1619 Project Founder says parents should not have a say on their children's education

Former professor Dr. Carol Swain slams Nikole Hannah-Jones for her statement that parents should not have a say in education

The New York Times Magazine's publication of the 1619 Project in August 2019 has helped spark a bevy of think pieces on critical race theory and paved the way for a surge in race-based reporting, multiple experts and analysts agreed.

The project, penned in part by lead writer Nikole Hannah-Jones, purports that 1619, the year the first enslaved Africans were brought to what would later become the United States, should be considered the true founding year of the country. Critics and historians who were consulted on the project have since hit the report as being full of historical inaccuracies, such as suggesting the Revolutionary War was fought in part to preserve slavery.

THE NEW YORK TIMES JOURNEY FROM PAPER OF RECORD TO HOME OF THE 1619 PROJECT

No matter what side of the debate Americans found themselves on, many noted the uptick in race-based studies and news reports.

The Washington Post published a database in January on the number of congressmen who once owned slaves. The authors declared their research provides a "greater understanding" of how slaveholding "influenced early America."

"More than 1,800 congressmen once enslaved Black people. This is who they were, and how they shaped the nation," the title of the study read.

Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones signs books for her supporters before taking the stage to discuss her new book, (Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

"The Washington Post has compiled the first database of slaveholding members of Congress by examining thousands of pages of census records and historical documents," the report began.

The researchers found that 1,800 congressmen from 38 different states owned slaves, and linked slavery to present-day debates.

"The country is still grappling with the legacy of their embrace of slavery," the authors wrote. "The link between race and political power in early America echoes in complicated ways, from the racial inequities that persist to this day to the polarizing fights over voting rights and the way history is taught in schools."

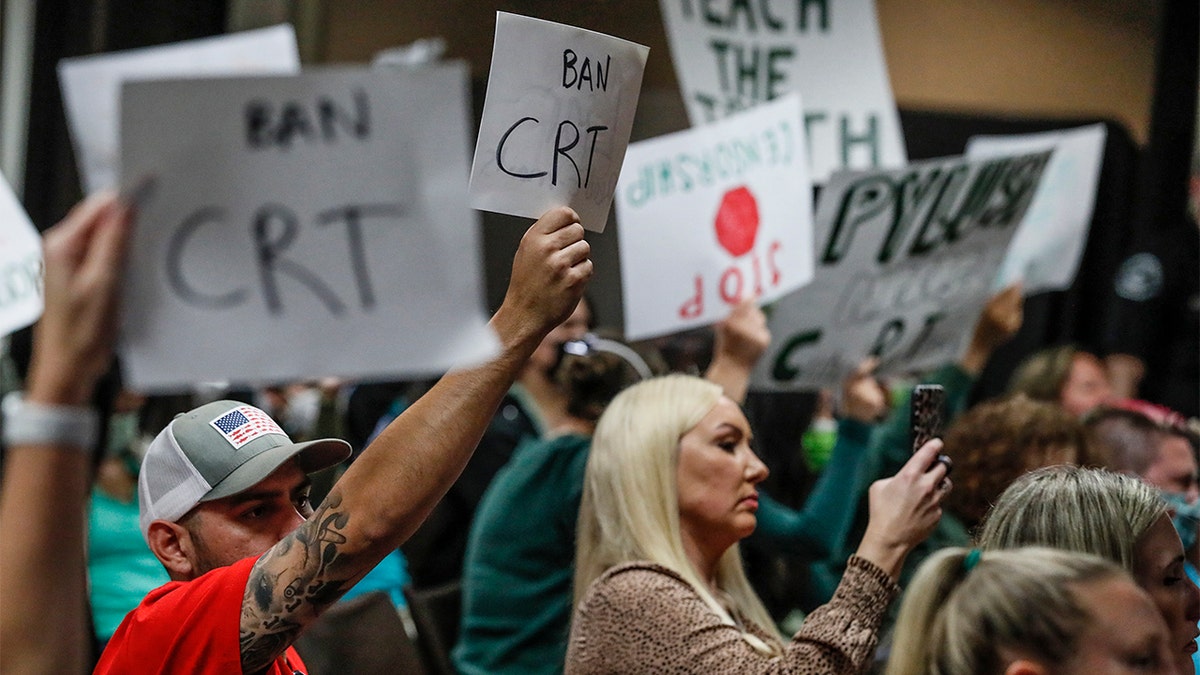

People talk before the start of a rally against "critical race theory" (CRT) being taught in schools at the Loudoun County Government center in Leesburg, Virginia on June 12, 2021. (Photo by ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS/AFP via Getty Images)

The Atlantic published a piece in December 2019 entitled, "The Fight Over the 1619 Project Is Not About the Facts," which delved into "a fundamental disagreement over the trajectory of American society."

"Underlying each of the disagreements in the letter is not just a matter of historical fact but a conflict about whether Americans, from the Founders to the present day, are committed to the ideals they claim to revere," the report read.

"The clash between the Times authors and their historian critics represents a fundamental disagreement over the trajectory of American society," it continued, before asking a series of questions about America's founding. "Was America founded as a slavocracy, and are current racial inequities the natural outgrowth of that? Or was America conceived in liberty, a nation haltingly redeeming itself through its founding principles? These are not simple questions to answer, because the nation’s pro-slavery and anti-slavery tendencies are so closely intertwined."

In November 2021, NPR published an interview with Hannah-Jones as they analyzed "the connection between slavery and modern America."

An even mix of proponents and opponents to teaching Critical Race Theory are in attendance as the Placentia Yorba Linda School Board in Orange County, California, discusses a proposed resolution to ban it from being taught in schools. (Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Education experts also made a connection between the publication of the1619 Project and the emergence of critical race theory coverage in the mainstream media. The controversial curriculum teaches that U.S. institutions are inherently racist; proponents say it's a necessary guide for students, while critics say it only serves to divide young adults by race.

"The 1619 Project likely had something to do with the emergence of CRT coverage in mainstream media," National Director of Research at the American Federation for Children Corey DeAngelis told Fox News Digital. "The project sparked a lot of debate about possible historical inaccuracies, and the Pulitzer Center website claims that about 4,500 classrooms have already included the 1619 Project's ideas in their curriculum since 2019. In fact, five school systems adopted the project broadly: Buffalo, New York; Washington, DC.; Chicago, Illinois; Wilmington, Delaware; and Winston-Salem, North Carolina."

In the months after the 1619 Project surfaced, several outlets dug into the history of CRT or shared their interpretation of the curriculum. The term had previously not been granted many headlines.

"Critical race theory is a flashpoint for conservatives, but what does it mean?" a PBS headline asked, calling it "the new lightning rod of the GOP" and analyzing its effect on the 2021 Virginia gubernatorial race.

"A Straightforward Primer on Critical Race Theory (and Why it Matters)," a Forbes report read, defining CRT as "a theoretical perspective that asserts that race is always about inequality and domination."

Many media outlets and pundits appeared to take sides in the debate.

"Republicans can't conceal history," Washington Post opinion columnist Jennifer Rubin wrote in June 2021 while pushing back against criticism of CRT.

"The panic over critical race theory is an attempt to whitewash U.S. history," Kimberlé Crenshaw, a leading scholar of CRT, wrote in the Washington Post.

CRT proponents argue the academic doctrine is not taught to elementary school children and is only shown in college-level courses, a debate which sparked several more reports on the curriculum.

"Teaching critical race theory isn't happening in classrooms, teachers survey says," an NBC News report read.

"Head of teachers union says critical race theory isn't taught in schools, vows to defend ‘honest history,’" CBS News wrote. Parents, activists and academic scholars have disputed that narrative. Dr. Carol Swain called it "ridiculous." When asked what tie, if any, the 1619 Project had to CRT, Swain noted that the theory had been around long before the project's publication.

PARENTS DISPUTE MEDIA NARRATIVE THAT CRITICAL RACE THEORY IS NOT IN SCHOOLS: ‘RIDICULOUS,’ ‘A JOKE’

DePauw University professor and media critic Jeffrey McCall agreed with Swain that CRT had been circulating well before the 1619 Project emerged on the scene, but credited the latter with having boosted the controversial curriculum's profile.

"The 1619 Project provided an extra spark to those reporting initiatives partly because of the high profile platform on which it was released, and then additionally because the Project won a Pulitzer prize," McCall told Fox News Digital. "Those two factors served to give the 1619 Project a certain legitimacy in the eyes of the broader establishment media and prompted even more attention in the news agenda. The killing of George Floyd and subsequent social unrest further intensified the nation's focus on race issues, building on race narratives that were based on the 1619 Project and CRT generally."

Academics on the other side of the debate argue the 1619 Project belongs in classrooms alongside traditional textbooks, as long as it's presented in the right way.

"I *do* think the 1619 Project *can* be an excellent tool for improving and expanding history instruction, *if* we present it as a perspective on the past (which of course it is) rather than as the ‘correct’ one," University of Pennsylvania Professor Jonathan Zimmerman told Fox News Digital.

"Give the students the 1619 Project and their state-approved textbook, and ask: what are the differences?" he continued. "Which account is ‘better’? How would we know? That exercise will teach the students much more about what history actually is--and what historians do--than giving them one interpretation or the other. The real question is whether we have enough faith in our students and teachers--and in ourselves--to do it."

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Swain was adamant that the 1619 Project has already done more damage than good, delivering a scathing review that it was the worst time for race-based reporting to have emerged.

"I think this is the worst possible time in American history for us to be dividing people along racial lines because the country is rapidly heading towards becoming majority-minority, and it may already be because, we don’t actually know who’s in this country, what the numbers are, but we do know that there are many states that already have crossed over, or they’ll be crossing over soon," Swain told Fox News Digital. "And so why would you be pushing a race agenda when…we have people that are not faring well. I mean the average American is struggling, regardless of their race. This is not the time to be dividing people. That bothers me."

"You can tell a positive story, or you can tell a story that shames White people and makes Black people angry," she added.

Critical race theory remains a hot topic in the current media climate.