Jonestown cult survivor recalls horrifying massacre

In a new A&E documentary, Leslie Wagner-Wilson tells the story of how she survived the deadly Jonestown cult.

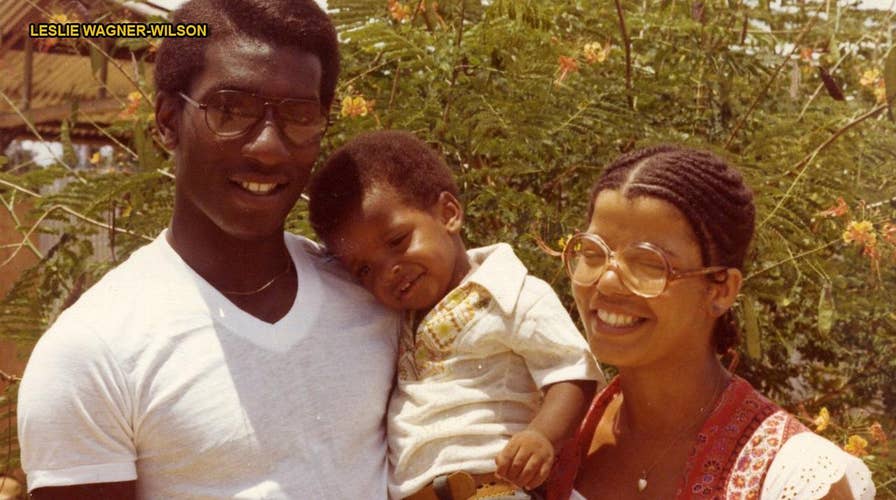

Leslie Wagner-Wilson escaped death at age 22 when she strapped her 3-year-old son, Jakari, to her back and trekked over 30 miles through the jungles of Guyana with nine others.

On Nov. 18, 1978, Jim Jones, the leader of the People's Temple, had ordered the deaths of 918 followers by cyanide poisoning; 304 of them were children. Wilson lost six of her family members.

Jones, the leader of the religious movement, was found dead from a gunshot wound to the head at 47.

The Arizona-based grandmother is now coming forward to share her story for a new documentary on A&E, titled “Jonestown: The Women Behind the Massacre,” which examines the influence that four women in the cult leader’s inner circle had on the infamous mass murder and suicide ritual.

Sundance TV has also greenlit a docuseries that will air this November to coincide with the 40th anniversary of the tragedy with Oscar-winning actor Leonardo DiCaprio serving as executive producer.

Wilson hopes her participation in the A&E documentary will shed new light on a catastrophe that, prior to the 9/11 terrorist attacks, marked the single largest loss of U.S. civilian lives in a non-natural disaster.

“I think Peoples Temple rose from a social/political environment that’s similar to what we’re facing now,” Wilson told Fox News. “There’s a need. People want to be a part of something. They want to feel safe, they want to feel a sense of community… I want Jonestown to be a lesson… There are still folks out there and they are running under the guise of religious organizations. I just want people to be careful.”

Wilson described a happy childhood in San Francisco filled with summer camps and vacations. However, things changed when she turned 13. (Courtesy Leslie Wagner-Wilson)

Wilson can still vividly remember life before Jonestown. She described a happy childhood in San Francisco filled with summer camps and vacations. However, things changed when she turned 13.

“This was the late ‘60s, during the love and peace movement,” she said. “A lot of drugs, which my sister Michelle became involved in. Acid, LSD… My mother was told by a friend about an organization, People's Temple, that had a great drug rehab program. That’s how we got involved.”

Jones, a charismatic preacher, first opened the People's Temple in the mid-1950s in Indianapolis. By the early ‘70s, Jones and his wife relocated their headquarters to San Francisco, and his popularity grew. Jones’ message of social justice and a racially integrated congregation attracted a diverse group of followers, many of them African-American.

Wilson was proud to become a part of the community.

“I felt like I was going to make a difference in the world,” said Wilson. “I didn’t know children were going to bed hungry, people were being jailed or there was racism or discrimination [in the world]… I felt really compelled… to just be a young girl who would be active on social issues. And I loved it, I really did.”

But by 15, Wilson was starting to have doubts about Jones’ message.

“I think he was so insecure that he would always tout his sexual prowess and talk about how men were homosexuals,” she said. “He treated the women better because the women were more loyal… But also, he was very manipulative and would try to separate families and destroy marriages, which would give him more power… [And] we thought Jim could read our minds so I would stay away. We would say, ‘Don’t ever say anything negative when he passes us because he can read our minds.’ We were totally fooled in a lot of ways… It just became very controlling. It wasn’t fun anymore.”

Wilson hopes the documentary will show audiences Jones had enablers to help him lead a cult and that her personal journey will warn people that similar groups still exist. (Courtesy Leslie Wagner-Wilson)

Jones, who is said to have believed he was the only heterosexual on the planet, had sexual relationships with several of his female followers. He also became increasingly addicted to pharmaceutical drugs.

“In San Francisco, he would say that he’s tired because he stayed up all night doing all of this good work,” recalled Wilson. “We didn’t know about the drug use… But towards the end, there were times when he never came out of his house. You can hear him slurring his words, but he would just make up excuses, say he was tired or wasn’t feeling well. The community had no idea, even in San Francisco, that he was abusing drugs. That was new to me after the suicide massacre.”

Wilson wasn’t the only one to have doubts. In the ‘70s, news media were beginning to investigate claims of abuse and tyranny, prompting Jones to summon his followers to Jonestown, his sanctuary in Guyana. However, it was far from a utopia.

“It was tough,” she explained. “We had outhouses. We didn’t have flushing toilets… Cold showers were OK because it was so humid and hot. But, I went in with an open mind and tried to find the positive in that. I felt that this was a community where we could make a difference… We were hopeful. We were optimistic that we could build something that was incredible. And with that comes some sacrifice.”

But death awaited Wilson if she stayed. A day before the massacre, Congressman Leo Ryan and several newsmen had come to investigate the remote settlement, only to be shot dead by Jones’ followers. And prior to the massacre, Jones reportedly ordered “revolutionary suicide” rehearsals.

“It just became a place where there was no future,” she said. “I had a child… We were basically starving. We were eating rice every day. No vegetables. No nutrients. It just became obvious this place was a prison… I was ready to go. And if Jim had given people the option to go, I think there would have been a lot of people who were ready to get back to the states… But we had no voice. And that didn’t change in Jonestown.”

Wilson fled in secret with her son.

“I feel grateful every day because I did not believe I was going to live past the age of 22,” she said. “I had to forgive Jim Jones and those involved in order for me to move on and live. I have two other children. I have grandchildren. I have a good life.”

Wilson hopes the documentary will show audiences Jones had enablers to help him lead a cult and that her personal journey will warn people that similar groups still exist.

“I cannot believe there weren’t people like myself whose mind first said there’s something wrong, but because everyone else is embracing it and clapping and being joyous, you look at yourself and say, ‘It must be me,’” she said. “It’s important we don’t see this again in this magnitude.”