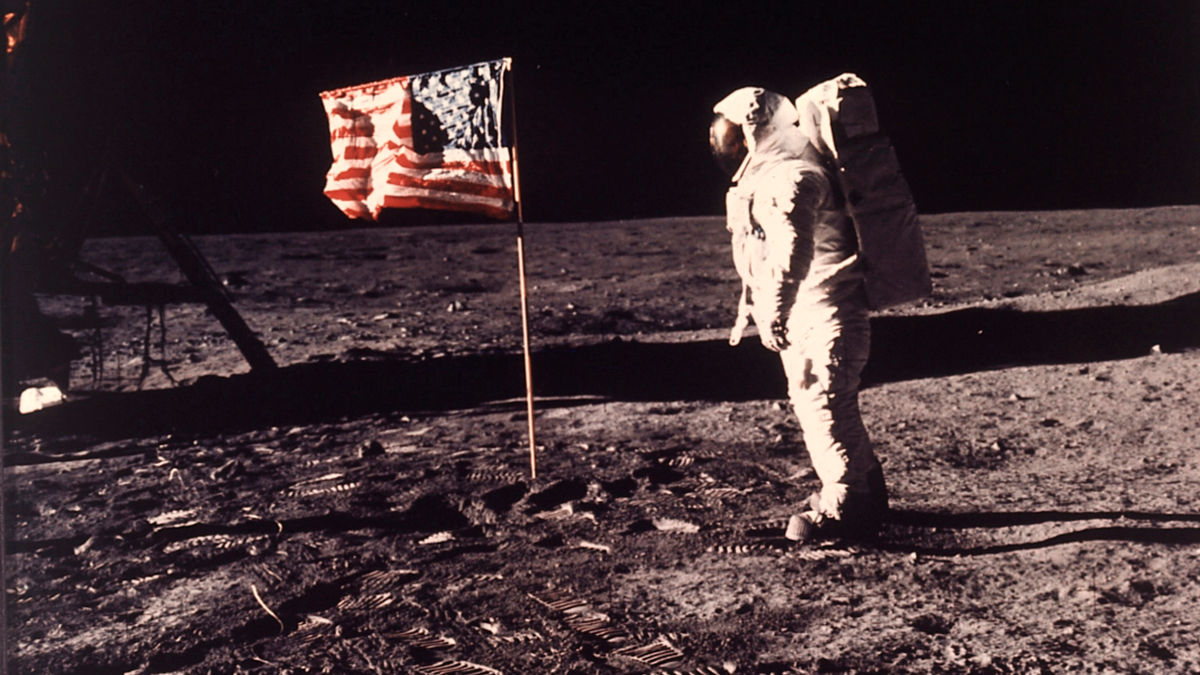

FILE - In this image provided by NASA, astronaut Buzz Aldrin poses for a photograph beside the U.S. flag deployed on the moon during the Apollo 11 mission on July 20, 1969. (Neil A. Armstrong/NASA via AP, File)

More than 413,000 pounds: That’s the estimated total weight of all man-made items left on the moon since Apollo 11 astronauts became the first to land there in 1969. This “lunar litter,” as documentary filmmaker Arlen Parsa called it in his 2012 short film, is itemized in a 22-page document from NASA. Here, highlights of detritus discarded during five decades of visits:

Six flags

Apollo 11, 12, 14, 15, 16 and 17, the manned missions that successfully landed on the moon between 1969 and 1972, all planted American flags in lunar soil. Five of them are still standing, according to Mark Robinson, a professor at Arizona State University and is the principal investigator for the NASA Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera, which has monitored all the flags and captured photos. “[The] Apollo 11 flag fell over when the ascent stage blasted off,” Robinson says. As for the five star-spangled banners still upright, Robinson added, they’re almost certainly bleached by the atmosphere’s UV rays. “I can say that the flags have very likely suffered fading from ultraviolet light exposure,” he adds. “Since there is no record of the material the flags were made of one can only speculate as to the degree of fading and any other damage.”

Disc of goodwill messages

Apollo 11 carried a tiny cylindrical case made of silicon containing a scroll with greetings from the leaders of 73 countries (including two countries, Yugoslavia and the Republic of Dahomey, that don’t exist today). Given that the whole package was the size of a half-dollar, the text inside the disc was scanned and reduced 200x, so it could only be read with a magnifying glass. The disc, whose outside reads “From Planet Earth — July 1969,” still sits in the moon’s Sea of Tranquility after being tossed there by Buzz Aldrin.

Olive branch

Less than 6 inches long, the golden trinket was left by the Apollo 11 astronauts as “a wish for peace for all mankind,” according to NASA.

Golf balls

During his 1971 moonwalk, Apollo 14 astronaut Alan Shepard withdrew a six-iron to drive two golf balls into the lunar landscape. Granted, he did it awkwardly, given the bulky, stiff spacesuit. Thanks to the low gravity, however, even his second rough shot went 200 yards. The cute stunt apparently took mission controllers in Houston by surprise; Shepard had smuggled the golf club in his suit. He brought the club back to Earth; it’s in the United States Golf Association Museum.

Astronaut badge

When Alan Bean walked on the moon during Apollo 12’s visit in 1969, he removed his silver lapel pin, which depicted a shooting star with an orbit around its tail, and tossed it into the unknown. “I can still remember how it flashed in the bright sunlight then disappeared in the distance. It was the only star I ever saw up in the black sky, the sunlight was just too bright on the Moon’s surface to see any of the others,” the late Bean described about a work of art he painted of the scene. “I often think of my silver pin resting in the dust of Surveyor Crater, just as bright and shiny as it ever was. It’ll be there for millions and millions of years or until some tourist finds it and brings it back to Earth.”

A bible

The commander of 1971’s Apollo 15, David Scott, put a paper copy of the holy book with a red cover on the dashboard of an abandoned lunar roving vehicle.

Fallen astronaut sculpture

Scott also left a 3.3-inch silver statuette by Belgian artist Paul Van Hoeydonck next to a plaque with the names of the 14 space explorers from the US and the Soviet who had died up until that point.

Astronaut excrement

The 22-page NASA document lists “defecation collection devices” (five) and “urine collection assemblies” (seven) and “urine receptacle systems” (three). Our heroic lunar explorers were indeed still humans who excreted bodily waste on the flights up that required disposal before any return trips.

Five retroreflectors

In order to calculate the distance between the Earth and the moon with great precision, observatories from California to France to Tokyo aim laser beams at mirrored surfaces placed on the lunar surface — first by Apollo 11 (1969), and later by Apollo 14 and 15 (1971) and the Soviet Union’s Luna 17 (1970) and 21 (1973). Researchers can deduce the distance at any point in the orbit — which can range from about 225,000 to 252,000 miles between the Earth and its satellite — by measuring the time it takes for the laser beams to reach the moon and then return to Earth.

Crafts, crashes and rovers

In addition to tools used for various equipment — video footage from 1972’s Apollo 17 shows Jack Schmitt imploring Houston, “Let me throw the hammer. Let me throw the hammer!” — there are more than 80 different partial or whole spacecrafts, rockets, surveyors, orbiters and vehicles. They arrived on the moon from the US and the Soviet Union, yes, but also India, China, Israel, Japan and Europe. Much of this machinery crashed on the lunar service and are not operational. But two crafts have landed on the moon in 2019, and one of those, the Chang’e 4 lander from China, is still working.

This story originally appeared in the New York Post.