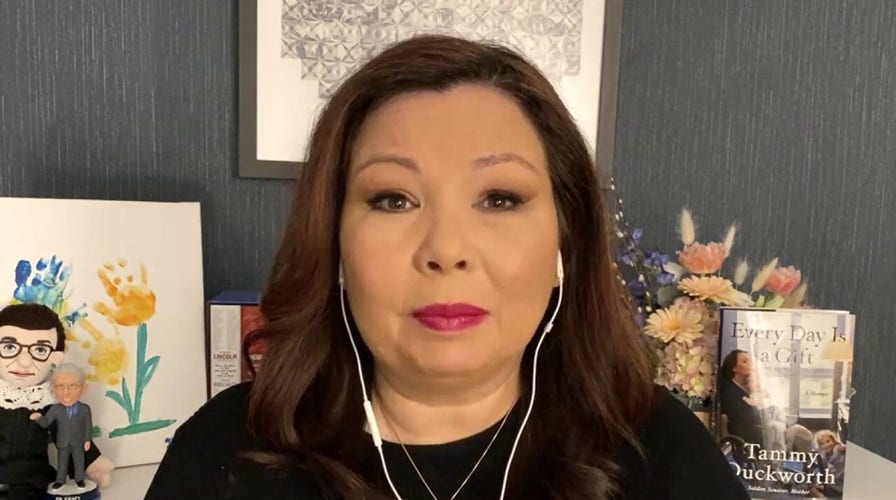

Tammy Duckworth on Afghanistan troop withdrawal: 'We need to do our jobs'

Sen. Tammy Duckworth, D-Ill., discusses Biden's hesitancy to pull troops out of Afghanistan by Trump-imposed deadline.

President Biden said at his first news conference that it will be "hard to meet the May 1 deadline" for a withdrawal from Afghanistan but troops should be gone within a year. He made a similar claim as vice president, when he said, "We are leaving in 2014. Period."

Once again it is U.S. troops who will carry the burden of the inability of U.S. leaders to end our nation’s longest war.

Veterans and military families are extraordinarily resilient. In fact, their unique ability to adapt to changing circumstances has served as a role model throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. But their willingness to serve no matter the costs has been shamefully abused.

GAYLE TZEMACH LEMMON: AMERICA'S PARTNER IN THE ISIS FIGHT, NOW DESPERATELY SEEKING CLARITY

If the United States wants to truly honor the sacrifices of this community, then elected officials must consider when, where and for how long to expose them to the perils of war. They can start by bringing home our troops from Afghanistan.

When asked one year ago about America’s duty to Afghanistan, candidate Joe Biden replied, "The responsibility I have is to protect America's national self-interest and not put our women and men in harm's way to try to solve every single problem in the world by use of force." And yet, he now appears poised to break a deal negotiated last year to bring the last of the U.S. troops home from that war.

More from Opinion

Proponents of a permanent U.S. military presence scattered across the globe argue that the term "endless war" is mere "political sloganeering," as if sending young people to fight and die abroad should fall outside the scope of public debate. Others, including the former ambassador to Afghanistan under President George W. Bush, aver that Washington should stay the course because "American casualties are down: 18 combat deaths in 2019 and four in combat in 2020."

The commodification of young American lives, whether intentional or not, is commonplace in Washington’s discourse on war, and the continuous deployment of our men and women in uniform is made possible by the political expediency of an all-volunteer force. But while Washington continues to gaze abroad, things are not OK for military families and veterans at home.

America’s military families find themselves left behind by a country in perpetual search of the next fight. Over 2,300 U.S. service members have been killed in Afghanistan and another 4,418 in Iraq. The two wars produced 1,645 major limb amputations and 328,000 traumatic brain injuries between 2001 and 2015. That is 8,363 American families irreversibly altered.

Meanwhile, garrison life offers little respite for those who do return home unscathed. There are 678 military sites in the United States with confirmed or suspected toxins in the groundwater. Black mold is also found in family housing and schools on U.S. bases.

Broken promises are an all-too-common experience for service members from a country that outwardly celebrates its military.

Veterans also face a public health crisis as suicides exceeded 6,000 each year from 2008 to 2017 at a rate of 1.5 times that for non-veteran adults. The Veterans Affairs health care system is ill-equipped to care for a generation of veterans returning home from America’s forever wars. Insufficient budgeting, mismanagement, and shockingly long wait times for care have scandalized the VA system and destroyed the trust of veterans. It is disingenuous to continue sending Americans abroad with the promise that they will be cared for upon return.

A few years ago, Aleha Landry’s Air Force spouse came home from deployment with depression and suicidal ideation – invisible wounds that many families have come to know. The mental health services available to him through the military are lacking, coupled with a stigma that discourages many from seeking services. Aleha has described her family’s experience as "excruciating...not knowing what I may or may not come home to is unsettling. It takes a toll on me as a person, on my marriage, and on my kids."

The first time Marla Bautista’s Army spouse deployed, it nearly ended their marriage. One month after losing a pregnancy and undergoing major surgery, 25-year-old Marla found herself alone at their duty station, separated from her husband and her nearest support system by thousands of miles.

The daily fear and anxiety of not knowing whether her service member was safe consumed her. Not only that, but once her spouse returned, the war came home with him in the form of post-traumatic stress disorder. "He spent many nights raging, crying, then raging again," said Marla. "It took years of counseling, medication and even rehabilitation to help our family heal."

Broken promises are an all-too-common experience for service members from a country that outwardly celebrates its military. Cash bonuses were used to lure young people into enlisting and reenlisting to keep up with the forever wars.

But nearly 10,000 members of the California National Guard who received $15,000 payments at the height of the Iraq war were ordered to repay these bonuses nearly a decade later in 2016 due to the Pentagon’s own mistake. Bonuses also don’t make up for poor access to health services, or for the emotional and financial burden placed on families when the service member comes home.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE OPINION NEWSLETTER

The lives of U.S. troops have been commoditized like shipping containers by our leaders. If we lose a couple dozen a year to combat and thousands more to service-related injury and illness, so what? Or so goes the prevailing attitude. This should concern everyone.

In the case of Afghanistan, it is time to bring U.S. troops home.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Adam Weinstein is a research fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and he served as a U.S. Marine in Afghanistan in 2012.