Fox News Flash top headlines for May 8

Fox News Flash top headlines for May 8 are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com

Plastic pollution in the world's oceans may have a $2.5 trillion impact, negatively affecting "almost all marine ecosystem services," including areas such as fisheries, recreation and heritage. But a breakthrough from scientists at Berkeley Lab could be the solution the planet needs for this eye-opening problem – recyclable plastics.

The study, published in Nature Chemistry, details how the researchers were able to discover a new way to assemble the plastics and reuse them "into new materials of any color, shape, or form."

“Most plastics were never made to be recycled,” said lead author Peter Christensen, a postdoctoral researcher at Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Foundry, in the statement. “But we have discovered a new way to assemble plastics that takes recycling into consideration from a molecular perspective.”

PLASTIC POLLUTION IN WORLDS' OCEANS COULD HAVE $2.5 TRILLION IMPACT, STUDY SAYS

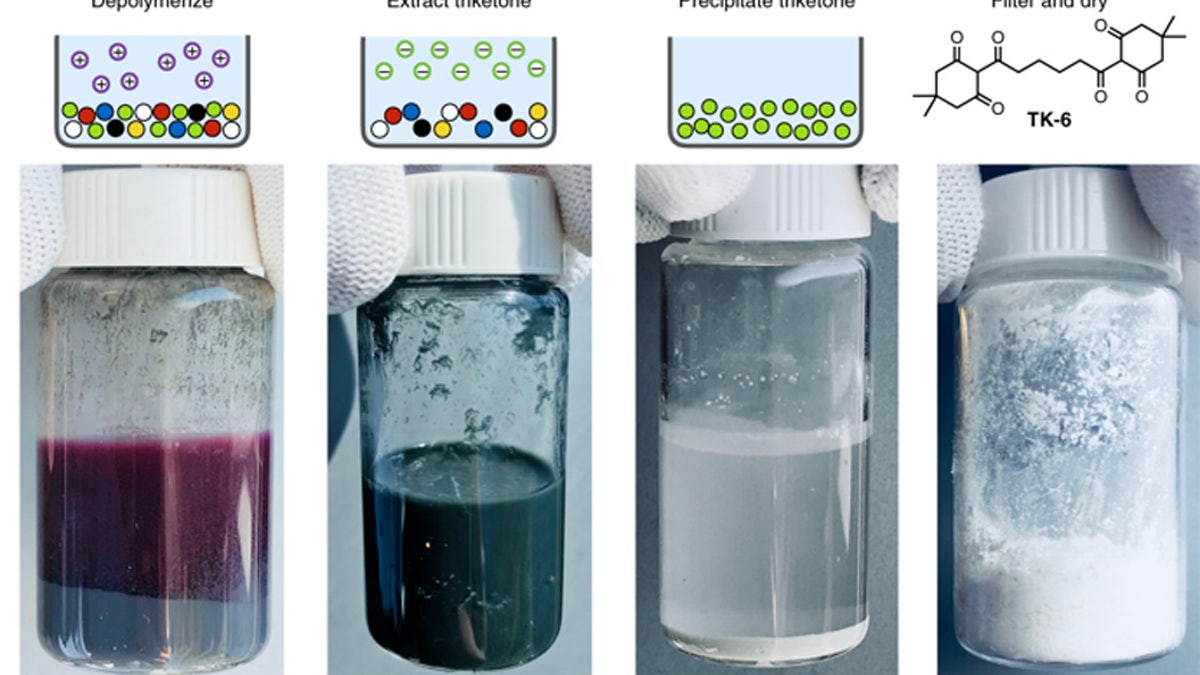

Known as poly(diketoenamine), or PDK, the new type of plastic material could help stem the tide of plastics piling up at recycling plants, as the bonds PDK forms are able to be reversed via a simple acid bath, the researchers believe.

"Poly(diketoenamine)s ‘click’ together from a wide variety of triketones and aromatic or aliphatic amines, yielding only water as a by-product," the study's abstract reads. "Recovered monomers can be re-manufactured into the same polymer formulation, without loss of performance, as well as other polymer formulations with differentiated properties. The ease with which poly(diketoenamine)s can be manufactured, used, recycled and re-used—without losing value—points to new directions in designing sustainable polymers with minimal environmental impact."

Unlike conventional plastics, the monomers of PDK plastic could be recovered and freed from any compounded additives simply by dunking the material in a highly acidic solution. (Credit: Peter Christensen et al./Berkeley Lab)

A byproduct of petroleum, plastic is inherently made up of molecules known as polymers that are composed of carbon-containing compounds known as monomers. Once chemicals are added to the plastic for use and consumption, the monomers bind with the chemicals and make it difficult to be processed at recycling plants, the researchers said.

When the plastics are chopped up in an effort to make new products, it's difficult to predict "which properties it will inherit from the original plastics," the researchers added.

Prior to the discovery, the unpredictableness of the properties had made it nearly impossible to perform what has been coined "the Holy Grail of recycling:" a "circular" material that can be used over and over again for any number of products, including adhesives, phone cases, computer cables and more.

“Circular plastics and plastics upcycling are grand challenges,” said Brett Helms, a staff scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Foundry, in the statement. “We’ve already seen the impact of plastic waste leaking into our aquatic ecosystems, and this trend is likely to be exacerbated by the increasing amounts of plastics being manufactured and the downstream pressure it places on our municipal recycling infrastructure.”

This time-lapse video shows a piece of PDK plastic in acid as it degrades to its molecular building blocks – monomers. The acid helps to break the bonds between the monomers and separate them from the chemical additives that give plastic its look and feel. (Credit: Peter Christensen/ Berkeley Lab)

Though PDK only exists in the lab currently (meaning products won't be available for purchase for some time), the researchers are nonetheless excited by what they've discovered and the potential positive impact it could have.

“With PDKs, the immutable bonds of conventional plastics are replaced with reversible bonds that allow the plastic to be recycled more effectively,” Helms added. "We’re interested in the chemistry that redirects plastic lifecycles from linear to circular. We see an opportunity to make a difference for where there are no recycling options.”

MELTING PERMAFROST IN ARCTIC WILL HAVE $70 TRILLION IMPACT, NEW STUDY SAYS

Plastic reuse

Plastic recycling figures are trending down, making breakthroughs in recyclable plastic all the more important. According to the latest publicly available data, only 9.1 percent of the plastic created in the U.S. in 2015 was recycled, down from 9.5 percent in 2014, according to the EPA.

Last month, a separate study estimated that the pollution caused by plastics in the world's oceans amounted to a $2.5 trillion problem that every country in the world has to deal with. The estimate did not take into account the impact on sectors of the global economy such as tourism, transport, fisheries and human health, the researchers wrote.

"An ecosystem impact analysis demonstrates that there is global evidence of impact with medium to high frequency on all subjects, with a medium to high degree of irreversibility," the study's abstract reads, with the researchers adding that they looked at nearly 1,200 data points to come up with their conclusions.

PREGNANT WHALE FOUND DEAD IN ITALY WITH 49 POUNDS OF PLASTIC IN STOMACH

Despite several efforts of countries around the world to reduce or stop the use of plastic altogether, the amount of plastic in the world's oceans is increasing, and spreading across the planet.

A separate study, published in Nature on April 16, is the first study "to confirm a significant increase in open ocean plastics in recent decades," going back nearly 60 years. Researchers found a plastic bag that had been snared on Ireland's coast since 1965 and is possibly the first piece of plastic pollution ever found, according to the BBC.

That study was based off a 2015 investigation that estimated there were between 4.8 trillion and 12.7 trillion pieces of plastic entering the ocean every year.