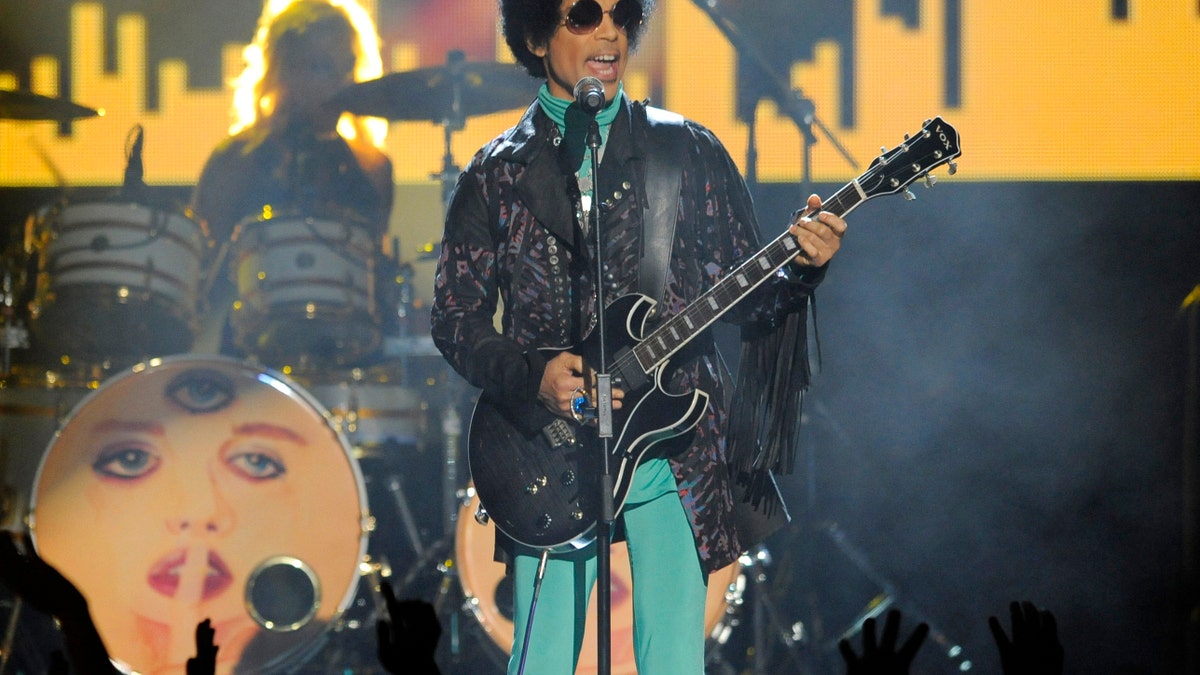

FILE - In this May 19, 2013, file photo, Prince performs at the Billboard Music Awards at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas. More than five months after Princeâs fatal drug overdose, investigators have narrowed their focus to two tracks: whether doctors illegally prescribed opioids meant for the pop star and whether he obtained the fentanyl that killed him from a black-market source, a law enforcement official said. (Photo by Chris Pizzello/Invision/AP, File)

As the investigation into Prince's death homes in on the source of the fatal fentanyl, some observers are suggesting that the United States explore a lifesaving strategy used in Europe: services that check addicts' drug supplies to see if they are safe.

In Spain, the Netherlands and a handful of other countries, users voluntarily turn in drug samples for chemical analysis and are alerted if dangerous additives are found. The pragmatic approach saves lives, proponents say.

Increasingly, users of street drugs don't know what they're taking, according to U.S. law enforcement experts and treatment providers. Black-market suppliers are using cheaper chemicals to increase profits.

Cocaine may be mixed with the veterinary de-wormer levamisole, which can cause a painful, gruesome rash. Ecstasy may be a sometimes-deadly impostor called PMMA. White powder sold as heroin or pills stamped to look like prescription drugs may actually be the more potent fentanyl.

It's unclear how Prince got the fentanyl that killed him or whether he thought it was a less potent drug. Lookalike pills discovered by investigators in Prince's home were stamped "Watson 385" to mimic a common generic painkiller similar to Vicodin, an official close to the investigation told The Associated Press in August. On analysis, the pills were found to contain the more potent fentanyl.

Here's a closer look at the drug-checking services that proponents believe could have prevented Prince's death:

___

WHAT IS DRUG CHECKING?

It's an approach to overdose prevention that began in the Netherlands in the early 1990s. The effort expanded to Spain, Switzerland, Austria, Belgium and Portugal. Some of the programs receive government money.

Researchers who studied six years of data from the European programs found that the Netherlands and Spain — the nations with the most extensive drug-checking services — tended to have the highest purity of drugs, presumably because dealers and manufacturers knew consumers were testing their products. Public warnings about dangerous ingredients resulted in adulterated drugs disappearing from the street.

In July, an independent music festival in England called Secret Garden Party became the first United Kingdom event to offer attendees the chance to get their illegal drugs tested. According to the Guardian news site, samples tested included anti-malaria tablets sold as ketamine.

The effort was a project of a group called the Loop, which also uses the prevention slogan "Crush, Dab, Wait" — a recommendation to festivalgoers using MDMA, also known as ecstasy, to crush it into a powder, consume a small amount and wait one to two hours. If the drug is a potent fake, users would avoid taking a dangerous amount.

___

COULD IT WORK IN THE U.S.?

Drug-checking services could help government and public health agencies track emerging drug trends, said Traci Green, deputy director of the Injury Prevention Center at Boston Medical Center, who co-authored a recent commentary in JAMA Internal Medicine on fentanyl counterfeits and drug checking.

"You can't regulate black markets," Green said. "But we can try to make them safer and reduce the risk of death and harm."

Drug checking in the United States exists on a small scale and with a time lag. EcstasyData.org invites users to send pills or powders to a Drug Enforcement Administration-registered lab for analysis. Fees range from $40 to $150, in bitcoin or cash for anonymity. Results are eventually published online, sometimes with notes like "Careful!"

Recently, a New Yorker sent in a crystal called Moon Rocks, which was sold as MDMA. It was actually a chemical called N-Ethylpentylone. A pill — sold as oxycodone, sent in from Portland, Oregon — was actually fentanyl.

DEA spokesman Rusty Payne said the lab EcstasyData uses is approved to receive controlled substances from law enforcement, but "anyone who is receiving drugs from random people, whether samples or trafficker amounts, they're breaking the law and run the risk of arrest and prosecution."

A U.S. company called Bunk Police sells at-home test kits. Founder Adam Auctor said his kits could have detected fentanyl in the counterfeit pills at Prince's Paisley Park.

"These kits were available to the public six months prior to Prince's untimely death," said Auctor, who uses a pseudonym in his business to protect himself from disgruntled drug dealers and because someday he wants to start another company unsullied by illicit drugs. He said he is working with Barcelona-based Energy Control to offer drug-checking services.

___

COULD IT WORK WITH FENTANYL?

Michael Gilbert is a Boston-based consultant who monitors dark-web drug markets where he's seen "Watson 385" pills for sale only rarely. Sometimes, he said, mock pharmaceuticals are advertised by dark-web sellers as containing fentanyl, sometimes not.

Authentic "Watson 385" pills would contain mostly acetaminophen (brand name Tylenol) and only a small amount of the opioid hydrocodone, making them unappealing to most opioid users, Gilbert said. He speculated a "Watson 385" buyer might know the pill actually contained fentanyl.

"In a case like Prince, if somebody is buying drugs on the black market, they would do well to confirm they are purchasing what they intend to purchase," Gilbert said. "In the context of rampant counterfeiting, that's really important."

In Illinois, the Cook County Medical Examiner's Office has seen a surge in deaths attributed to fentanyl and its derivatives. But Dr. Adam Rubinstein, an addiction specialist at Advocate Condell Medical Center in suburban Chicago, said he doubts that drug-checking services would prevent fentanyl overdoses.

Heroin users aren't deterred by fentanyl's lethality, he said. Instead, they're attracted.

Rubinstein asked a 22-year-old patient, a young suburban woman who is actively using heroin, whether she or anyone she knew would use an anonymous drug-checking service to avoid fentanyl.

"She couldn't conceive of a person who would want that knowledge," Rubinstein said. "She said she too would actually seek out something laced with fentanyl that had caused death."