Fox News Flash top headlines for August 9

Fox News Flash top headlines for August 9 are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com

The company that operates Fukushima's tsunami-devastated nuclear power plant said on Friday it will run out of space to store radioactive water within three years. Worries are intensifying on what will become of the water and whether a consensus can be reached in time.

Following a massive earthquake in 2011, three reactors at the Fukushima Dai-ichi plant suffered meltdowns, causing radioactive water to leak from the reactors and mix with the groundwater and rainwater at the plant. The water is being treated but is still slightly radioactive and is stored in 1,000 large tanks, which hold 1 million tons of water.

Tokyo Electric Power Co. (TEPCO), which operates the plant, said it will build more tanks, but can only accommodate an additional 1.37 million tons, a level that will be reached by the summer of 2022, two years after the country hosts the Summer Olympics.

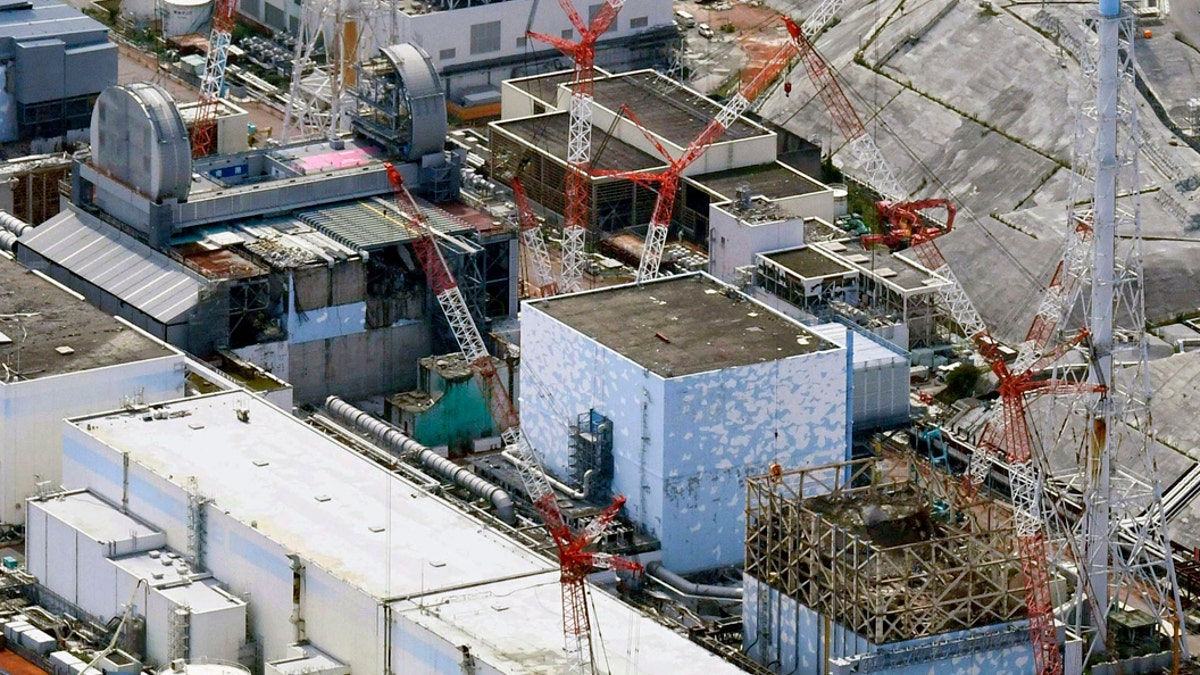

FILE - This Sept. 4, 2017, aerial file photo shows Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant reactors, bottom from right, Unit 1, Unit 2 and Unit 3, in Okuma town, Fukushima prefecture, northeastern Japan. The utility company operating Fukushima's tsunami-wrecked nuclear power plant said Friday, Aug. 9, 2019 it will run out of space for tanks to store massive amounts of treated but still contaminated water in three years, adding pressure for the government and the public to reach consensus on what to do with the water. (Daisuke Suzuki/Kyodo News via AP, File)

Nearly 9 years since the accident, officials have yet to agree on what to do with the radioactive water. A government-commissioned panel has picked five alternatives, including the controlled release of the water into the Pacific Ocean, which nuclear experts, including members of the International Atomic Energy Agency, say is the only realistic option. Fishermen and residents, however, strongly oppose the proposal, saying the release would be suicide for Fukushima's fishing and agriculture.

Experts say the tanks pose flooding and radiation risks and hamper decommissioning efforts at the plant. TEPCO and government officials plan to start removing the melted fuel in 2021, and want to free up part of the complex currently occupied with tanks to build safe storage facilities for melted debris and other contaminants that will come out.

In addition to four other options including underground injection and vaporization, the panel on Friday added long-term storage as a sixth option to consider.

Several members of the panel urged TEPCO to consider securing additional land to build more tanks in case a consensus cannot be reached relatively soon.

TEPCO spokesman Junichi Matsumoto said contaminants from the decommissioning work should stay in the plant complex. He said long-term storage would gradually reduce the radiation because of its half-life, but would delay decommissioning work because the necessary facilities cannot be built until the tanks are removed.

Matsumoto declined to specify the deadline for a decision on what to do with the water but said he hopes to see the government lead public debate.

In April, TEPCO said that workers had started to remove the first of 566 fuel units in the pool at Unit 3, a process that will take three years. The other two reactors will follow once that is done, a process that take upwards of a decade as the plant is eventually decommissioned.

As of February 2017, the government counted 2,129 "disaster-related deaths" from the tsunami, including deaths related to stress, suicide and the interruption of medical care. It wasn't until September 2018 when the Japanese government officially acknowledged the first death due to radiation.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

The Associated Press contributed to this report.