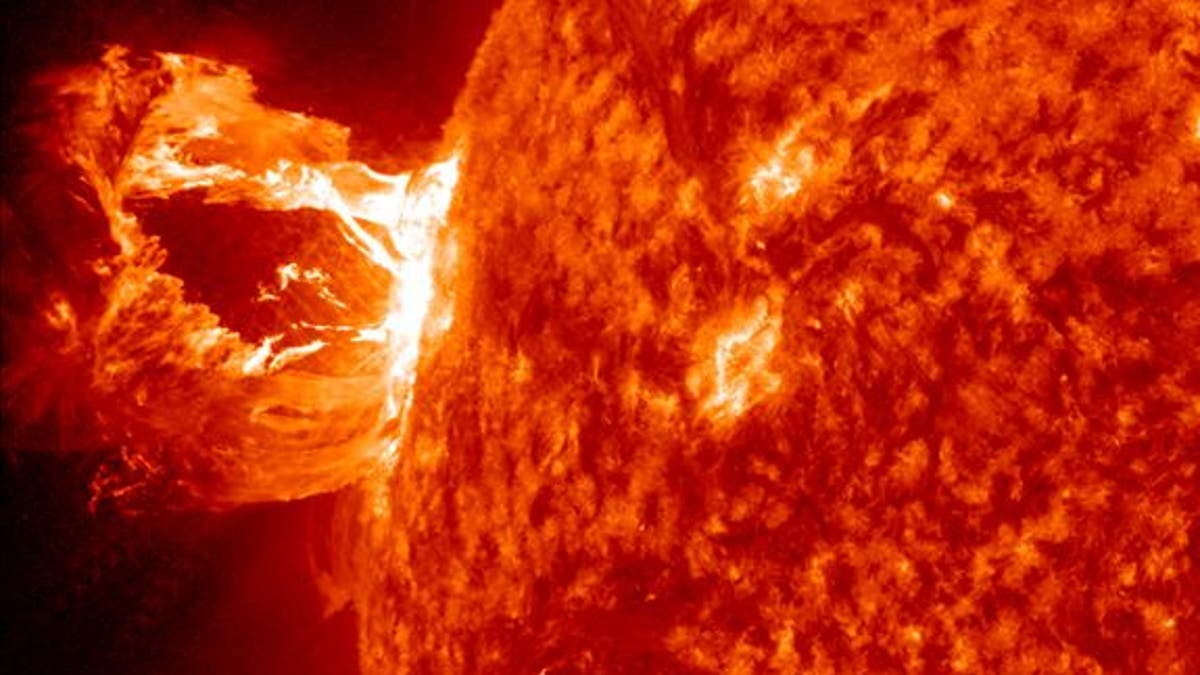

April 16, 2012: A beautiful solar prominence erupts off the east limb (left side) of the sun. This view of the flare was recorded by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory. (NASA/GSFC/SDOA)

Humanity needs to be much better prepared for massive solar storms, which can wreak havoc on our technology-dependent society, a prominent researcher warns.

Powerful blasts from the sun have triggered intense geomagnetic storms on Earth before, and they'll do so again. But at the moment our ability to predict these events and guard against their worst consequences — which can include interruptions of power grids and satellite navigation systems — is lacking, says Mike Hapgood of the British research and technology agency RAL Space.

"We need a much better understanding of the likelihood of space weather disruptions and their impacts, and we need to develop that knowledge quickly," Hapgood, head of RAL Space's space environment group, writes in a commentary in the April 19 issue of the journal Nature.

Potentially devastating storms

The solar storms we need to worry about, Hapgood says, are coronal mass ejections, huge clouds of charged solar plasma that can rocket into space at speeds of 3 million mph (5 million kilometers per hour) or more.

CMEs that hit Earth inject large amounts of energy into the planet's magnetic field, spawning potentially devastating geomagnetic storms that can disrupt GPS signals, radio communications and power grids for days. [The Worst Solar Storms in History]

[pullquote]

The world witnessed such effects not too long ago. In March 1989, a CME caused a power blackout in Quebec, leaving 5 million Canadians in the dark in cold weather for hours. The event caused about $2 billion in damages and lost business, Hapgood writes.

But CMEs are capable of much greater mischief. A huge ejection — now known as the Carrington event, after a British astronomer— slammed into Earth in 1859, setting off fires in telegraph offices. The world was not technologically advanced enough yet to suffer worse consequences, Hapgood noted.

"If we had a repeat of the Carrington event, I would expect several days of economic and social mayhem as many critical technological systems failed – e.g., localized power grid failures in many countries, widespread loss of GPS signals for navigation and timing, disruption of communications systems, shutdown of long-haul aviation," Hapgood told SPACE.com via email.

And the short-term problems caused by such a storm could pale in comparison with its long-term impact, he added.

"What scares me is the possibility that this recovery could take a long time in many parts of the world," Hapgood said. "Over the past few decades, we have become much more dependent on technology to sustain our everyday lives: e.g., electricity to pump clean water to our homes and remove sewage, just-in-time supply chains to feed us, ATMs and retail card readers to provide money for everyday shopping. Do we know how to recover quickly from the simultaneous disruption of a huge range of systems?"

Improving predictions

Despite a growing sense of concern among scientists — and decision-makers in politics and industry — our technology-dependent society remains vulnerable to a big CME-spawned geomagnetic storm, Hapgood says. [Photos: Huge Solar Flare Eruptions of 2012]

For starters, our forecasting ability, while improving, is still lacking. The United States' Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) can currently provide warnings of strong geomagnetic storms 10 to 60 minutes in advance with about 50 percent accuracy, Hapgood writes. That's a pretty small window for power companies to take protective measures.

SWPC scientists and other space-weather forecasters generally rely on observtions of approaching CMEs made by a handful of spacecraft. These include NASA's Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) and Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) probes, as well as the NASA/European Space Agency Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO).

ACE launched in 1997, SOHO in 1995 and the twin STEREO craft in 2006. It's time for an upgrade, Hapgood told SPACE.com.

"We really need to replace those spacecraft and their instruments that monitor CMEs and, if possible, upgrade the instruments so they are optimized for space weather monitoring – essentially to pull out the most critical data and get it back to Earth as soon as possible," he said.

Preparing for the worst

The 1989 event spurred some power companies to require that all new transformers be able to withstand storms of similar magnitude.

But Hapgood thinks power, aviation and other vulnerable industries — including finance, which depends on precise GPS time stamps for automatic trading — should take a longer view and guard against the huge storm that comes along just once every 1,000 years or so.

That's tough to do, since researchers don't know what a thousand-year storm might look like; data on such dramatic events are pretty hard to come by. But Hapgood says scientists could get a better idea by analyzing more data, including observations from a century or more ago.

Much of this historical information exists on paper only. Digitizing it would bring these records to the attention of many more researchers, Hapgood says, and he suggests enlisting citizen scientists to do the job on the Internet, much as the Galaxy Zoo project asks volunteers to classify galaxies online by the galaxies' shapes.

Researchers also need to develop better physics-based models to improve their understanding of extreme space weather, Hapgood says. And he suggests that studying storms on other, sunlike stars could be helpful, too.

In general, Hapgood is calling for powerful geomagnetic storms to be regarded as natural hazards similar to big earthquakes and volcanic eruptions: infrequent, potentially devastating events.

"These events often transcend the experience of any individual because they happen so rarely. Thus there is an all-too-human tendency to ignore them — that they lie outside the awareness of the decision-maker and probably will not occur during his term of office," Hapgood said. "But these events will happen sometime. We need to understand them and decide how far we should (i.e., can afford to) protect against them — and definitely not leave them until it's too late."