Reagan's Legacy: 'Tear Down This Wall'

A look back at perhaps Reagan's most famous speech, and his demand to Gorbachev at the Berlin Wall

There are few phrases that stand alone in American history that encapsulates American exceptionalism: Franklin Roosevelt’s “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself;” John Paul Jones’s “I have not yet begun to fight;” and Abraham Lincoln’s “government of the people, by the people, for the people.”

Thirty years ago, the Great Communicator added another phrase for the ages.

In the 1980s, the Reagan administration took a decisively stronger tone against the Soviet Union than previous administrations, especially Richard Nixon’s pure-intended-but-failed détente.

In 1983, Reagan called the USSR “the Evil Empire,” sparing no ambiguity in where it stood in relation to the free world. He never visited Eastern Europe, save for Moscow once in 1988, a cold shoulder for the Cold War. SALT II, a nuclear arms reduction treaty that was Carter’s main goal for the Soviet Union, was immediately thrown away for another, more favorable treaty to the United States.

The Soviet Union went through four leaders within the eight years of Reagan’s presidency: the thuggish Leonid Brezhnev, the intellectual but provocative Yuri Andropov, the forgettable Konstantin Chernenko, and the reformer Mikhail Gorbachev.

The first three died in such a short period of time that Reagan had frustratingly said to Nancy, “How am I supposed to get anyplace with the Russians if they keep dying on me?”

It was finally Gorbachev who took a serious interest in reforming – not destroying, but reforming – the Soviet Union, and Reagan took that chance.

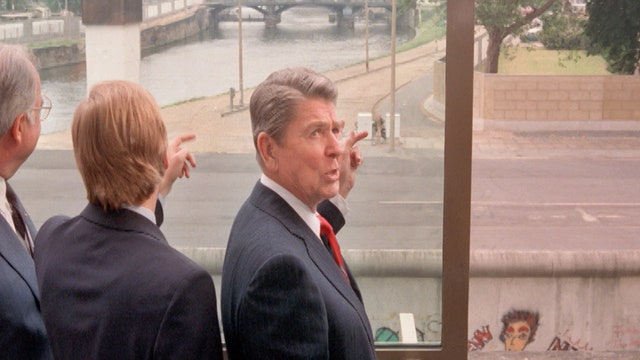

It was the year 1987; President Reagan visited West Berlin for only the second time in his presidency, in commemoration for the city’s 750th anniversary.

He spoke in front of the eighteenth-century Brandenburg Gate with West German President Richard von Weizsäcker, Chancellor Helmut Kohl, and West Berlin mayor Eberhard Diepgen behind him. Crowds waved American and German flags.

In perhaps a throwback to John Kennedy’s “Ich bin ein Berliner” over twenty years earlier, Reagan spoke some heavily accented German: “Es gibt nur ein Berlin.” There is only one Berlin.

It had been over forty years since the end of the Second World War, when the Allies divided and conquered war-torn Germany, and for many in the audience, during their entire lives Berlin been a divided city.

The first phase of the Berlin Wall – die Berliner Mauer in German – was constructed in the early 1960s, in response to an exodus of the intelligentsia from the East. Hundreds of escape attempts had occurred within those twenty years, all risking their lives for freedom.

To hear the president of the United States – the president of the free world, the only man who can and will stand up to the Soviet Union and their oppressors – say factually, objectively, and truthfully, that there was one city, that must’ve resonated with them.

“Behind me stands a wall,” Reagan said to the crowd, with the full view of the graffiti-covered monument, “that encircles the free sectors of this city, part of a vast system of barriers that divides the entire continent of Europe... Standing before the Brandenburg Gate, every man is a German, separated from his fellow men. Every man is a Berliner, forced to look upon a scar.”

The audience, flags and hands waving, looked to him. Hope. Optimism. Freedom. It was all there.

“There is one sign the Soviets can make that would be unmistakable,” Reagan continued, “that would advance dramatically the cause of freedom and peace. General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization: Come here to this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate!

“Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

It was a command heard ‘round the world, and immediately entered the history books.

Some still disagreed with its message, such as the Washington Post, which published an oped the day after making the case that Germany should always be divided. “It's just that, considered as a unified nation, in a world parched for peace, the Germans are not quite ready for self-government,” wrote Frank Getlein. He argued with irreparable bias that Germany, whenever it had been united, caused war and destruction. Take the country under Adolf Hitler, when he united the decrepit Weimer Republic and turned it into Nazi Germany; take Imperial Germany under the Kaisers, with a powerhouse of a military in World War I. Getlein argued that, for such a short history of modern Germany, it certainly had caused a lot of deaths.

Luckily, no one listened to Getlein or the Post.

It was Reagan – provocative to some, strong to others – who looked at the Soviet Union straight in the eye, and did not blink. It was Reagan who, along with other political heavyweights such as Margaret Thatcher of the United Kingdom and Pope John Paul II from Poland, who pressured and commanded Mikhail Gorbachev to reform the Soviet Union to nonexistence.

It was prophetic. On November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall began deconstruction as a mass of East and West Berliners climbed over it, took sledge hammers, and celebrated new freedom. Referring to the former and hardline Communist leader of East Germany, Erich Honecker, one East Berliner laughed: “Honecker thought it would take a hundred years for the Wall to fall. I bet he can't believe what is happening now.”

Soon, each of the other Warsaw Pact countries followed suit: Hungary, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Yugoslavia, and others. They all looked to the fall of the Wall as an example of the power of the people against an oppressive government. And the people looked to Reagan as the fire to light that spark for freedom.

Craig Shirley is a presidential historian and bestselling author of four books on Ronald Reagan, most recently “Reagan Rising.” He has a political biography of Newt Gingrich, “Citizen Newt,” coming out August 29, 2017.

Scott Mauer is Craig Shirley’s researcher. Previously, he had presented and guest-lectured on Soviet and Russian history, as well as other works specializing in Eastern European events. He earned his Master of Arts in History from Hood College in Frederick, Maryland.