D-Day veteran recalls invasion of Normandy: Let's get the hell out of this plane

101st Airborne veteran Eugene Deibler is uncomfortable being called a hero; Greg Palkot reports.

Walter Ehlers remembered waving goodbye to his brother Roland as they prepared to board different transports in Southampton, England on June 4, 1944. The Kansas farm boys had fought side by side in North Africa and Sicily. Now, in different units, they promised to meet on the beach in France.

Two days later, on June 6 – exactly 75 years ago – Walter was part of the vast armada crossing the English Channel on D-Day.

“There were ships in front of us and to each side of us for as far as we could see,” Walter recalled in his speech at Normandy on the 50th anniversary of the invasion. “By the time we were part way across, the ships behind us seemed not to end. We looked skyward where planes from horizon to horizon headed toward Europe.”

NEWT GINGRICH: REMEMBERING THE HEROES OF D-DAY

“When we got near the beaches, battleships and cruisers were firing toward shore,” Walter added. “We could hear bombs exploding in the distance. There was such firepower from the ships and planes that we didn’t expect much resistance on the beach.

They were wrong. Among 160,000 Allied troops, there were 10,000 casualties that first day, including 4,000 killed in action.

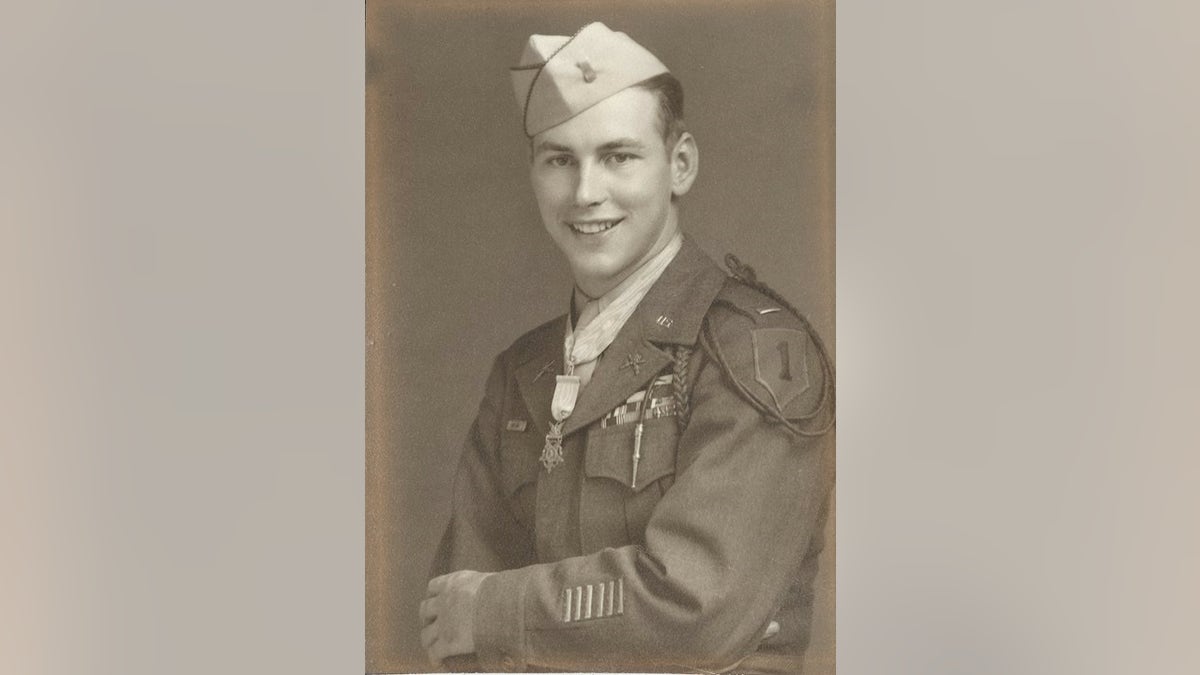

Thirteen soldiers, including Walter Ehlers, were awarded the Medal of Honor for acts of valor on D-Day and in the weeks that followed. Only four of them survived the war. They would be the first to say they were not alone in going above and beyond the call of duty. But their stories reflect the courage, endurance and sacrifice that typified the Greatest Generation.

"Hero" is a word the Greatest Generation applied to others, never themselves. As Walter often said, he was just doing his job.

Pvt. Carlton W. Barrett, just 5-foot-4, was neck-deep in the water as he struggled toward shore. Yet he plunged back into the surf, again and again, to keep fellow soldiers from drowning. His Medal of Honor citation states:

Refusing to remain pinned down by the intense barrage of small-arms and mortar fire poured at the landing points, Private Barrett, working with fierce determination, saved many lives by carrying casualties to an evacuation boat lying offshore. In addition to his assigned mission as guide, he carried dispatches the length of the fire-swept beach; he assisted the wounded; he calmed the shocked; he arose as a leader in the stress of the occasion.

Barrett retired from the Army in 1963.

Technician Fifth Grade John J. Pinder Jr. was wounded just yards away from his landing craft. Yet he waded the 100 yards to the beach, delivering his radio. Then he was back in the water, salvaging more communication equipment. His citation states:

On the third trip he was again hit, suffering machinegun bullet wounds in the legs. Still this valiant soldier would not stop for rest or medical attention. Remaining exposed to heavy enemy fire, growing steadily weaker, he aided in establishing the vital radio communication on the beach. While so engaged this dauntless soldier was hit for the third time and killed.

Pinder was one day shy of his 32nd birthday.

The only general on the beach in that first wave was the son of one president and distant cousin to the commander in chief, 56-year-old Theodore Roosevelt Jr.

Roosevelt’s Medal of Honor citation stated:

Although the enemy had the beach under constant direct fire, Brigadier General Roosevelt moved from one locality to another, rallying men around him, directed and personally led them against the enemy. His valor, courage, and presence in the very front of the attack … inspired the troops to heights of enthusiasm and self-sacrifice.

Five weeks later, still leading troops in France, Roosevelt died of a heart attack.

On June 9, eight miles inland, Staff Sgt. Walter Ehlers’ platoon came under heavy fire. He attacked a German patrol, killing four of them. He led a bayonet charge, and took out two machinegun nests and a mortar position.

The next day, Ehlers and another soldier drew enemy fire toward themselves so others could withdraw. Both were wounded, yet Ehlers dragged his injured comrade to safety. His citation noted his “intrepid leadership, indomitable courage, and fearless aggressiveness” that served “as an inspiration to others.”

Not long after, Walter Ehlers learned that his brother had died on Omaha Beach.

“I still can’t talk about him without bringing tears to my eyes,” Walter said in an interview 60 years later. “He was my hero until the day he died. He still is.”

"Hero" is a word the Greatest Generation applied to others, never themselves. As Walter often said, he was just doing his job.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

On this 75th anniversary of D-Day, be grateful for those who did their jobs and pray for the strength to follow their example if called upon.

“Without freedom there is no life,” Walter told the audience at Normandy in 1994. “And … the things most worth living for may sometimes demand dying for.”