WHO member warns of 'additional pandemics' if we don't learn from COVID

Former World Health Organization expert committee member Jamie Metzl joins 'America's Newsroom' after the Biden White House missed the Sunday deadline to declassify documents on the origin of COVID-19.

The skeletons of people who were alive during the 1918 flu pandemic have revealed new clues about people who were more likely to die from the virus.

Known as the deadliest in history, the 1918 flu pandemic — also referred to as the Spanish flu — killed an estimated 50 million people.

It’s long been assumed that the 1918 flu primarily affected young, healthy adults — but a new study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences seems to contradict that, suggesting that frail or unhealthy people were more vulnerable.

DOCTORS URGE VACCINATIONS AHEAD OF THIS YEAR'S FLU SEASON, WHICH COULD BE 'FAIRLY BAD,' EXPERTS SAY

Researchers from McMaster University in Canada and the University of Colorado Boulder examined the skeletal remains of 369 individuals housed at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

All of these individuals died either soon before or during the 1918 pandemic, according to a press release from McMaster. The sample was divided into two groups: a control group who had died before the pandemic; and another group who died during the pandemic, according to the release.

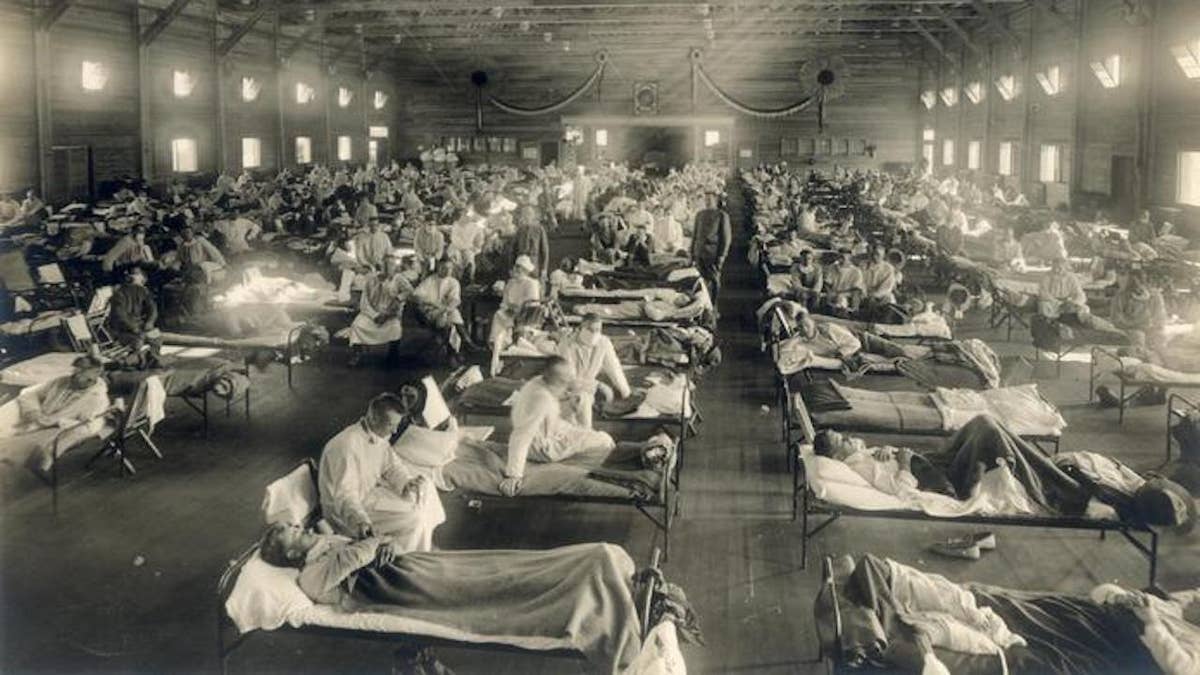

An emergency hospital at Camp Funston, Kansas, is shown during the 1918 influenza pandemic. New research contradicts the widespread belief that the flu disproportionately impacted healthy young adults. (National Museum of Health and Medicine, Otis Historical Archives New Contributed Photo Collection/Wikimedia Commons)

They examined the bones for lesions that would have indicated stress or inflammation, which could have been caused by physical trauma, infection or malnutrition, the release stated.

"By comparing who had lesions, and whether these lesions were active or healing at the time of death, we get a picture of what we call frailty, or who is more likely to die," said Sharon DeWitte, a biological anthropologist at the University of Colorado Boulder and co-author on the study.

"Our study shows that people with these active lesions are the most frail."

FLU PREVENTION TIPS FROM FLORIDA'S SURGEON GENERAL: A 'DAY-TO-DAY’ HEALTHY LIFESTYLE IS KEY

Lead study author Amanda Wissler, an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at McMaster, said the study highlights how cultural, social and biological circumstances affect the likelihood of death.

"Even in a novel pandemic — one to which no one is supposed to have prior immunity — certain people are at a greater risk of getting sick and dying, and this is often shaped by culture," she said in an interview with Fox News Digital.

A demonstration is shown at the Red Cross Emergency Ambulance Station in Washington, D.C., during the influenza pandemic of 1918. (Getty Images)

The researcher noted that this same phenomenon was seen during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S.

"The news was full of reports about how people who had been minoritized, or [had] decreased access to social services, often had greater rates of getting very sick or dying," she said.

"‘Healthy’ people are not supposed to die. We have a term called ‘selective mortality,’ which says that certain people are more likely to die than others."

The findings of the study were not surprising to the researchers, Wissler said.

"‘Healthy’ people are not supposed to die," she said. "We have a term called ‘selective mortality,’ which says that certain people are more likely to die than others."

COVID-19 PATIENTS FACE INCREASED HEALTH RISKS FOR UP TO 2 YEARS, STUDY FINDS

"Many studies have found that certain people are more likely to die in all kinds of contexts, including other pandemics like the Black Death, and also in natural disasters," the researcher continued.

"I would actually have been somewhat surprised if people who were healthy had a greater risk of death in 1918."

Study had some limitations

One key limitation of the study, according to Wissler, is that the researchers only had information on people who died from the pandemic — but none on people who got infected but survived.

"We don’t know if being unhealthy or stressed may have caused a person to be more likely to [have been] infected with the 1918 flu," she said.

A demonstration is shown at the Red Cross Emergency Ambulance Station in Washington, D.C., during the influenza pandemic of 1918. (Getty Images)

Additionally, the individuals who were studied all came from Cleveland, Ohio, Wissler noted.

"This study only provides a snapshot of a certain time and place of the experience of the 1918 flu," she said.

"We don’t know yet if what we found here can be generalized to every city."

COVID-19, FLU AND RSV VACCINES ARE ALL AVAILABLE THIS FALL: SEE WHAT SOME DOCTORS RECOMMEND AND WHY

MarkAlain Déry, DO, an infectious disease physician in New Orleans, noted that the study raises some questions. He was not involved in the research.

Initially, Déry said he was "super excited" about the new research, which highlighted "that people who experience health inequities have higher rates of illness and mortality."

To protect against today’s strains of influenza, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that everyone 6 months and older get an annual vaccination. (Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

The research is "more or less saying what we already know, which is that people in vulnerable communities and in lower socioeconomic statuses have a greater level of frailty and mortality as a result of the 1918 influenza outbreak," Déry said.

The key issue, however, is that it’s not known whether the people who were examined died of influenza, he pointed out.

Also, the size of the study was relatively small, he said.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

Overall, the researchers noted that the project highlights the importance of studying the past.

"Studying past pandemics and epidemics provides us with a time depth to our understanding of how these diseases affect humans and how we, in turn, affect diseases," Wissler told Fox News Digital.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

"A lot of the time, we find that the risk factors for disease that we have today were the same in the past."

To protect against today’s strains of influenza, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that everyone 6 months and older get an annual vaccination.