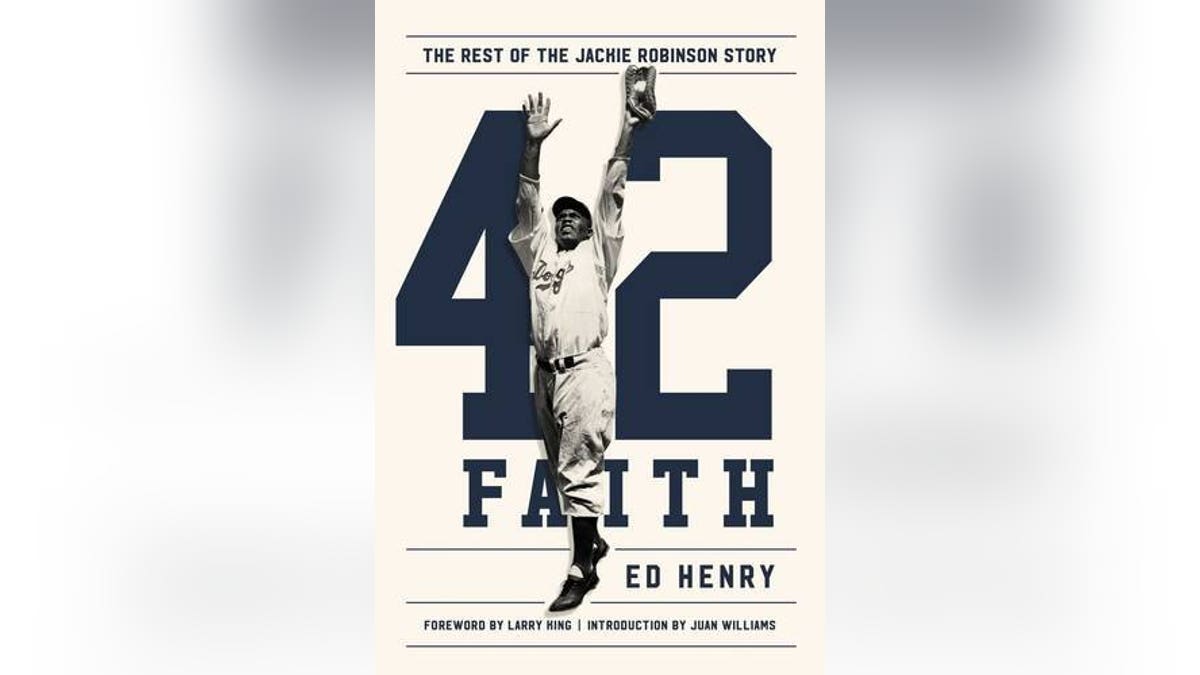

Editor's note: The following excerpt is taken from Chapter 5 of "42 Faith: The Rest of the Jackie Robinson Story" by Fox News' Ed Henry.

The path was not easier for Jackie Robinson simply because he embraced God. He was far from perfect and had a criminal record from his days in the gang, though it is clear that at least some of the arrests were racially motivated.

Jackie and some of his friends were dragged off to jail at gunpoint by a local sheriff because they had gone swimming in the reservoir.

Sure, the kids were in the wrong, but it’s hard to believe that a similar swim by white kids would have resulted in them being escorted to jail at all, let alone with weapons pressed to them. After all, Jackie had jumped into the reservoir to protest the ban on African-Americans at the local pool.

As he swam, policemen shouted, “Look there, a n*gger swimming in my drinking water. All of that nastiness, plus Robinson’s struggles with the law, have been chronicled before. But precious little time has been spent delving into how he got through all of it and still was able to rise to great heights.

Even if his gang activity was relatively minor, it was another fork in the road where he could have veered off course and never made history without some kind of intervention.

Jackie’s own daughter, Sharon, would note many years later, “You see these points in his teenage years when he could have gone in either direction.”

Mallie Robinson was Jackie’s core. She believed there was destiny from God for her son, and she continued that laserlike focus in Pasadena.

“She brought us up believing in God, knowing there was a God and also a true hell,” recalled Jessie Maxwell Wills, Mallie’s niece.

Mallie also taught her kids to get down on their knees and pray each night before bed, a habit Jackie would continue right through his days as a famous baseball player.

“Prayer is belief,” she told her kids, who attended church every Sunday at Scott United Methodist Church.

At that church, they met another critical person in Jackie’s early life: Rev. Karl Downs, a young African-American minister. Downs was only twenty-five-years-old when he took the helm of the church in 1938, so he could relate to young people.

This was like manna from heaven for Robinson, who around this time had a mounting police record.

One day Robinson and his buddies were hanging out on a street corner, when suddenly Downs pulled up in a car. “Is Jack Robinson here?” he asked. Nobody answered, including Robinson, perhaps fearing he was in further trouble.

Downs cut a distinct impression. He was a wiry guy, tall and thin, usually dressed in a tailored suit with a white shirt and necktie.

“Tell him I want to see him at junior church,” Downs said before departing. Did Mallie send him? Nobody knew for sure.

The key is that Downs got Robinson’s attention, and he was soon bonding with the man who became more than just a minister.

“He really was a sort of psychiatrist,” said a childhood friend of Jackie. “I’m not sure what would have happened to Jack if he had never met Reverend Downs.”

Downs led nothing short of a spiritual awakening for Robinson. Suddenly, all the lessons Mallie had instilled in the boy were morphing into concrete steps to help him get out of the gang in the short term and figure out how to persevere over Jim Crow long term.