(AP)

The first break came with the massive blizzard that wreaked havoc on the East Coast, essentially locking television viewers in their homes. The Daytona 500, meanwhile, was to be broadcast live in its entirety for the first time, reaching markets that knew little, if anything, about stock car racing. The 3 1/2-hour event finished in stunning fashion, another fortunate turn that featured a muddy, bloody brawl a few hundred yards from the finish line.

It was NASCAR's version of a perfect storm.

And it changed the sport forever.

FOOTBALL COULD BE COMING TO DAYTONA INTERNATIONAL SPEEDWAY

"It was just a storybook day," Hall of Fame driver Darrell Waltrip said. "It started off almost as a disaster, but it ended up like a big, old soap opera."

Thanks to a landmark television deal with CBS, a winter storm that stranded a large portion of the country and a spectacular ending involving several top drivers — including Richard Petty, Cale Yarborough and brothers Bobby and Donnie Allison — the 1979 Daytona 500 was instrumental in broadening racing's southern roots. Forty years later, it still resonates as perhaps the most pivotal race in NASCAR history.

"It was a wild time," Hall of Fame driver Bill Elliott said. "It was the talk of the town."

It was more like the talk of the nation.

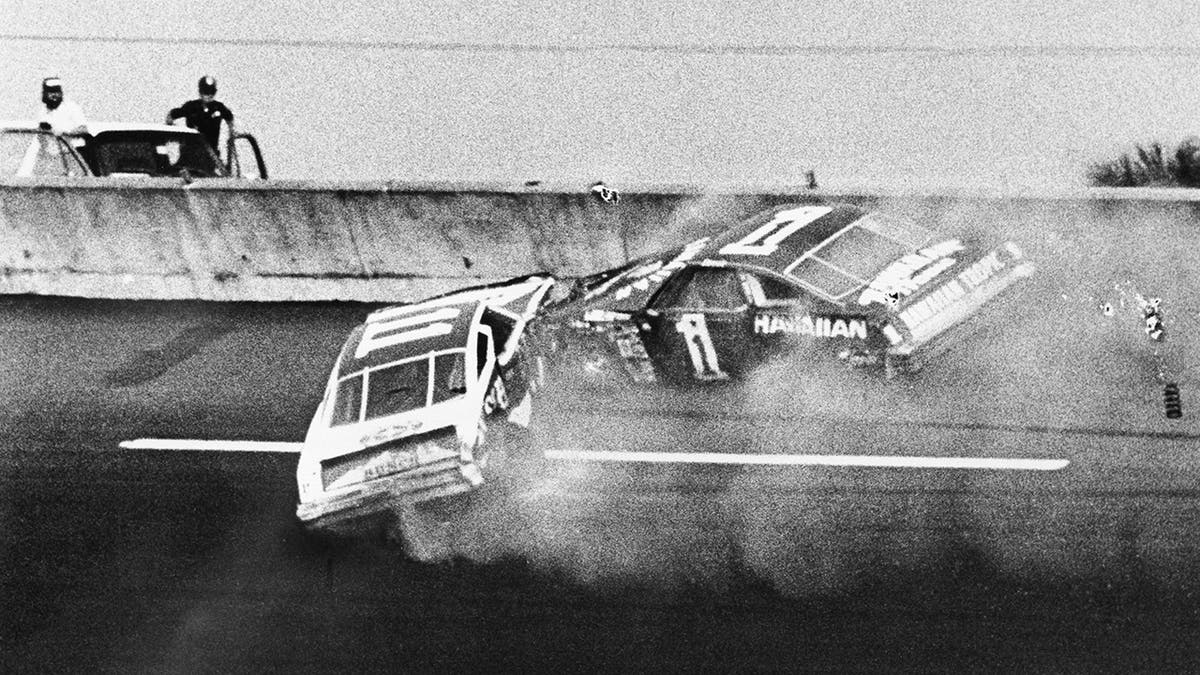

Donnie Allison, in car 1, and Cale Yarborough, in car 11, crashed on the last lap of the Daytona 500 to put Richard Petty in Victory Lane. (AP)

The chain of events started a year earlier, when NASCAR founder Bill France sent the effusive Waltrip and veteran commentator Ken Squier to convince TV executives that they needed to broadcast the race from start to finish. At the time, NASCAR's limited TV exposure would come from short, weekly segments on ABC's "Wide World of Sports."

France was convinced auto racing was poised for growth, ready to expand beyond the bible belt. TV executives weren't so sure anyone would care outside the southeast.

France and CBS eventually hashed out details and signed a contract in May 1978 to televise next year's 500 live for the first time. The logistics were a handful, with CBS installing 12 cameras around the 2 1/2-mile track and needing an immeasurable amount of cable to make them all work.

The setup was innovative, too. CBS placed one camera directly next to the track, so close to the action that the cameraman had to wear a motorcycle helmet for protection, and another inside a race car. Several drivers balked at mounting the 35-pound camera in the passenger's side, but Benny Parsons agreed.

Nonetheless, the biggest storm in more than a decade almost ruined all the planning.

Cities were essentially shut down. Roads were impassable. Millions of people ended up getting snowed in, and back then, they had just three network channels for entertainment.

In Daytona, it had rained overnight and again the morning of the race. The downpours eventually stopped, and the skies cleared. But the high-banked superspeedway was soaked, and NASCAR had nothing close to the drying technology it has today.

The race needed to go off on time to keep the TV contract intact, so France decided to start it under caution even though the racing surface was far from dry. The belief was 41 cars turning laps at half speed would get it dry enough to race.

Waltrip went out in front of the field for a test lap and radioed back to NASCAR officials that the track was good to go, so after 15 laps under caution, drivers took the green flag for the 21st running of the Daytona 500.

"Before that day, I think people looked at the sport as a bunch of guys having a good time on Sunday afternoon," Waltrip said. "They didn't know how serious or passionate the drivers were about racing and winning. I think it really opened a lot of people's eyes to what this sport was about. We never had a venue do that before."

The race had plenty of intrigue.

Pole-sitter Buddy Baker had early engine trouble and finished 40th. Three other favorites — the Allison brothers and Yarborough — got tangled up on the backstretch on Lap 31 and fell well behind the leaders.

Donnie Allison and Yarborough managed to get back to the front thanks to two of the fastest cars in the field. They were running 1-2 over the final 20-plus laps and had a 17-second lead over a three-car pack that included Petty, Waltrip and A.J. Foyt.

Yarborough waited until the last lap to make his move. He went low to pass Allison coming off Turn 2. Allison blocked him, forcing Yarborough into the backstretch grass. Yarborough's No. 11 Oldsmobile swerved out of control and moved back up the track and into Allison's No. 1 Oldsmobile. Both cars got loose at that point, slammed into each again, turned into the outside wall, slid back across the track and came to a halt in the muddy infield.

With Squire deftly handling play-by-play, he helped cameramen find the new leader, Petty.

"It turned out to be a wing-dinger," said Petty's crew chief, Dale Inman.

Petty held off Waltrip as they circled the final two turns and won his sixth 500, ending a 45-race winless streak four months removed from major stomach surgery. Petty's entire crew piled onto his iconic No. 43 for a ride to victory lane.

The fireworks were happening a few hundred yards away.

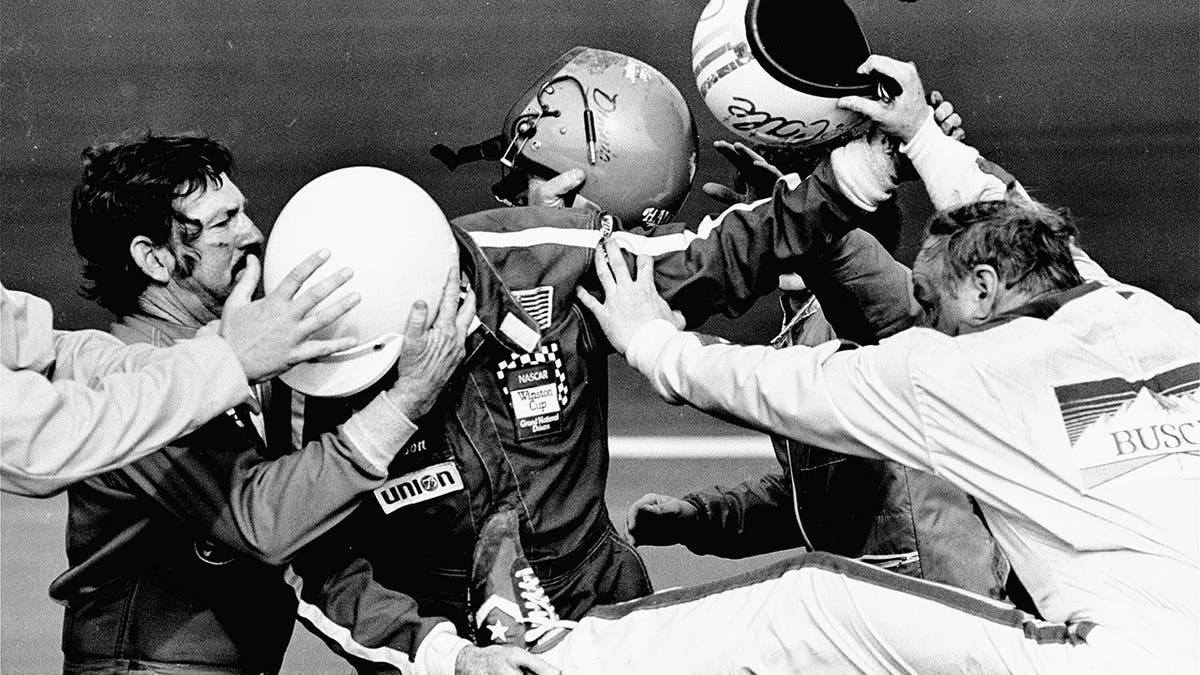

Bobby Allison had stopped his car near the crashed cars to see if Donnie needed a ride back to the garage. Yarborough confronted him through his window.

"He ran toward me and started yelling at me," Bobby said. "And then he hit me in the face with his helmet, which really surprised me. I still had my seatbelts on. I had my helmet on, and that shielded me a little bit, but it cut my nose and my lips.

"By then, blood was dripping in my lap. I've either got to get out of the car and handle this or run from him the rest of my life. So I got out of my car and he went to beating on my fists with his nose."

Yarborough and Allison tangled in the mud, with fists, helmets and feet flying all around. Donnie got involved late, but never threw a punch.

"It wasn't a good fight because I never hit the son of a gun," Donnie said. "I ought to have. There's no telling what I would have done to him. It would have been a real fight."

More than 15.1 million people watched the race and all its aftermath. It stood as the highest-rated NASCAR race until 2001. By then, the series hardly resembled the sport that took hold in the south. Sponsorships boomed. Drivers became household names and millionaires. NASCAR went from backwoods to boardrooms.

"It was one of the high points of NASCAR, put NASCAR on a nationwide map, OK?" Petty said. "Everything that you could put into a program, you had it that day. ... It couldn't have been a better footstep for NASCAR at that particular time."

Four decades later, 1979 Daytona 500 highlights get replayed as often as any race on TV.

Daytona recognizes its significance, too. A life-sized color picture of the fight adorns a wall inside the Turn 1 tunnel.

"It might not have been the way NASCAR wanted it to be, but sometimes things just kind of fall in your lap and you make the best of it," Elliott said. "It shaped and molded our sport. It's just part of the history, right, wrong or indifferent. There's no denying it."