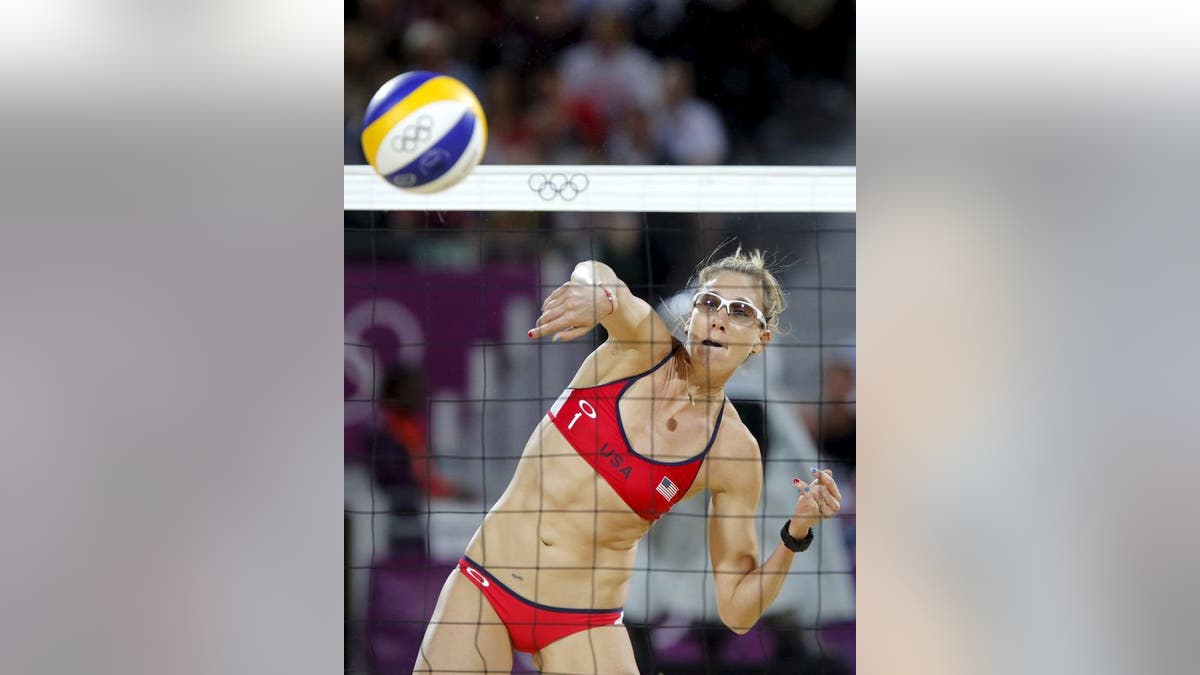

File picture shows Kerri Walsh Jennings of the U.S. spiking the ball at the women's beach volleyball gold medal match during the London 2012 Olympic Games (Copyright Reuters 2016)

LOS ANGELES – Few women have competed in the Olympics while pregnant, but the suspicion that the Zika virus in mothers is causing birth defects is central to calculations by athletes and others planning travel to Brazil in August for the summer games.

Chief among their concerns is whether Zika, unlike similar mosquito-borne viruses, can be transmitted sexually, or remain latent in the body - possibly presenting a risk for women who become pregnant after the Olympics have ended.

More than a dozen disease experts, in interviews with Reuters, said there is no evidence at this point of long-term risk for future pregnancies. But, given the surprises seen with the virus so far, they said people should remain cautious until studies give scientists a better picture of how the virus works. They said it would take months or even years of study for definitive answers to questions about Zika's risks.

Public health agencies have urged pregnant women to avoid travel to Zika outbreak areas but have given little guidance for couples planning to start a family.

Dr. Claire Panosian, of the University of California, Los Angeles, division of infectious diseases, said that for years she has advised couples to wait several months after traveling to exotic locales before trying to conceive because of the risk of birth defects from diseases like toxoplasmosis.

Zika should be no different, she said: "Women of child-bearing age should be very scrupulous - wait several months."

The virus, which is spreading rapidly through the Americas, has been linked to a spike in microcephaly, a rare birth defect, in Brazil. The condition is defined by unusually small heads in newborns and can cause brain damage.

Zika has not been proven to cause microcephaly, but evidence of an association led the World Health Organization to declare the outbreak a global health emergency.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says pregnant women should consider skipping the 2016 Olympics because of the risk of Zika infection. For women who are considering becoming pregnant - and their male partners - the agency recommends consulting their physicians in deciding whether to go to the Games.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, however, has suggested a more detailed time frame. It called this week for a six-month delay in all human cell or tissue donations, including of semen and eggs, from people who have had Zika infections or traveled to an outbreak area.

Canada's national health agency on Wednesday advised women who want to get pregnant to wait at least two months after traveling to countries affected by the Zika outbreak.

Eighteen women have competed in modern Olympics while pregnant according to a group of Olympic historians who publish their statistics at Sports-Reference.com. The number includes U.S. beach volleyball gold medalist Kerri Walsh, who was not yet aware she was pregnant when competing in London in 2012.

Some current Olympic hopefuls say they might think twice about the Rio Games if Zika could threaten future pregnancies, and they are hoping for some better answers before the competition begins.

"If things stood as they are right now, I probably would not go," renowned U.S. soccer goalkeeper Hope Solo told CBS last week. "At some point I do want to start a family, and I don't want to be worried."

Solo has spoken out about feeling conflicted over her two great ambitions - winning Olympic gold and becoming a mother in the future. "It's scary, and I have a lot of reservations about going to the Olympics," she said.

DeeDee Trotter, a 33-year-old Olympic sprinter and medalist who aims to make the U.S. team again this year, said in an interview she wasn't worried "if the only danger is to women who are pregnant."

That sentiment could change if a prior Zika infection is shown to pose a risk later "when I do decide to have children," she said.

The U.S. Olympic Committee has told athletes that babies may be at risk if the mother is infected with Zika while pregnant, or if she becomes pregnant within an unknown time frame after being infected.

"We have worked to ensure that all potential Olympic and Paralympic athletes are aware of the CDC's recommendations, and we will continue to do so," USOC spokesman Mark Jones said in an emailed statement. "They are the experts."

THE IMMUNITY QUESTION

The CDC says experiencing a Zika infection once likely protects a person from future infection, although that immunity - like so many aspects of Zika - is not yet proven.

"It is likely that, following infection, people are immune, but what percentage of convalesced patients and for how long will not be clear for some time," said Dr. Leslie Lobel, chair of the department of virology and developmental genetics at Israel's Ben-Gurion University of the Negev who has been working with Ugandan and Brazilian scientists to investigate Zika.

Whether the virus can remain in the body and cause a recurrence also is not known. In one case, Zika virus was detected in semen 62 days after the man was infected, but it was not clear whether it was capable of infecting someone else.

Separately, the CDC is investigating at least 14 cases of possible sexual transmission.

Zika was first identified in 1947 in Uganda and previously linked to smaller outbreaks. Many people who are infected show no symptoms, while those who become ill report relatively mild effects of rash or fever. There is no vaccine or treatment for the virus, which is in the same family as dengue, West Nile virus and yellow fever.

Ann Powers, acting chief of the arboviral disease branch at the CDC's Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, said other viruses similar to Zika do not remain latent in the body. But she said it will take months or years to know for certain whether Zika behaves similarly.

Viral infections provoke the human immune system to eliminate the invader, leaving behind "memory cells" to fight future incursions by the same virus. But some viruses, like HIV or herpes, can stay in the body, leaving a person vulnerable to repeat flare ups. Others, like dengue, can infect multiple times because they have several strains.

"My feeling is that Zika is very close to dengue virus," said Jae Jung, director of the University of Southern California Institute for Emerging Pathogens and Immune Diseases. "There is probably a very, very low chance of latency" - or a propensity for recurrence.

Other experts caution that Zika's apparently unique behavior on many fronts means that nothing should be taken for granted.

The deadly Ebola virus, from a different family, has not provided immunity to all patients who survived infection. In several cases, including a Scottish nurse, the virus appears to have been reactivated many months after recovery.

"We cannot assume based upon yellow fever and dengue what's going to happen with Zika. This one's different," said Dr. Joseph Vinetz, a tropical disease clinician and professor at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine.