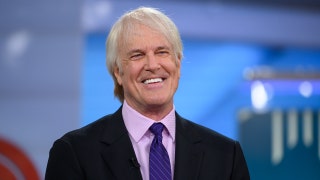

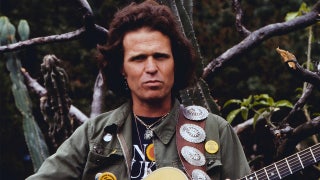

John Fogerty thinks he's one 'Fortunate Son'

FOX411: John Fogerty sat down with FOX411 to discuss his new memoir

NEW YORK – John Fogerty's memoir “Fortunate Son: My Life, My Music” (Little, Brown) hit the shelves on October 6. The book could very well have been titled “Fortitude, Son,” as the man who was the driving force behind one of America’s most beloved bands, Creedence Clearwater Revival, goes into stark detail about sticking to his principles and persevering in the face of great odds.

In his autobiography, Fogerty recounts how he had to power through the deep acrimony festering within Creedence as the band got more and more successful, how he weathered being sued for plagiarizing his own songwriting — a ludicrous notion eventually triumphed over in court — and the years he spent painstakingly learning new instruments in order to play every note himself on his 1985 comeback album, "Centerfield."

Fogerty sat down in the FOX411 studios on the day of the release of “Fortunate Son” to discuss his earliest memories of being a songwriter, his ongoing ties to the military, and how the big wheel that is “Proud Mary” first came to roll on the river.

FOX411: You mention early on in the book that you were aware of the concept of being a songwriter. How did that come about at such a young age?

John Fogerty: I was in preschool, I believe, and I might have even been 3-and-a-half. My mom was a teacher at the preschool, which is why this is all interrelated. One day, I came home from school, and she presented me with a little kid’s record. She played both sides, one song on each side. One side was “Oh! Susanna,” and the other side was “Camptown Races”… (sings), “Doo-dah, doo-dah!”

And then she explained to me that both of those songs were written by Stephen Foster. I took that in just the way a kid would, and, in my 3-and-a-half-year-old psyche, I thought Stephen Foster was in there somehow, singing on the record.

To me, what’s most fascinating now, as I look over my life, was she was telling me about the songwriter. I just think that’s so remarkable. Usually with a kid, you play him a Christmas song like “Jingle Bells” or “Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer,” and you’ll talk about the story, but not about the songwriter.

FOX411: In the fall of 1967, you got yourself a vinyl notebook, and the very first phrase you wrote down in it became one of your most important songs, “Proud Mary.” Can you tell me how that came about?

Fogerty: Yeah. When I got out of the Army in 1967, I had determined, with more resolve, to get more organized than I had been previously in my life. Usually, you’d find an old napkin or a piece of paper lying around, and jot down something whenever the mood would strike. I was pretty careless about it all.

Then I thought, “You need a place where you can keep all these ideas.” I went to a store, got a little vinyl notebook, and waited around for something to happen. Within a few days, the phrase “Proud Mary” came to me. I wrote it in the book — it’s the very first entry on the first line. I didn’t know what it meant. I didn’t have a clue what “Proud Mary” was, but I put it in my book.

A few months later, after I’d written several more things in the book, I was in the midst of an inspiration. It turned out to be a song about a boat and the Mississippi River. I looked in my notebook, and there was “Proud Mary.” “That’s the name of the boat — Proud Mary!” And it all came together.

FOX411: I happen to think, as a songwriter, you’re one of the best editors out there. You often said to yourself, “How do I make this better?” as one of your impetuses to write a better song.

Fogerty: Well, thank you. I’m certainly aware of that, and I take pride with my better songs that I worked on them. Perhaps it was because of my mom talking about songwriters when I was a little kid. She would talk about Irving Berlin or Hoagy Carmichael, who was still around when I was little, so I knew Hoagy’s songs and some of the stories behind them. I read several books about different writers and somewhat how they worked, and I accepted that premise that you don’t just go on inspiration, and that’s that. You continue to polish your song and try to make it better.

I know that flies in the face of a lot of the rock & roll ethic, but I had grown up with the idea that a great song was a worthy thing. It doesn’t just happen casually. It’s a thing you’re proud of. And probably the most particular thing to me, at least, was the idea of being concise. Try to say whatever it is you’re trying to say, but use the best words, and the fewest words. Because, number one, it leaves room there to tell more stuff, you know? (smiles) I like that idea. I don’t like being very, very wordy in a song. I like the idea of, if you find a really great word, the listener will have room for his imagination to take over.

FOX411: I’d say you’re a master of both the short form and the long form, in a way like John Updike, Philip Roth, and John Cheever could all write both really good short stories and long stories. You had those concise, 2- or 3- minute songs on those two-sided singles that went to the top of the charts, but you were also able to do these 7- or 8-minute epics like “Suzie Q” and “Keep on Chooglin’.” How were you able to balance those two things?

Fogerty: Well, it’s funny. I think there was the influence of what was going on in San Francisco in the mid-to-late-’60s — The Grateful Dead, Quicksilver [Messenger Service], Jefferson Airplane — the idea of extended songs, and jamming. I myself went to a few concerts in San Francisco. There were always things in Golden Gate Park, at Winterland, or the Fillmore. Even though I had grown up listening to what you’d call commercial music, meaning Top 40 radio, where the songs of Elvis and The Beatles were all 2-minute gems, I was also intrigued with the idea of what we now call jamming.

The concept of stretching out was really intriguing and fun. I did like that too. I think I wanted to pick my spots, you know, with what songs to treat that way.

FOX411: Tell me about the bond you continue to feel with the military.

Fogerty: Well, I was a kid growing up in the mid-’60s of draft age and the Vietnam War was heating up, so that whole event was a great big shadow or cloud over America, and certainly the whole culture of the ’60s experience.

I would have preferred at the time that I didn’t get drafted and I hoped I wouldn’t be, but like so many other guys my age, I got myself into an Army Reserve. So happily — for me, at least — I didn’t have to go overseas to Vietnam.

All of us dreaded the idea that we could be sent at any time into the jungle. In fact, whenever you messed up, your superior would go, “You want me to send you to Vietnam?” — the catch-all phrase to get everybody in line, because they had that power. And then you’d be gone.

I lived through that at the same age as many of the people who were serving in Vietnam. At first, it was subliminally. I learned what that was all about — I mean the mindset, not the combat and the horrible situations in the jungle. I realized that I was with all of those guys emotionally and mentally, the way everybody felt. And once you were in the military, there’s a certain way — because you’re a Private, you’re the lowest form of life on the earth and the universe, so you get used to how you are treated and how you are talked to, whatever your grievances may or may not be.

And that really influenced me. It was something I lived through. When I was out of the military and started writing songs and having an attitude about the way things were being done in America at that point in time, a lot of this experience started coming out in my music. I had an insight that helped illustrate the song better. Being on the outside, I’m sure you could write a valid song, but having been in the military, I had certainly felt that dread that all of us did at the time. It informed what I did. It gave it a point of view that may have been different, had I just been a civilian.

FOX411: “Fortunate Son” sure feels as relevant today as when you wrote it in 1969.

Fogerty: I was just trying to write a good song that told a story. I wasn’t self-aware. And it wasn’t until a long, long time later that I realized: I really nailed it, you know? It’s very concise and very pure. Each little part of it is for a purpose, talking about that dread — and the inequality of class, of course, which inspired the whole thing in the first place.

FOX411: A lot of people feel “Run Through the Jungle” was written about Vietnam, but you say in the book it’s a song about gun control. How do you feel about that today, especially in the light of recent events?

Fogerty: “Run Through the Jungle” was really inspired by the proliferation of guns in American society, even though the song was mistakenly thought to be a Vietnam jungle song. This was way back in 1970, and I felt uneasy about it. I was worried about it. I felt it was a problem. As time has gone on, I feel more that way.

The reality of weaponry is scary to me, and every time we have something like what we had recently [at Umpqua Community College in Roseburg, Oregon], everyone thinks about it a lot more.

The subject is complicated, and very emotional for a lot of folks. I’m a hunter, and it was kind of the same experience I had with the military — being a hunter, being around others who hunt and others who have guns, you’re not an outsider talking about it. You learn from the inside. I believe in the right to bear arms. The solution — which we don’t have yet — is going to be very tricky to come to, but we do need to have some kind of psychological testing.

FOX411: Finally, I see that you’re an advisor on this season of The Voice. What is your best advice for somebody starting in the music business today?

Fogerty: Follow your dream. Find out what it is you’re really good at, and don’t let anybody talk you out of it.