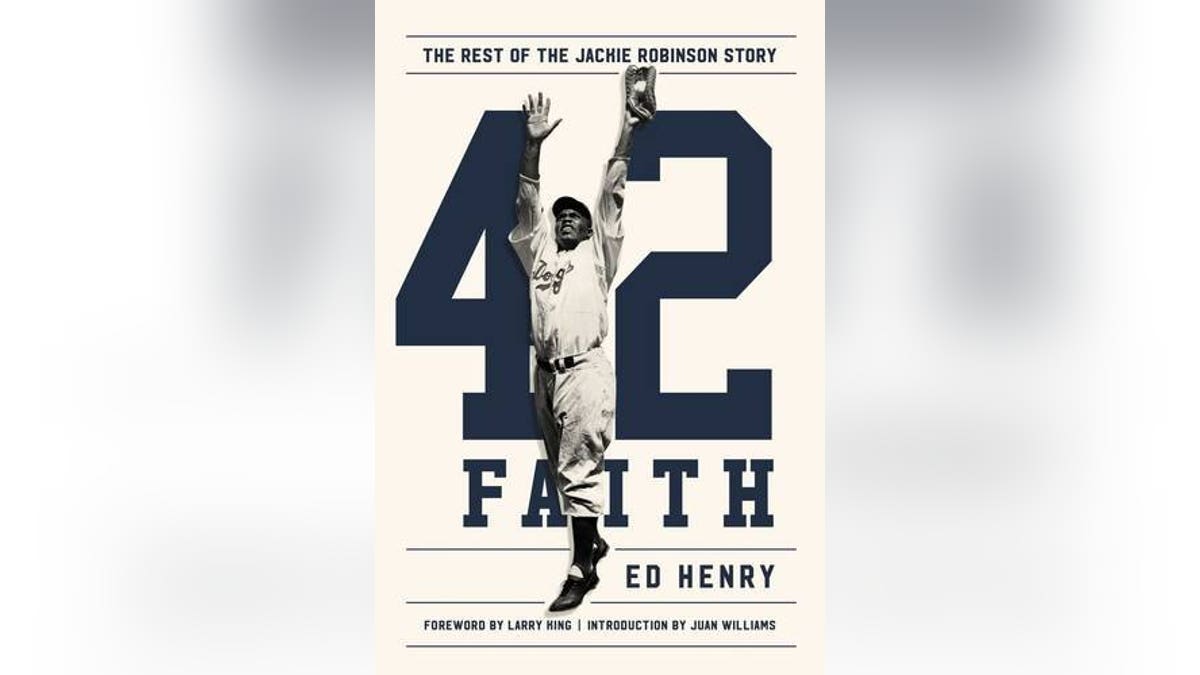

As I have traveled from coast to coast across America talking about my new book, "42 Faith: The Rest of the Jackie Robinson Story," one question keeps popping up.

The query I get over and over, whether it's from a sports talk radio host or a Fox News Channel viewer saying hello in an airport, is this: why the heck did a political reporter write a book about baseball?

The real answer is it's not just a tome about baseball. It's actually a book with previously untold details about how Robinson leaned on his faith in God to overcome steep obstacles to become the first black man to play in the big leagues 70 years ago this spring.

With the help of an unpublished manuscript I found in his personal papers at the Library of Congress, and a ream of little-noticed sermons Robinson delivered in churches across this glorious nation in the 1960's after his baseball days were over, the book shows Jackie imploring people of all races that the road to success is based on a strong faith in God and pulling yourself up by the bootstraps.

In short, we see a side of Jackie Robinson that reminds me of why I am proud to be an American.

Sure there are other reasons why I wrote a book that had nothing to do with some of the people I have been covering for the last decade, from Donald Trump to Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama. As someone who eats, drinks, and sleeps politics, it is nice to dive into a totally different subject I am passionate about.

I adore our national pastime and if you're a baseball fan, you will love the stories I got about the old Brooklyn Dodgers from Jackie's surviving teammates like Carl Erskine. I loved the note I received from a reader in Pennsylvania who said 42 Faith reminded him of attending his first game at the long gone Ebbets Field in the 1950's.

"My Dad treated me to my first vanilla ice cream and orange sherbet in a waxed paper cup with a wooden spoon," the reader wrote, "my life changed that day."

That is pure America right there. But what really drove me to write this book was listening to the hopeful message that Robinson delivered in his final days, even after all the struggles he faced on the road to integrating baseball, from people shouting racial epithets from the stadium seats to others literally threatening to gun him down.

In one sermon Robinson delivered at a church in 1967, about a decade after he hung up his baseball glove, Jackie spoke emotionally from the pulpit.

"The good Lord has showered blessings upon me," said Jackie, a man who had become a civil rights icon but was still humble and grateful. "This country and its people, black and white, have been good to me."

Robinson was speaking at a church in New Rochelle, to the north of New York City, just a few months after the "Long Hot Summer," when race riots ravaged America from Newark to Detroit.

Jackie was direct in telling the congregation that faith in God could help ease racial tensions. "If the church of the living God cannot save America in this hour of crisis, what can save us?"

In this sermon 50 years ago, Robinson also expressed skepticism about federal government assistance programs.

"My dear friends in this congregation, I think the black man is just a little [weary] of this constant talk of ‘helping’ him," Robinson said. "I think, to a large degree, the poverty programs have fallen flat on their face, coming to resemble just some more handouts, a cut higher than welfare. God helps mankind, but he helps those who help themselves."

Robinson illustrated his point by telling the congregation about a farmer who spent several long days, and a few nights, planting new crops. After a neighbor came by to inspect the results and remark that God was good, the farmer had a rejoinder.

"But you should have seen the mess this land was in before I got out here with these tools and gave God a little help," Robinson quoted the farmer as declaring.

I am taking Robinson's unifying message to Kansas City for talks this Saturday May 6 at the Negro Leagues Museum, and Sunday May 7 at the Wayne Densch Performing Arts Center in Sanford, Florida.

"I am not out to be anybody’s martyr or hero," Robinson said that day in the church. "But I think that we all ought to join hands and hearts and effort and whatever else is necessary to enlighten the world about us."

And what is more American than that?