Fox News Flash top headlines for April 18

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

In the fall of 1864, both Union and Confederate forces in the Shenandoah Valley found themselves trapped in a cycle of violence and retribution deaths. The Civil War is filled with nuance, tragedy and unexpected sacrifice and triumphs of the human spirit. Two such events helped end this no-win bloody cycle.

In the middle of October 1864, a Union soldier fitted a leather strap around the neck of former Baptist divinity student Private Albert Gallatin Willis. The 20-year-old Confederate, a member of Mosby’s Rangers, courageously prayed as he faced his executioners during his final seconds left on earth.

As a member of Company C of the 43rd Battalion or Mosby’s Rangers, Willis survived multiple skirmishes and harrowing narrow escapes. He was granted a furlough and traveling south toward his home in Culpeper, Virginia, with another Ranger when his horse went lame outside a patchwork of houses in present-day Ben Venue.

LAST SURVIVING MEDAL OF HONOR RECIPIENT FROM THE KOREAN WAR WILL LIE IN HONOR AT THE US CAPITOL

A local blacksmith’s hammer and anvil masked the clatter of approaching Union cavalry as they bore down on the two unsuspecting Confederates. Overwhelmed by numbers, the rebels surrendered without a fight and were taken to Colonel William Henry Powell’s headquarters. Powell ordered that one of the two men be executed in retaliation for a Union soldier who was executed days earlier.

Sergeant William T. Biedler, 16 years old, of Company C, Mosby's Virginia Cavalry Regiment with flintlock musket.

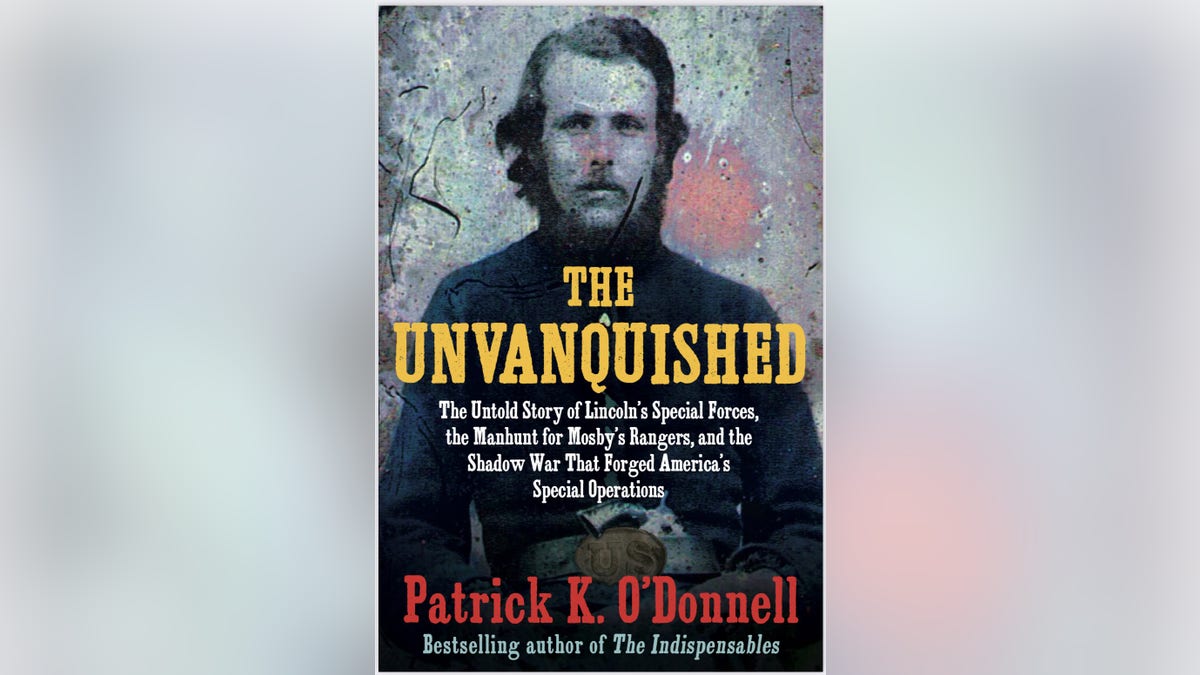

The largely unknown story of Willis, along with the stories of the Confederate Secret Service and the Union Scouts that inspired the creation of America’s special forces, is explored in my forthcoming book, "The Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln’s Special Forces, the Manhunt for Mosby’s Rangers, and the Shadow War That Forged America’s Special Operations."

After Powell discovered Willis’ religious background, he told the young Ranger he could claim an exemption as a chaplain, but the private refused. Powell then ordered the two prisoners to draw straws to determine which would be hanged.

Willis’ companion drew the shorter straw and burst into tears. "I have a wife and children, I am not a Christian and am afraid to die," the unlucky man pleaded. Willis replied, "I have no family, I am a Christian, and not afraid to die."

Unfortunately, Willis would not be the last man executed. A deadly series of slayings and retribution followed in his wake.

Bestselling author Patrick K. O'Donnell’s forthcoming book on the Civil War is titled: "The Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln’s Special Forces, the Manhunt for Mosby’s Rangers, and the Shadow War That Forged America’s Special Operations."

Col. John S. Mosby informed Confederate General Robert E. Lee of the Union executions and wrote, "It is my purpose to hang an equal number of [General George Armstrong] Custer’s men whenever I capture them." Lee concurred with Mosby’s approach to halt the violence.

So, on November 4, outside a train depot where 27 Union prisoners were held captive, Mosby planned to carry out Lee’s orders. Each man pulled a scrap of white paper from a hat. Twenty blanks. Seven marked. The unlucky seven would be executed.

Several of the men prayed aloud. Each gingerly plucked a slip of paper. Some exhaled sighs of relief. Others exclaimed, "Oh God, spare me!" A hysterical drummer boy extracted a blank slip to his great relief. The second drummer boy was not so lucky.

Mosby, hearing that the young boy was among the condemned, ordered his immediate release. The remaining 19 men who thought they had cheated death (the other drummer boy was excluded as well) drew lots again until one selected the mark.

The old train depot where the Union prisoners were held by Col. John S. Mosby’s Confederate troops. Graffiti by the prisoners can still be seen on the structure’s walls. (Patrick K. O'Donnell)

Soberly, the Confederates bound the condemned men and mounted them on horses and rode toward the Shenandoah Valley where Mosby had ordered four men to be shot and three hanged.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE FOX NEWS OPINION

Not all went according to plan, however. When one of the prisoners was granted time to pray, he managed to free his hands while kneeling down. He jumped to his feet, punched the nearest Ranger in the face, and escaped into the woods.

The surprised Confederates fired at the remaining prisoners. A misfire allowed a second man to escape. The Confederates hanged the remaining three prisoners, adorning one with a note that read, "These men have been hung in retaliation for an equal number of Colonel Mosby’s men hung by the order of General Custer, at Front Royal. Measure for measure."

So, on November 4, outside a train depot where 27 Union prisoners were held captive, Mosby planned to carry out Lee’s orders. Each man pulled a scrap of white paper from a hat. Twenty blanks. Seven marked. The unlucky seven would be executed.

When Mosby’s men returned and explained what happened, instead of executing more men, the Gray Ghost, as Mosby was known, sent a Ranger to Winchester under a white flag with a letter for Union Gen. Philip Sheridan.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

In the letter, Mosby detailed the situation, including that he captured over 700 prisoners and sent them to Richmond. He further promised, "Hereafter any prisoners falling into my hands will be treated with the kindness due to their condition, unless some new act of barbarity shall compel me reluctantly to adopt a course of policy repulsive to humanity."

One of his Rangers returned with a letter from Sheridan. Neither man ever discussed the contents of the letter, but the reprisal killings halted.