a mistake.

"I am 100 percent regretful," he says.

The Taliban leaders did not pay Haibatullah or his cohorts a salary, but their expenses such as fuel and food were covered. Before carrying out the German Consulate attack, they were each given $50.

In his pre-Taliban life, Haibatullah had completed his education up until ninth grade and then joined his father selling vegetables at a local bazaar. He says no members of his family or extended family belonged to the Taliban or any associated group, and that they were a poor, yet proud, family.

"My father even used what money he had to enroll me in a private school," Haibatullah recalls.

He says he did not inform them that he was leaving for a jihadist camp, but once he had arrived in Quetta he called to say he was attending a madrassa to further his religious studies. His father cried with disappointment that he had abandoned his family.

Since Haibatullah's capture, his devastated parents have traveled to see him at the detention facility, yet those visitor moments are filled with dishonor and sadness. Nonetheless, he rejects the notion that he should be considered a terrorist.

Haibatullah is currently awaiting trial and will be moved to another detention facility after sentencing. Typically, notes an NDS official, terrorists found guilty receive anything from a 20-year sentence, to life behind bars, to execution, depending on their crimes.

"The Taliban are puppets of Pakistan. They are coming into Afghanistan to fight a proxy war and they are all bad people," Haibatullah says, looking around at the dirt-smeared walls and the bare sliver of afternoon sunlight from the small high window. "It is because of them, I am here."

His head low and flanked by guards, the detainee prepares to be led away.

"It is better I am here," Haibatullah adds. "Because if I ever see that mullah again, I will kill him."