Fox News Flash top headlines for September 1

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

A mother raising awareness of a dangerous challenge – arguably popularized by social media – has dedicated her life to ensuring another parent won’t feel the same pain of losing their child — as she did more than a decade ago.

Erik Robinson was a Boy Scout who played on a Little League team and very much enjoyed school. The 12-year-old had military dreams and was already in talks with the admissions department at West Point, mom Judy Rogg, of Santa Monica, California, told Fox News.

"Erik was very energetic, very active, very smart, very perceptive," Rogg said. "He earned his privileges…he had responsibilities and understood them."

Rogg said her son was independent, not a people-pleaser and "very judicious about who he wanted to be friends with."

"He was not one to be bullied," she added. "He was not one to be forced into doing things he didn’t want to do."

MOM WARNS AGAINST FIREWORKS AFTER ONE EXPLODES AND ‘BLEW' HER HAND IN HALF

Rogg said that on April 20, 2010, Erik arrived home and started his homework.

Not long after, it appeared Erik had left his workspace to try what’s known as a "choking game," among many other terms. Erik used a rope tied to a pull-up bar in the doorway between the living room and the dining room, according to his mother.

Judy Rogg and her late son Erik Robinson, 12, are pictured in March 2010. (Courtesy of Judy Rogg)

Rogg said she found Erik unresponsive and took him to the hospital, where he spent 24 hours on life support before she and his father made the difficult decision to disconnect him.

At the hospital, police told Rogg her son's death was likely caused by the "choking game" — in which the goal is to restrict cerebral blood flow to the point of nearly or actually passing out for a variety of reasons including curiosity, competition, being dared or wanting to experience an altered state.

Rogg has since founded the organization Erik’s Cause, which aims to bring awareness of deadly "pass-out activities," such as the "choking game" into the national spotlight "so parents and children understand its true dangers and lives can be saved."

US FAMILIES ADOPTING AFGHAN CHILDREN ARE TRYING TO GET THEM OUT OF THE COUNTRY

"I said, ‘We knew it wasn’t suicide, but you guys are crazy?,’" Rogg recalled in her response to police. "He’s too smart to do something that stupid."

Rogg said one physical sign separating "pass out activities" from suicide is if the child participating is "connected to the floor," meaning kneeling, sitting or standing.

According to Rogg, there are several ways kids participate in hazardous "pass out activities" aside from using a ligature, the "deadliest" method by far."

Some kids will record the act and post the video on social media. Based on her data collection through Erik’s Cause, Rogg has found that the most common age range for children participating in "pass-out activities" is between 9 and 16.

'There was nothing on any of our computers'

Dr. David Diamond, a cognitive neuroscientist and psychology professor at the University of South Florida, broke down the science behind why young people may participate in these dangerous challenges.

"It’s not stupidity, it’s that children and teens have partially formed brains," Diamond told Fox News.

"It’s a capacity to look to the future — that’s really what the frontal cortex does and that’s what preteens lack, an appreciation for the consequence of their actions," he added.

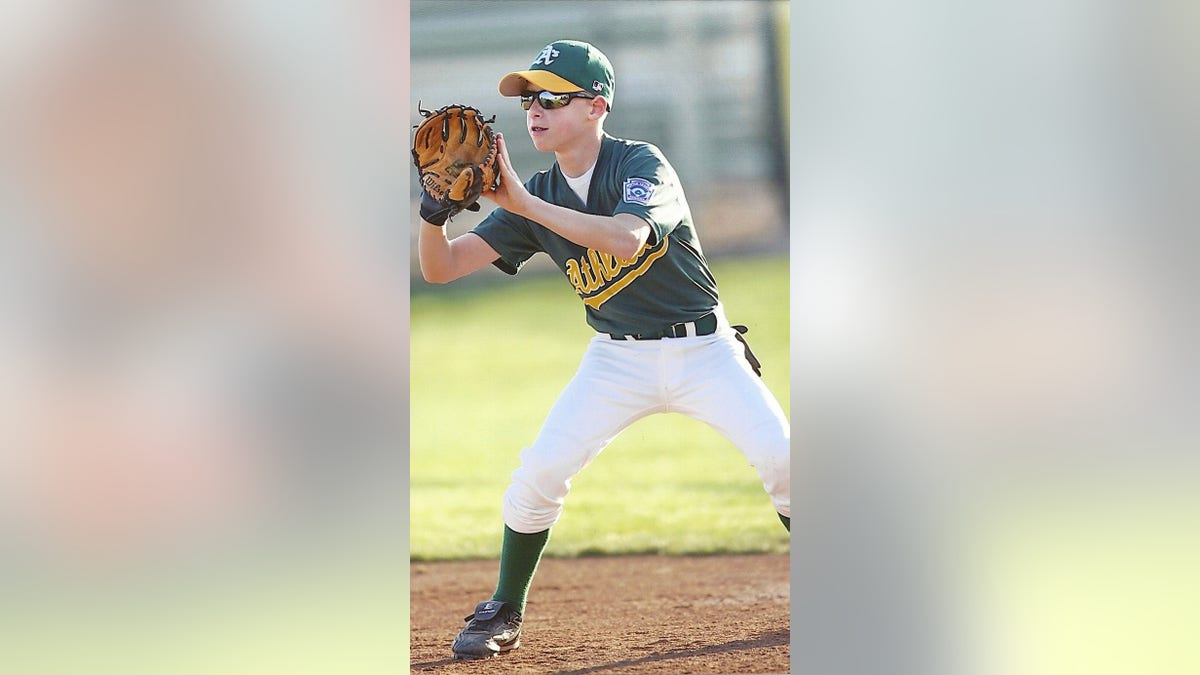

Erik Robinson is pictured playing baseball in 2010. (Courtesy of Judy Rogg)

Rogg said that over the years she’s avoided talking too much about the painful details of Erik’s death, but right away, she knew it wasn’t suicide.

She explained that Erik had earned an award during a Boy Scout retreat the weekend before his death and it was clear, according to her, from where she found him, that he didn’t think he was going to hurt himself.

Rogg said it’s also significant that Erik didn’t try the "game" in a closet or in his bedroom, which shows that he didn’t think it would be serious.

"He was fully intending to go back to his work," Rogg said. "He wasn’t hiding."

COVID-INFECTED MOM DELIVERS PREMATURE CHILD, NEARLY DIES: ‘PROTECT YOURSELF AND YOUR BABY’

While news outlets have reported these "games" spreading on social media and video sites, Rogg said she had no evidence her son had seen any video online and nothing was found on her family’s computers. Rogg was told that Erik was seen the day before his death in the schoolyard talking about "choking games," she said.

"That doesn’t diminish the amount of it that’s all over the internet by any stretch of the imagination," she said.

Immediately after her son’s death, Rogg publicly called it a "tragic accident" and avoided addressing the "choking game."

"It's not stupidity, it’s that children and teens have partially formed brains."

She changed her mind after a reporter reached out to ask if Erik had died by suicide after being cyberbullied, which reportedly had happened to several other children at the time.

Rogg later decided to launch Erik’s Cause after she and a licensed marriage and family therapist developed non-graphic educational materials about the dangers of "choking games" that could be presented to children and teenagers in schools.

Some dangerous videos still accessible on internet, Fox News finds

Though Erik apparently didn’t learn about the game from the internet, videos of such "challenges" are pervasive across social media and have been for years, which make children and teenagers believe they are safe to try, Rogg said.

On April 10, 2021, a 12-year-old boy from Aurora, Colo., was placed on life support for 19 days after his family believed he had participated in the "blackout challenge," Fox News reported five days after the boy’s death. "Blackout challenge" videos had been circulating on social media platforms, daring users to choke themselves until they lost consciousness.

The family said at the time it was not clear exactly which social media platform the 12-year-old was using when he found the "challenge."

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Fox News searched several social media sites for results on choking and pass out "games."

No search results for the term "blackout challenge" appeared on the video-sharing app TikTok, which has risen in popularity online. However, Rogg pointed out that there’s a lengthy list for alternative terms which coincide with choking or passing out. A Fox News search of those other terms turned up five TikTok videos dating from 2019 and 2020 which appeared to be game incidents.

TikTok responded to Fox News’ request for additional comment on those videos, saying they’ve since been removed.

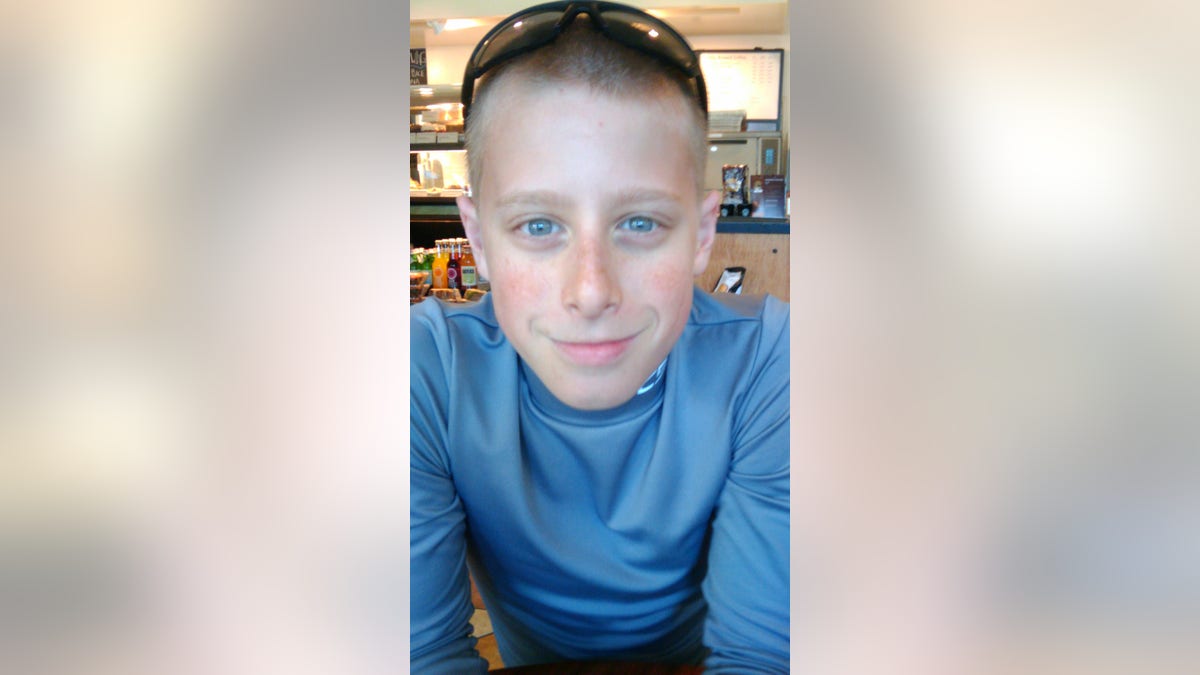

Erik Robinson is pictured in 2008. (Courtesy of Judy Rogg)

"We take the safety of our community very seriously and strictly prohibit dangerous challenges on TikTok. While we have not seen such content gain popularity on our platform, we remain alert and take action against any violative content if found," the TikTok spokesperson said.

The spokesperson also released a statement to Fox News regarding the "blackout challenge," and how the search term is blocked on its site.

"Protecting minors is critically important, and TikTok takes the safety of our community very seriously," the spokesperson said. "We strictly prohibit dangerous challenges on TikTok, and while we have not yet found evidence of a 'blackout challenge', we remain alert and ready to act against any violative content posted."

The spokesperson pointed out how the challenge would violate its Community Guidelines.

The spokesperson offered additional resources including How TikTok counters dangerous behavior and the TikTok's Guardian's Guide.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR LIFESTYLE NEWSLETTER

Back in July, over 12,000 parents signed a petition from family advocacy group ParentsTogether, which asked TikTok CEO Vanessa Pappas to allow parents to access their children’s accounts via mirror accounts so they could better monitor what they’re watching.

Dalia Hashad, the director of online safety at ParentsTogether, told Fox News that even though TikTok encouraged parents to "observe, very strictly, what children are doing on social media," Hashad said it’s all "impossible" without mirror accounts, because of the way algorithms work, adding, "the parents are not seeing what the kids see."

TikTok told Fox News it’s partnered with leading youth safety organizations, including the Family Online Safety Institute, ConnectSafely, the National PTA, the Digital Well-being Lab at Boston Children's Hospital and many others.

"We are deeply committed to the safety of our community, particularly our younger users. TikTok has taken industry-first steps to protect teens and promote age-appropriate experiences, including strong default privacy settings for minors; Family Pairing so parents can directly manage their teen's account; and age restrictions on messaging, livestream, and more," the spokesperson said.

TikTok also offered its latest work to advance safety and privacy for minors on its platform.

Erik Robinson is pictured playing baseball in 2009. (Courtesy of Judy Rogg)

In a search on YouTube, Fox News found videos describing how to faint or pass out. The videos were dated 2011, 2014, 2016 and 2020.

YouTube has not yet responded to Fox News’ request for comment regarding the videos.

"It’s kind of Whack-a-Mole," Rogg said. "If you take one down, 15 more are going to go up."

Reporting from other news outlets has addressed how similar asphyxiation "challenges" or "games" appeared prior to the launch of TikTok and all social media.

Incidents reportedly begin in 1930’s, though data remains foggy

Rogg said she’s aware that similar choking injuries and deaths predated social media, and that her aunt told her incidents occurred when she was a child in the 1930s. Rogg said that through her research, she’s learned that many of these deaths are often misclassified as suicides.

One of the most cited studies, Rogg pointed out, was released in 2008 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which reported evidence that children have died from choking "games" as early as 1995.

Rogg said the report "has severe limitations," which researchers admitted in the editorial notes. For one, the study relied on media reports found through a research platform which didn’t include all newspapers or local television news reports.

Even if all media reports were tracked, the study would still risk "low sensitivity and specificity," because outlets don’t report every accidental death and some newspapers could report a cause of death differently than what is written on the death certificate, according to the study’s notes. In addition, the news usually did not provide information on "the role of influence by peers or the media/Internet."

"It's kind of Whack-a-Mole. If you take one [video] down, 15 more are going to go up."

Though the CDC report found at least 82 deaths from the "choking game" from 1995 to 2007, Rogg said: "We know there are way more deaths than this."

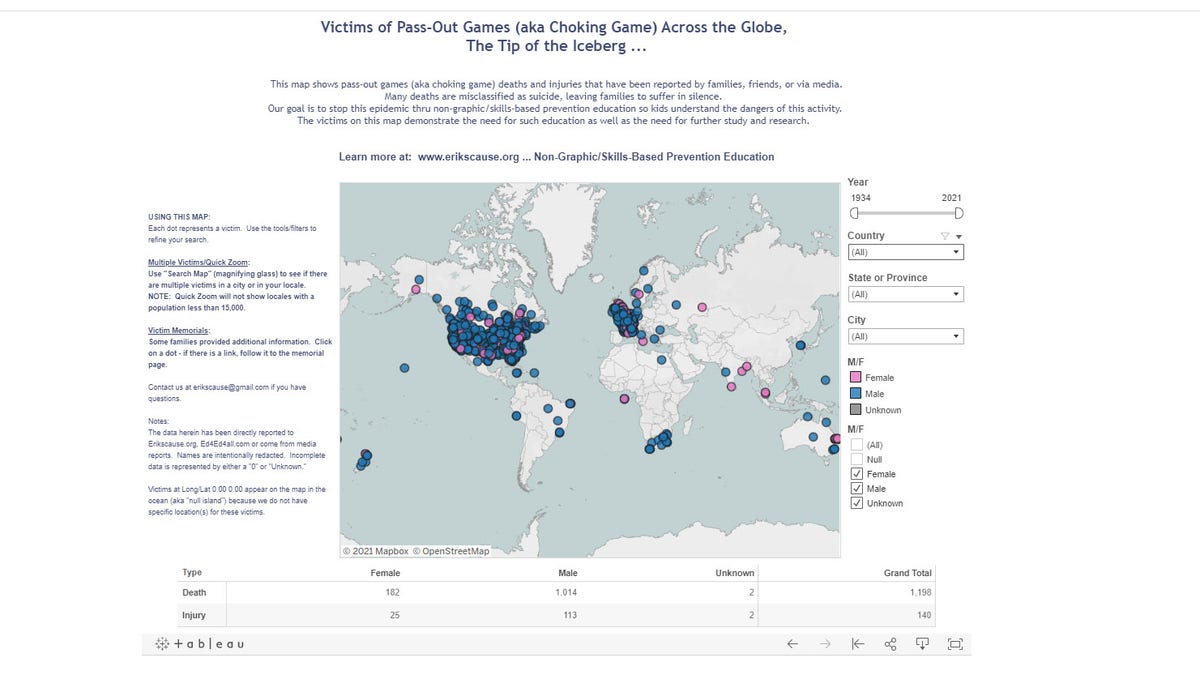

Through her work with Erik’s Cause, Rogg has launched a global, interactive victim map dating back to 1935, pinpointing any incidents of injury or death related to the "blackout challenge."

FOLLOW US ON FACEBOOK FOR MORE FOX LIFESTYLE NEWS

From 1935 to 1985, there were 18 U.S. deaths and three injuries recorded on the map. From 1985 to 2021 there were 764 deaths and 106 injuries. These incidents are significantly higher among young males when compared to females.

Rogg said she’s obtained data for her map from trusted news sources – only "a tip of the iceberg" – and from parents reaching out to her through Erik’s Cause after their children died from participating in pass-out activities.

Erik Robinson is pictured. (Courtesy of Judy Rogg)

According to her interactive map, Rogg also has received data from a nonprofit called Education for Educators, which has focused on educating young people about these "activities."

"It’s anecdotal," Rogg said. "There’s no other way to do it… because we don’t have access to death records," unless parents provided such records to Rogg.

Another challenge in collecting data: Many of these deaths are misclassified as suicide because the subjects are found with a ligature, Rogg said. Without further psychological investigation, many medical examiners and coroners determine the child or teen intended to take his or her own life.

"I try to do what I can," Rogg said. "It’s only as good as people reporting to us."

There is no national collection of data on pass-out activities, Rogg said. However, the CDC’s WONDER (Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiological Research) mortality database did keep track of unintentional/accidental strangulation deaths in the U.S. from 1999 through 2019.

After searching WONDER, Fox News found that 1,048 children between the ages of 9 and 19 died from "unintentional or accidental strangulation" deaths from 1999 to 2019.

A screengrab of the global Interactive Victim Map on the Erik's Cause website. (Courtesy of Judy Rogg/Erik's Cause)

Though it is "impossible" to say whether all those deaths were caused by pass-out "activities," Rogg said it’s a "likely assumption" that at least some of the children were participating in some kind of "game."

The youngest person to have died from a "pass-out activity" was 6 years old in Los Angeles County, Rogg said, adding that some people have died in their 20s.

One entry on the interactive map indicated that a 28-year-old man in Canyon County, Calif., died in 2011 from participating in a "pass-out game."

From 2008 to 2021, when social media rose in popularity, there were 374 deaths and 64 injuries in the U.S. alone. Worldwide, that number has grown to 521 deaths and 80 injuries.

MOTHER OF CHILD KILLED AFTER VISITING ICE CREAM TRUCK SPEAKS OUT AS SHE FIGHTS TO PASS SAFETY LAWS

"There's one part of the brain extremely sensitive to lack of oxygen – the hippocampus. When it is harmed by a lack of oxygen, it may remain damaged for life."

As for the common age range being between 9 and 16, according to Rogg, Diamond said the desire for pleasure can sometimes be toxic when combined with an absence of the "brakes on the instinctual system" – that being the underdeveloped frontal cortex, which doesn’t fully develop until late teens or early 20s.

"If you don’t have a well-developed frontal cortex, then an individual is more likely to seek out pleasure and not think about the consequences of their actions," Diamond said. "That defines the behavior of an adolescent and teen."

He continued, "When you think of this blackout challenge, what you have, in a sense, is a perfect storm in what goes wrong for preteens and teens. It’s a thrill-seeking, dopamine-seeking pleasure. In thrill seekers, they are looking to increase their pleasure neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, without sufficient inhibition on these thrill-based neurochemicals. The thrill satisfies the need to release pleasure hormones and neurochemicals."

Kids may experience dizziness from the lack of blood and oxygen. Afterwards: lightheadedness from blood rushing back to the brain, according to the Training Institute on Strangulation Prevention. Since they don’t know when they’re actually going to faint, kids will black out resulting in accidental asphyxiation, Erik’s Cause wrote on its website.

Erik Robinson is pictured in March 2010. (Courtesy of Judy Rogg)

Diamond said going just a few minutes without oxygen to the brain can cause serious and sometimes permanent damage, if not death.

"There’s one part of the brain extremely sensitive to lack of oxygen: the hippocampus," Diamond said. "When it is harmed by a lack of oxygen, it may remain damaged for life."

Diamond said doing the blackout challenge may cause a "cognitive deficit" and if someone survives the asphyxiation, the person may be forever unable to make new memories.

"It’s almost as if they would be transformed into someone who has Alzheimer’s," he explained.

Preventing more tragedies

Dr. Stephanie Samar, the director of the child and preadolescent dialectical behavior therapy program and a clinical psychologist in the Mood Disorders Center at the Child Mind Institute, spoke with Fox News about social media’s influence on impressionable children.

"Kids are [also] thinking too heavily about what others think," Samar said. "It’s extreme thinking too. You’re either good or bad, or you’re left out of a group."

Samar said that sometimes, kids’ online worlds can be so big and influential, that they could distance themselves from family, friends and overall support system.

"Those are the main themes we see that come with social media that we find very problematic," she added.

Samar offered tips for parents on creating a culture around conversation and getting kids to open up about what they’re seeing online.

Follow their lead

If your child is isolating more with social media and technology, talk to the child. "[Say], I’m curious. What are you doing on there?" Samar suggested, adding that rather than directing, give kids the opportunity to speak.

"The more you present with curiosity and remove judgment, the more you’re getting out of your teen as to why they’re interested in this," Samar said.

"The shame of thinking that you missed something in your kid is horrendous."

Understand social media means something different to them

Try to keep an open mind when kids talk about social media use. Learning why it’s important to them is vital to keeping that line of communication open.

Compare social media with reality

Remind kids how on social media, not everything is what it seems, and face-to-face relationships are different.

"A deeper understanding of the way it’s presented and the videos they’re seeing aren’t necessarily reality," Samar said, "because [kids] don’t have that depth, and are quick in their judgments."

Set rules for device use, and model that same behavior

Block out certain times a day for device use within common spaces at home. Talk about balancing the use of tech [even for yourself], having online friends and monitoring it as well.

One strategy Diamond suggested: Talking with children in an age-appropriate way about news stories on these "games" gone wrong can help them learn vicariously.

"Try to expose them as much as possible to see what happens to others when they don’t appreciate the consequences of something that’s hazardous," he said. "Teaching them about how this kind of thrill seeking can cause brain damage and can even cause you to die."

Erik Robinson is pictured in February 2010. (Courtesy of Judy Rogg)

Erik’s legacy making a difference

When asked what she misses about her son, Rogg said, "everything."

"Erik had an incredible love for life...I got to really enjoy that piece of him that just wanted to try and experiment and was caring and loving about people," Rogg added. "And he had a crazy wit, just sarcastic as hell."

"He was just so smart, so beyond his years in so many ways, but yet classically a kid."

In 2014, the Iron County School District in Utah formally adopted the Erik’s Cause prevention training program in its health classes for 5th, 7th and 10th graders.

Since the district started teaching the program to students, Erik’s Cause has surveyed the district’s students and found that their curiosity to attempt the "choking game" has decreased as they’re educated about the effects.

Rogg also has run a private support group for families who’ve had children die from attempting pass out "activities."

Because the deaths are often misclassified as suicides, Rogg said many parents experience "enormous grief" thinking they missed the signs in their child. That’s why Rogg’s support group, she said, has been important: so families could grieve together.

"So many parents don’t come forward," Rogg said. "The shame of thinking that you missed something in your kid is horrendous. And the truth is, you didn’t miss anything, except you didn’t know about this."

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255). You can also contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741.