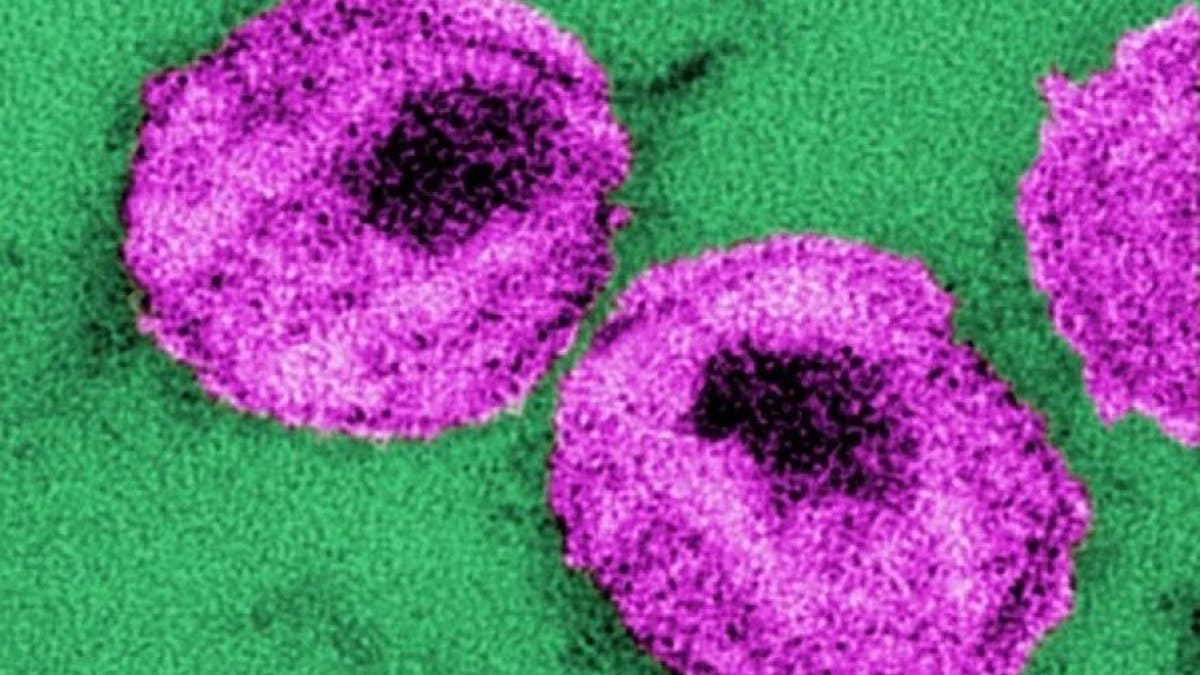

Early treatment of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can dramatically reduce the odds of passing the deadly disease on to others, and the protection persists for years, according to final results from a major study that looked at the timing of antiretroviral therapy, or ART.

The findings were presented at the International AIDS Conference in Durban, South Africa and published online by the New England Journal of Medicine.

Early therapy for HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, "was associated with a 93% lower risk of linked partner infection than was delayed ART," reported the team, led by Dr. Myron Cohen at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

"If you take antiretroviral therapy to the point of (virus) suppression, there's a vanishingly small risk you will infect your partner," he told Reuters Health in a telephone interview. Among 1,763 volunteers, "We saw no transmissions when people successfully took their treatment" and it was given time to work.

However, when volunteers were allowed to delay therapy until they developed an AIDS-defining illness or their CD4+ cell counts fell below 250 cells per cubic millimeter, the odds of infecting someone increased dramatically.

AIDS-defining illnesses include certain infections and cancers. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a list online, at http://bit.ly/29OB5dy.

People with HIV infection who feel well often delay treatment, which increases the risk. It can take up to three months to bring viral levels low enough to make the person no longer infectious, Dr. Cohen said.

There are more than 2 million new cases of HIV worldwide each year.

The new study, conducted in nine countries, used genetic tests to see which new infections were likely linked to each other.

Half the couples in the study were tracked for at least five and a half years. During that time, 78 partners developed an HIV infection. Genetic testing was done in 72 of those cases.

Among the people who received early antiretroviral therapy, there were only three cases where the partner developed a genetically identical HIV infection. There were 43 such cases in the delayed therapy group.

"They had more time to have sex with their partner when they weren't getting ART," Dr. Cohen said.

There were 26 cases were the partners developed HIV and the strain was not a genetic match, so the partner had become infected from another source. Fourteen cases involved the partners of people who were in the early treatment group and 12 cases involved the partners of people whose therapy was delayed.

Early results released in May 2011 resulted in the recommendation that all HIV-positive patients receive early ART.

But even when all the volunteers were offered treatment, 17 percent had decided one year later to not take the drugs because they felt healthy, their CD4+ cell counts - which indicate how far the infection has progressed - remained high or they were concerned about the risk of side effects.

"The point of getting these results out is to change the culture for the doctor and the patient so they realize the enormous benefit for immediate treatment," Dr. Cohen said.

In 2015, early ART therapy was recommended by the World Health Organization.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases funded the study, known as HPTN 052.