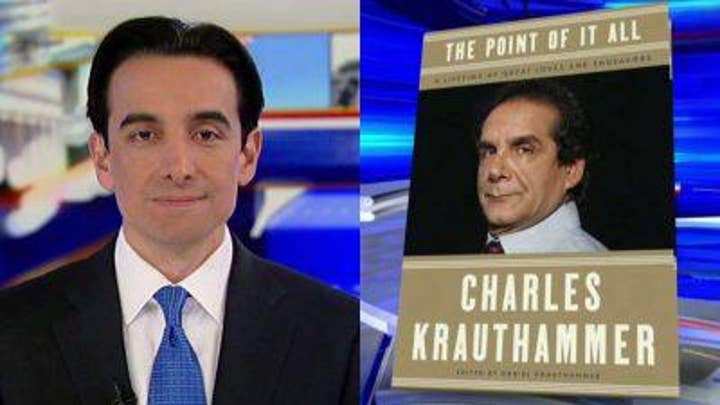

Daniel Krauthammer on his father Charles Krauthammer's writings, life and legacy

'The Point of It All: A Lifetime of Great Loves and Endeavors,' a book of Charles Krauthammer's writings collected by his son Daniel, is now available in paperback.

Following the publication last year of my father’s posthumous book, “The Point of It All,” I spoke and interviewed around the country to promote it. I met and heard from thousands of people who followed his commentary, and it was one question — above all others — that so many dearly wished they could know the answer to: “What would Charles say about this?” My father’s voice is missed, now more than ever.

In his public life, my father played a very special role. He was not just another talking head. He was a trusted guide to so many who read his columns and watched his commentary on television. As one colleague described it: “I often found myself hoping Charles would ... write about some particular issue I was struggling with so that I’d know what to think about it.” The refrain I heard over and over again from his admirers: “I feel lost without him.”

I know that feeling more intensely than anyone. But it was both moving and enlightening for me to learn that so many others feel similarly lost, adrift in a world that has become even less navigable in the time since he has gone, even less clear in its truths and falsehoods. Our politics has become more brutal, our discourse more shrill and uncharitable.

CAL THOMAS: A TRIBUTE TO CHARLES KRAUTHAMMER

Against this, my father represented something very different: an exemplar of a better kind of politics and a higher mode of discourse. That is why so many people — whether they agreed with his conclusions or not — relied on him to help them work out their own thoughts on what was happening in the world. They trusted him. He earned and retained that trust, I believe, by embodying several crucial tenets of free and open debate.

First, he was truthful. He said what he believed. He did not pull punches, alter his stance or mouth party tropes to please anyone or to mirror public opinion. There was a consistency to his positions. He wouldn’t shift them to follow changing trends. And it is remarkable to see — as perfectly illustrated in his book — how unswerving his reasoning remained on so many issues over the span of nearly four decades.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR OPINION NEWSLETTER

More from Opinion

Second, my father was logical. He would show you exactly why and how he came to his conclusions, walking you through every step of reasoning and evidence to his closing point. He was determined to make the very best argument he could for the positions he thought were right and to address the most compelling objections and counter-arguments that he found on the opposing side.

This intellectual rigor raised the quality of debate for everyone who engaged with his arguments. It helped guide others on not just what to think but how to think about important questions. Those who agreed with him better understood why they did. Those who disagreed would see a strong counterargument that forced them to defend and appreciate their own positions better. And those in between could see exactly which principles or assumptions or empirical evidence they found convincing, and which not.

Third, my father’s goal was to persuade. This may seem obvious, but it is not. Many in politics seek only to rally those who already agree with them, to discredit their opponents or to intimidate the other side. Leading others to change their mind of their own free will is no easy task.

In the end, the success and survival of democracy depend on choosing persuasion over brute force. It takes courage and restraint and perseverance. That is the kind of commitment that democracy requires of its leaders and its citizens. It requires a democratic spirit. And it requires personal virtue. The Founding Fathers recognized this. “Public virtue cannot exist in a nation without private, and public virtue is the only foundation of republics,” wrote John Adams. And as Benjamin Franklin is reputed to have said after the Constitutional Convention, the American people had “a republic, if you can keep it.” Only republican virtue could keep this democratic republic alive.

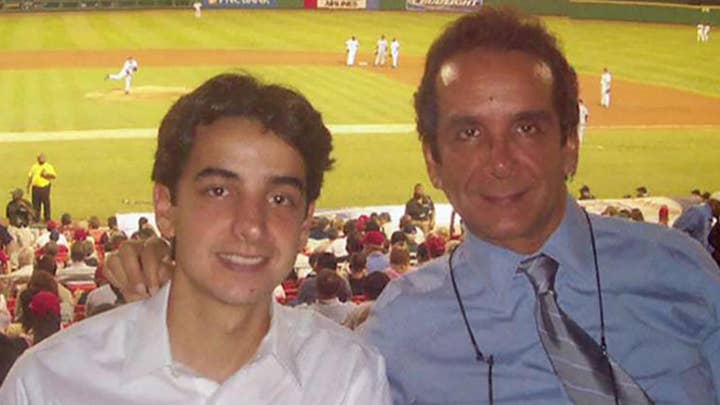

My father was a man of such virtues. And his public greatness was inextricably linked with his personal goodness — as so many who knew him and witnessed his impact on our country have observed. The most important things about my father’s life were not political, and they were not public. But he did not trumpet his personal virtues, or his personal life, in any significant way. His vocation—his calling—was in politics and the service he gave to our democracy. And he would want his memory to be based therein. But I believe we owe it to him, and to ourselves, to appreciate how fundamentally his democratic spirit derived from his humane soul. His belief in human liberty, in freedom of conscience and thought and in democratic pluralism was absolutely core to his being. But he could never have been such a strong, resonant and dearly missed voice in our politics if not for his honesty, his decency, his magnanimity, his bravery and his humanity.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

It was put best, perhaps, by his friends and colleagues, who wrote: “He was ... a giant, a man who not only defended our civilization but represented what’s best in it.”

Adapted from the preface to the paperback edition of Charles Krauthammer’s posthumous book, "The Point of It All" (Crown Forum). Daniel Krauthammer is the author of this excerpt and is the editor of the book. For more please visit CharlesKrauthammer.com.