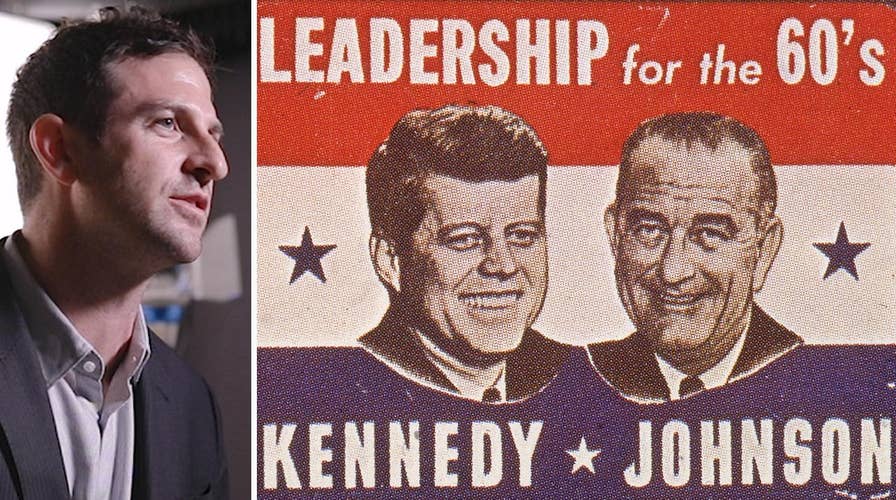

Jared Cohen: How JFK's assassination and LBJ's succession changed the course of history

Jared Cohen, the author of 'Accidental Presidents: Eight Men Who Changed America,' explains the impact of John F. Kennedy's assassination and the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson changed the course of American history.

John F. Kennedy’s path to reelection was not going to be easy. He may have charmed many Americans with his oratory skills, good looks, and youth, but that would not be enough. With heightened tensions at home and abroad, he had a weak track record on both fronts.

Soaring rhetoric was one thing, but when it came to policy, he had floundered. From the Bay of Pigs fiasco to his window dressing on civil rights, his presidency lacked any significant accomplishment.

As he geared up for reelection, he knew that winning would require a fight. He had only narrowly won the presidency in 1960. Now the country was more divided on civil rights, tensions with the Soviet Union had brought the world to the brink of nuclear war, and the Democratic Party was plagued by competing factions.

He’d have to work for a win, which meant campaigning in the South. The strategy was for Lyndon Johnson to wrangle some support since Kennedy had only narrowly won Texas in 1960.

On the swing through Texas, the president would be joined by the vice president and John B. Connally, the governor. John and Jackie Kennedy arrived on November 21, 1963, stopping in San Antonio and then Houston before heading on to Dallas the following day. He didn’t make it through the day and was shot to death at 12:30 pm CST.

Kennedy’s supporters were horrified by the idea of Lyndon Johnson as president. The two men could not have looked more different: Kennedy was young and handsome with an elevating voice, while Johnson was older and haggard with a rougher-sounding tone; Kennedy was graceful and elegant, Johnson was uncouth and used foul language; Kennedy was Harvard educated, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and decorated war hero, Johnson was an intellectual outsider with a questionable military award for his service during World War II.

The superficial differences may have favored Kennedy in the popularity contest, but Johnson had the superior skill and more impressive political background: Johnson had served in Congress since 1937 and held the Senate’s highest leadership positions, Kennedy never served in the leadership; Johnson had a legislative track record and a mastery of rules and tactics, Kennedy rarely showed up to vote and had no significant legislative achievement; Johnson had real relationships in Congress and an ability to unite the Democratic Party and work across the aisle, Kennedy was aloof and polarizing even within his own party.

When Johnson gave up the most powerful position in the Senate to serve as vice president, he knew that this was political castration. Had it been entirely up to John Kennedy, Johnson may have fared better within the administration. But others were incensed by Johnson having scrutinized Kennedy’s Catholicism and exploited his life-threatening illnesses—describing him as a “little scrawny fellow with rickets”—during the Democratic primaries.

When President Kennedy dispatched Johnson to Vietnam in May 1961, Robert Kennedy sent their brother-in-law, Steve Smith, as a minder. From the president’s perspective, there was a substantive purpose for this trip. Kennedy had sent a letter to the South Vietnamese president the previous month that had gone unanswered. He hoped Johnson could force a response to collaborate “in a series of joint, mutually supporting actions in the military, political, economic and other fields in the struggle against Communist aggression.”

When Johnson met with President Ngo Dinh Diem, he explained that the “letter represents President’s thoughts on what might be done about the situation in Viet-Nam and offers the basis for what US role might be in cooperation with GVN [Government of Vietnam].”

Diem responded point by point and agreed to respond with a letter and a joint communiqué. Johnson urged Diem to include “his views on additional assistance which he feels Viet-Nam will really need to stem Communist tide in this country” and he suggested he make “reference to [the] possible one hundred thousand increase in armed forces (over 20 thousand increase already agreed to) and measures of economic and social aid.”

Johnson did his job and by all accounts, he did it well. But despite his effort, his trip became an international joke. Some of this was of his own making and some could be linked to his detractors.

He knew how to mix with political crowds in the United States. To the Asians, he was a fish out of water. As the motorcade made its way through Saigon, he repeatedly forced the driver to stop, so that he could give South Vietnamese children free passes to the U.S. Senate.

More from Opinion

He seemed tone-deaf to the fact that they lacked any understanding of what the U.S. Senate was, let alone the economic means to ever travel outside of their country.

He compared Diem to Winston Churchill, asked photographers to capture him chasing a herd of cattle around one of the suburbs, and subjected foreign reporters to watching him get naked, dry off, and change his clothes after a hot shower.

In Karachi, Pakistan, he encountered a camel driver named Bashir Ahmed, whom he invited to come visit him in America. Ahmed took Johnson up on the offer.

The NBC reporter Tom Brokaw shared a conversation with Smith, in which the latter recalled that Johnson had a whole huddle of girlfriends— “babes,” Smith called them—around him in the evenings.

At the end of the trip, LBJ summoned Smith to his hotel suite, where, surrounded by a bunch of women and with a huge drink in his hand, he told Steve, “You go tell your brother-in-law that I behaved just fine over here.” These are the stories that dominated Johnson’s tenure as vice president.

Johnson’s power evaporated with each day he served as vice president and with no future as president of the United States. He was almost certainly going to be dropped from the ticket in 1964, although not because of Robert Kennedy’s animosity toward him. He was at the heart of a Senate investigation that was about to destroy him.

At the center of this scandal was Bobby Baker from Pickens, South Carolina, who had risen from a Democratic page to become secretary and trusted adviser to Johnson when he was Senate majority leader. There was nothing wrong with having such a trusted confidant, except for the fact that a lot of what Baker did was illegal and implicated his former boss, the vice president.

Had Kennedy not been shot and the corruption investigation gone forward, Johnson would have almost certainly been gone because they had enough evidence to bring him down, he had no advocates within the administration, and it would have been hard for him to stay on the ticket.

At the time, CBS was tracking the Bobby Baker case very closely and they may have even had the dossier, but after Kennedy’s assassination they either moved on or made a deliberate decision to drop the story.

Even without knowing the details of what they had or didn’t have, there should be little doubt that LBJ’s unexpected ascension to the presidency essentially exonerated him from his role in the Baker misdoings. Given the stakes, this was tantamount to LBJ getting the equivalent of a pardon because of the mood of the country and his ascension to the presidency.

More important, however, is the fact that had either CBS or Time-Life published the story the following week as planned, Johnson would have almost certainly been forced to resign.

Following the Presidential Succession Act of 1947, signed into law by Harry Truman, the order of succession was vice president, followed by speaker of the house. With Johnson’s ascension to the presidency, the vice presidency remained vacant until the election of 1964 catapulted Hubert Humphrey into the role on January 20, 1965. Therefore, had the dossier been published and the investigation continued, the next in line would have been John W. McCormack, a Democrat from Boston who had assumed the speakership following the death of Sam Rayburn.

In today’s world of social media, it would be impossible to keep such information a secret. In 1963 the country had just gone through such a head-snapping transition that nobody including the media had the stomach for a presidential scandal. With Kennedy’s assassination, you had a “cool, elegant, Ivy League, attractive family from Massachusetts with their distinctive style and all the people it attracted,” recalled Brokaw, and then, “suddenly we do a 180 and we get the outsized Texan with his not much of a feel for language, including when he stepped off the plane at Andrews [Air Force Base].”

Johnson handled the transition in a strategic manner. He understood the importance of showing unity with the Kennedy team. He understood the importance of having Jackie Kennedy in the picture while he took the oath of office on the plane two hours and eight minutes after JFK’s assassination.

He approached his early days with humility and deference to his predecessor. In an effort to compensate for oratory skills that he knew to be inferior to those of his predecessor, he choreographed the gestures and tone of his early speeches, particularly during his first address to Congress.

All of this was masterly theatrics. He worked the phones, drank with old colleagues, and did what he did best, which was playing the politics.

Civil Rights

The election of John F. Kennedy felt like a euphoric moment for black America. African- Americans heard Kennedy pay lip service to civil rights and they believed he was serious. “The Kennedys had not just said segregation was illegal, they said it was immoral,” Jesse Jackson recalled.

“It was the first time I ever heard a prominent white politician say that segregation was an abomination. That was a big deal.” Many in the black community were ready to put all of their hopes and faith in Kennedy.

It didn’t take long for civil rights leaders to begin questioning how serious the Kennedys were about effecting change. They had heard JFK say the right things, but when tested, he proved unwilling to act.

Nowhere was this more obvious than on September 15, 1963, when members of the Ku Klux Klan rigged Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church with dynamite and killed four young girls, injuring many others.

The next day, President Kennedy said, “If these cruel and tragic events can only awaken that city and state—if they can only awaken this entire nation to a realization of the folly of racial injustice and hatred and violence, then it is not too late for all concerned to unite in steps toward peaceful progress before more lives are lost.”

Former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, who grew up in Birmingham and remembers that day well, describes how there were some skeptics who thought Kennedy was prepared to talk about civil rights, but it was unclear if he could actually do anything. His reaction to the bombing proved to be “great words,” but the assassination precluded this from happening.

JFK’s assassination terrified black America. In addition to the same sorrow and fear felt throughout the country, there was an even more daunting reality that they were now stuck with Lyndon Johnson.

For civil rights activist Jesse Jackson, Kennedy’s death was a critical inflection point in the civil rights movement. He remembers walking across campus at North Carolina A&T and hearing it on the radio.

“I couldn’t believe it,” he remembered. “Presidents didn’t get killed. Lincoln had been killed, but that was so long ago. I felt like there were two assassinations, Kennedy and civil rights. I would eventually realize that I was wrong.”

When Kennedy died, standing in his place was Lyndon Johnson, who was a southerner who used the “N” word with advisers and friends and who as President Barack Obama later pointed out opposed every piece of civil rights legislation during his first twenty years in Congress and “once call[ed] the push for federal legislation a farce and a sham.”

As Senate majority leader, Johnson in 1957 told President Dwight Eisenhower he would not introduce the civil rights bill in its current form, as it would fracture the Democratic Party.

A version of the bill was eventually introduced and it did pass, but Johnson made sure to slice and dice it to such an extent that he could tell his segregationist colleagues in the South—many of whom he would need when he made his 1960 run for the presidency—that the bill had no teeth and they need not worry.

At the same time, he felt the bill gave him the credential to tell civil rights leaders that he was trying and to show northerners that he was more than just a southerner.

As president, Lyndon Johnson made such an extraordinary ideological transition that even today many people are baffled by it. Getting the 1964, 1965, and 1968 Civil Rights Acts passed was something that only he could do.

There are theories about Johnson’s transition, including his biographer Robert Caro’s suggestion that growing up an underdog, Johnson came to identify with the civil rights movement.

Johnson’s transition was likely driven by political pragmatism. This was not unlike Andrew Johnson’s transition one hundred years earlier, only this time around the president was on the right side of history.

In that sense, his transition was a strategic move by a pragmatic politician who understood the changing mood of the country. As colleagues witnessed his shift, they concluded that one of two things had happened: Either he had had a personal transformation, or the pragmatism of the moment had awakened him to the reality that the country was about to explode and unless he did something to stop it, the consequences would be on his watch.

It’s also likely that President Johnson believed only he could do it. He had the relationships, the understanding of Congress, and legislative savvy.

Over the years Johnson had accumulated a prodigious amount of political capital and held a strong belief that if you do the first favor for your colleague, they are indebted to you for life.

As Senate majority leader and minority whip, Johnson had taken care of a lot of legislators and he expected them to rally behind him. With civil rights, he chose to cash in his chips.

The job was still tough—he had to rely on Everett Dirksen, Senate minority leader from Illinois, to get the bill passed, for example—but as he gamed it out, he could see a path forward.

Second, and more superficially, LBJ had the right pedigree, a white southerner from Texas who had been a segregationist.

Former President George H. W. Bush told me the reason why only Johnson could have passed civil rights in the 1960s: “You had a southern president calling his former Senate colleagues in the South, and in that wonderful Texas drawl of his, telling them to do the right thing,” he said. “JFK’s Boston twang would not have had the same effect. LBJ knew how to push.”

Third, Johnson was tough, even ruthless in deal-making. He was willing to take on the southern establishment, work the phones, threaten, cajole, extort, whatever he needed to do.

A fourth reason for his success on civil rights is that, unlike Kennedy, he needed the Civil Rights Acts to prove he could make the impossible happen and show that he “wasn’t the bumpkin from Texas that everyone—the antithesis in some ways of John F. Kennedy—thought him to be,” as Rice puts it. That meant he was going to push harder and achieve more than anybody believed could be done.

Finally, Johnson understood how to find the balance between the aspirations and needs of the civil rights community and segregationists. “[Kennedy] would go to Harlem and kiss a black baby because that’s what good liberals did,” recalled Jesse Jackson. “But Johnson launched his campaign in Appalachia, where the poor, racist white people were. He understood that you needed to bring them along.”

If these were the qualities that uniquely positioned Johnson to lead on civil rights, it was the 1964 presidential election that gave him the political opportunity to make his first big legislative bet with the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

It was a bold move that paid off, and on the evening of July 2, 1964, he signed it into law.

Recalling the founding fathers and their call for each generation to fight for, renew, and enlarge the meaning of freedom, Johnson told the nation that “now our generation of Americans has been called on to continue the unending search for justice within our own borders.”

This act of legislation, he said, will make it so “those who are equal before God” can “now also be equal in the polling booths, in the classrooms, in the factories, and in hotels, restaurants, movie theaters, and other places that provide service to the public.”

Upon accepting his party’s nomination on August 27, he said, “I ask the American people for a mandate—not to preside over a finished program—not just to keep things going, I ask the American people for a mandate to begin.”

Despite the fact that Johnson had taken on such a polarizing issue, his legislative success emboldened him as he sailed to a landslide victory in the 1964 presidential election, the greatest validation of his political career.

This enabled him to throw his weight around on Capitol Hill, something that would be required to get additional legislation passed. He cautioned Senators Al Gore of Tennessee, William Fulbright of Arkansas, and Robert Byrd of West Virginia that if you can’t vote for civil rights legislation and you can’t support it, don’t get on the floor and start speaking against it. Neither Gore nor Byrd heeded his advice.

The sequencing of the legislation was important. Johnson knew that starting with voting rights would risk the entire project, but if he could build pre-election momentum, win in 1964 in his own right, he could go for the big push.

This is what he did and it required patience from civil rights leaders. But they saw from the 1964 act that Johnson was deadly serious about this agenda. Passing the law was one thing, but implementing it was another and Johnson was ready to do this.

For many in the black community, the 1964 Civil Rights Act was the seminal moment when they realized the president was serious. They had seen his support for the 1957 bill for what it was, a token piece of legislation that paid lip service to civil rights, but had no real teeth. But the 1964 act was a big deal and risky for Johnson.

Kennedy’s shadow lingered over him and this was a gamble for a man who hadn’t yet been elected in his own right. The fact that he had to fight so hard made it meaningful.

If Johnson was prepared to go further than the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the Selma-to-Montgomery marches of 1965 pushed him over the edge.

The incidents leading up to the marches—the bombing of a church in Birmingham and the city’s Sheriff Bull Connor allowing beatings on the street—all of this had an effect on President Johnson.

When Alabama police attacked nonviolent activists marching on the Edmund Pettus Bridge on March 7, he knew things had reached a breaking point.

On March 15, Johnson addressed a joint session of Congress and pleaded with legislators to introduce and pass the voting rights bill.

It was a dramatic speech and an extraordinary plea by a president of the United States. He was staring calamity in the face. This was tantamount to the Civil War and Appomattox, he told Congress, and cautioned that time was running out.

Within two months, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, and in his second term Johnson signed into law the Fair Housing Act, which together with the 1964 legislation changed the country forever.

Whether Johnson was driven by concern for his legacy or change of heart is irrelevant. He was a creature of the Senate and was used to strong-arming southerners.

He looked at the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act and saw them both as something he could accomplish.

He knew how to get there because he knew the Senate. The tradecraft was familiar and involved morally blackmailing legislators, exploiting his detailed knowledge of congressional rules and procedures, and cutting deals.

This was his comfort zone and he was uniquely positioned to deliver. But foreign policy was a different matter altogether.

The Slippery Slope

Lyndon Johnson inherited a very difficult hand on foreign policy and his fatal flaw was not recognizing this. Had he known how poorly the cabal of Kennedy men would advise him, he may have reconsidered keeping them.

The vice presidency was a low point for him, a protracted reminder that his rambunctious personality and southern ways didn’t fit with the Kennedy crowd.

When he did opine on foreign policy as vice president, he appeared churlish, such as during a private briefing that CIA director John A. McCone had provided him on the Cuban Missile Crisis at the president’s request.

During the briefing, which McCone recorded in a memorandum of conversation, Johnson foolishly suggested that the U.S. conduct “an unannounced [air] strike [on Cuba] rather than the agreed plan [of a naval blockade].”

When he became president, the personality differences with Kennedy’s advisors would not have been an issue if the men he inherited wanted the same thing, or if there had been no animosity between them. But Johnson was surrounded by people who were hostile and still wrapped up in his predecessor. They didn’t want him to succeed and some were deeply resentful.

The love affair between New England intellectuals and Kennedy baffled Johnson, who saw himself as a master of the Senate.

“It was the goddamndest thing,” he later told historian Doris Kearns Goodwin. “Here was a young whippersnapper, malaria-ridden and yallah, sickly, sickly. He never said a word of importance in the Senate and never did a thing . . . somehow, with his books and his Pulitzer Prizes, he managed to create the image of himself as a shining intellectual, a youthful leader who could change the face of the country.”

Beyond Special Assistant to the President Arthur Schlesinger and Attorney General Robert Kennedy, the Kennedy men who stayed on and actually showed up for work were intimidating.

This was particularly the case in areas where his time in the Senate had proven unhelpful, mostly foreign policy. He had a basic insecurity when he came up against men like Robert McNamara and McGeorge and William Bundy.

At times this led him to brash actions like repeatedly threatening to fire them and creating a culture of fear, whereby various secretaries and generals were reluctant to share bad news. This kind of schizophrenic behavior deepened tensions within his own staff.

When taken out of a familiar social environment, Johnson struggled to assert himself in meaningful ways on foreign policy, particularly when it came to high-brow elites talking about world affairs.

He was blinded by a mixture of admiration and intimidation from these men he called “the Harvards,” who mocked him behind his back.

He felt superior to them in political craft, but also felt he needed their ideas and content. He didn’t necessarily like them, and throughout his presidency, he found them overbearing, dogmatic, and patronizing in different ways. But he felt that while he understood the politics, foreign policy was their world.

He was impressed by Secretary of State Dean Rusk, a fellow southerner, who had gone to Oxford on a Rhodes scholarship and run the prestigious Rockefeller Foundation.

Johnson was equally impressed by National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy, whose family had basically founded Harvard and who at 34-years old had become the youngest dean of faculty in the university’s history.

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara was the biggest brainiac of the group. He had gone to Harvard Business School and taught there as a professor, later becoming president of the Ford Motor Company. Upon meeting him, LBJ was so wowed by his brilliance that he recalled almost being able to hear the “computers clicking away” in his brain.

The biographer Robert Dallek likens Johnson’s initial “admiration for and trust in McNamara as almost worshipful,” and Kearns Goodwin recounts a 1974 interview with White House press secretary George Reedy in which he claimed LBJ copied McNamara’s restaurant orders for weeks in some kind of venerative attempt to emulate the upper class.

None of these men respected President Johnson and he knew it. The truth is, they saw him as an unrefined, vulgar man who pissed in sinks, displayed his manhood, and took meetings from the toilet.

He was stuck with the Harvards because he refused to extricate himself. “Without them, I would have lost my link to John Kennedy,” Doris Kearns Goodwin recorded Johnson as saying, and “without that, I would have had absolutely no chance of gaining the support of the media or the Easterners or the intellectuals. And without that support, I would have had absolutely no chance of governing the country.”

He should have gotten rid of the Kennedy crowd, who perhaps in pursuit of their own agendas—or out of fear for how he would react to the truth—gave him misguided information about Vietnam.

Lyndon Johnson lacked the courage he exhibited on civil rights, which is part of why he kept them.

He was determined to be a great domestic president and foreign policy crises were an unfortunate reality that he had to address.

At first this meant resisting further escalation and holding out for a peaceful settlement. But soon, fearing he would be the one to lose Vietnam, he escalated and then escalated further.

The first U.S. Marines landed in Da Nang on March 8, 1965, a significant escalation from the advisors who had previously been deployed. By the end of the year there were 189,000 troops in Vietnam and two years later that number exceeded 500,000.

Johnson continued the escalation in Vietnam though he knew it was a mistake. He was trapped by Kennedy’s legacy. Trapped by politics. Trapped by his advisers. Trapped by his own demons.

Both Eisenhower and Kennedy had pledged to defend Vietnam from communism and each had taken the escalatory steps necessary to do so.

If Johnson didn’t do the same, how would he explain that he lost it?

“Everything I knew about history,” he later reflected in an interview with Kearns Goodwin, “told me that if I got out of Vietnam and let Ho Chi Minh run through the streets of Saigon, I’d be doing exactly what they did before World War II. I’d be giving a big fat reward to aggression.”

In retrospect, this fear seems misguided. But for Johnson’s generation, this was a credible fear. Memories of Munich endured. He had lived through the failure of appeasement. He remembered how many had criticized Roosevelt for his delay in entering the war.

Why did it take Pearl Harbor to drive the U.S. into the war? Johnson saw Vietnam as bigger than Ho Chi Minh. It was about the threat of communism, Soviet progress, and the big red arrow taking over the map. It was the Domino Theory.

The prospect of losing Vietnam terrified him. He was overwhelmed by the contradiction, a war we couldn’t win and a war we couldn’t afford to lose.

“If I don’t go in now and they show later I should have gone then they will be all over me in Congress,” he remarked. “They won’t be talking about my civil rights bill, or education, or beautification. No sir. They’ll be pushing Vietnam up my ass every time. Vietnam, Vietnam, Vietnam.”

By May 1964, he was well aware of how far he had gone down the rabbit hole. During a May 27 call with McGeorge Bundy to discuss a proposed mission to North Vietnam to be headed by the Canadian diplomat Blair Seaborn, Johnson lamented,

“I just stayed awake last night thinking of this thing, the more I think of it, I don’t know

what in the hell . . . it looks to me like we’re gettin’ into another Korea. It worries the hell out of me. . . . I don’t think we can fight them 10,000 miles away from home and ever get anywhere in that area. I don’t think it’s worth fightin’ for and I don’t think we can get out. And it’s just the biggest damned mess I ever saw. . . . What the hell is Vietnam worth to me? . . . What is it worth to this country?”

He refused to pull the cord on Vietnam and as a result, Johnson’s blunder has cast a dark shadow over his presidency, but Kennedy was as capable of plunging the U.S. into war in Southeast Asia.

Both were foreign policy novices. Both were cold warriors who believed in the Domino Theory that if one country falls to communism, others will fall as well.

The guardians of Kennedy’s reputation, most notably Schlesinger, created a myth of withdrawal around 1963. They argue that he would not have put 500,000 troops into Vietnam. He is right that it was not in Kennedy’s nature to, especially when he understood the political ramifications of losing Vietnam in an election year.

McNamara famously recalled an October 2, 1963, meeting in which President Kennedy approved a recommendation to withdraw 1,000 men by December 31, although some historians have speculated that the reductions in 1963 were part of a troop rotation home and were meant to put pressure on South Vietnam to reform.

Despite these assertions and recollections, Kennedy had accelerated the deployment of Americans into Vietnam. Before his death, he had already increased the number of American military advisers from around seven hundred to more than sixteen thousand, which far exceeded the cap on advisers established by the 1954 Geneva Accord. He also grew the foreign aid package from $223 million to $471 million.

Another factor to consider is the South Vietnamese coup and subsequent assassination of its president, Ngo Dinh Diem, which the Kennedy administration backed just three weeks before JFK was killed.

If Kennedy favored disengagement, why did he not do more to stop the Diem coup? In fact, by not making any decision on the fate of President Diem, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. who at the time served as ambassador to South Vietnam and was a harsh critic of Diem, found himself with a free hand to encourage the coup.

Kennedy didn’t live long enough to experience the disastrous effects of Diem’s assassination. But as former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger says, the circumstances could have pushed Kennedy to a point of no return.

“It is even conceivable,” he speculated, the “odd mixture [of] people who put [the troops into Vietnam] like McNamara and Bundy didn’t actually want to win. They would have liked to win the war, but they thought there was a measured way that you could get to negotiations.”

Had Kennedy survived, he may have tried to find some kind of negotiated settlement, but much as Truman found with Mao, he would not have found a willing party in Ho Chi Minh.

Vietnam was a very different context from the Cuban Missile Crisis, and what Kennedy failed to appreciate is that Ho Chi Minh and the Vietcong wanted total victory.

It is impossible to know at what point down the path of escalation he would have realized this, or whether he would have escalated to push Ho Chi Minh to the bargaining table. But this, too, would have failed and we can certainly speculate that Kennedy would have been left with no choice but to escalate further.

Johnson is held responsible for the scale of Vietnam, but the escalation of troops was dictated by the “slippery slope” problem where we find ourselves in a situation without an endpoint.

It was Kennedy who started down that path. If we look at the Diem coup, Kennedy would have faced the same dilemma as Johnson.

The assassination of Diem committed the U.S. to Vietnam and that was his doing. “What were you supposed to do? Assassinate Diem, then put in a government that was never going to work, and then leave?” Rice asks. “I just think this was the inexorable pull of trying to find a place where Vietnam was stable and I think they both would have done it.”

Another factor that makes it difficult to contrast Kennedy and Johnson is the 1964 presidential election. The election politicized Vietnam in a way that made escalation easier to sell to the American people.

Senator Barry Goldwater, who was the Republican nominee for president, accused the Democrats of being weak on communism in what was effectively a dare for Johnson to double down on Vietnam.

This was not an outlandish position. Big strategic thinkers, Cold War experts, and policymakers of all stripes believed they were attempting to contain an inexorable communist movement led by the Soviet Union.

As with civil rights, Johnson’s landslide victory in 1964 gave him a mandate on Vietnam. But while he used that mandate to make the right decisions on civil rights, he floundered on Vietnam.

By the end of the war, 58,220 American soldiers had lost their lives and more than 250,000 South Vietnamese had been killed.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE OPINION NEWSLETTER

Herein lies one of the greatest foreign policy challenges faced by all presidents. Rice explains that “when you are in that situation, there are all the sunk costs and all the credibility issues policy-makers have to navigate.”

The legacy of Vietnam came up when the administration was in trouble in 2006 and 2007 in Iraq. So as the memories of Munich were fresh for Johnson, the images of Vietnam lived on in the White House more than half a century later and still do.

The tragedy for Johnson is that Vietnam overshadows his domestic achievements. The loss for the country is that had Vietnam not gone south, LBJ may have had another four years in office to continue advancing civil rights.

Had this happened, he would have died just two days after leaving office in 1969. Most presidents go into office hoping to do great things. Sometimes circumstances or missteps make them do things that are not great, that are foolish or disastrous.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

We cannot diminish what Johnson did on the domestic side. He was a president who thought big about trying to change America. And some of it worked and some of it didn’t.

The part that worked left an indelible mark on the country that would be felt for decades to come.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM JARED COHEN

This essay is adapted from "Accidental Presidents."