Fox News Flash top headlines for October 19

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

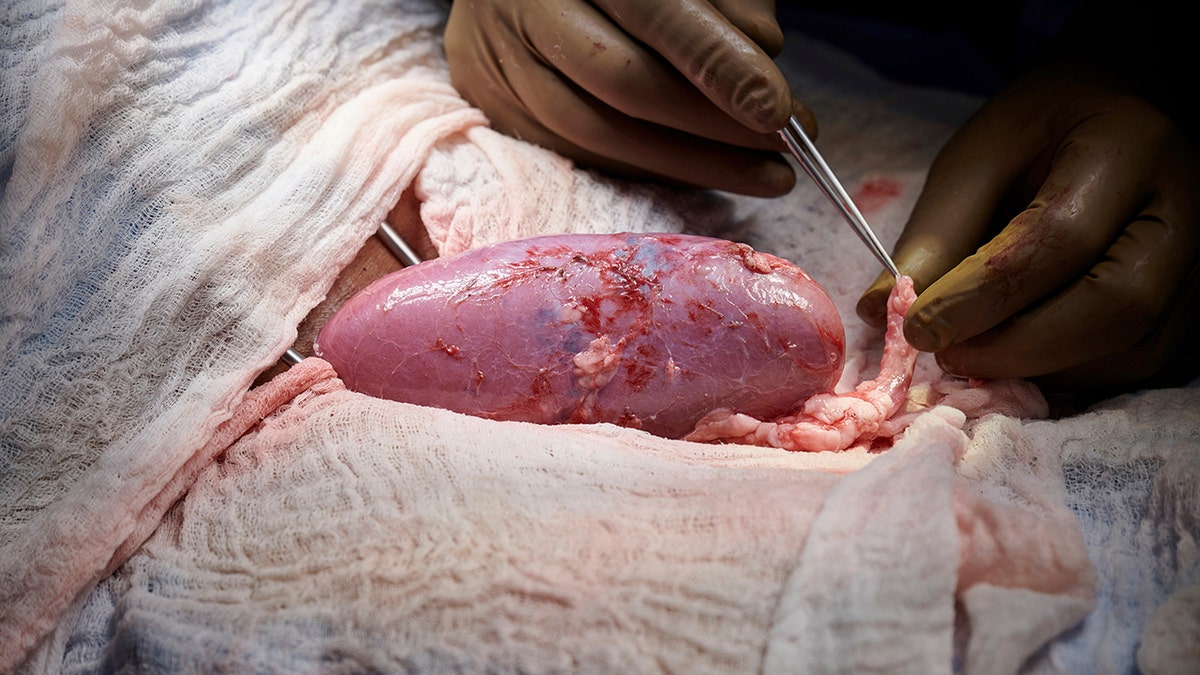

A pig kidney was successfully tested on a dead patient at a hospital in New York last month for the first time without being immediately rejected.

While pig organs are similar to human ones, a sugar in pig cells triggers organ rejection.

GRAPHIC SURGICAL IMAGE BELOW

"It had absolutely normal function," said Dr. Robert Montgomery, who led the surgical team at NYU Langone Health. "It didn’t have this immediate rejection that we have worried about."

Researchers have turned to pigs to help with the kidney donor shortage. Around 12 patients die a day waiting for a kidney.

The pig came from Revivicor, a biotech company that engineers the animals to edit out the sugar gene. The company has a herd of 100 pigs at a facility in Iowa.

The gene alteration was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration last December as safe for human food consumption and medicine. But the FDA said developers would need to submit more paperwork before pig organs could be transplanted into living humans.

In this September 2021 photo provided by NYU Langone Health, a surgical team at the hospital in New York examines a pig kidney attached to the body of a deceased recipient for any signs of rejection. (Joe Carrotta/NYU Langone Health via AP) (Joe Carrotta/NYU Langone Health via AP)

"This is an important step forward in realizing the promise of xenotransplantation, which will save thousands of lives each year in the not-too-distant future," said United Therapeutics CEO Martine Rothblatt in a statement. Revivicor is a subsidiary.

ORGAN TRANSPLANTS SAW MARKED DECLINE WORLDWIDE AMID PANDEMIC: STUDY

The kidney was tested on the patient for two days during which it worked properly, filtering waste and producing urine.

This undated photo provided by Revivicor in December 2020 shows a "GalSafe" pig which was genetically engineered to eliminate a sugar in pig cells, foreign to the human body, which causes immediate organ rejection. Scientists temporarily attached kidney from one of these pigs to a human body and watched it begin to work, a small step in the decades-long quest to one day use animal organs for life-saving transplants. (Revivicor via AP) (Revivicor via AP)

Researchers kept the woman’s’ body on a ventilator during the experiment with her family’s consent.

Some animal rights advocates question the ethics of raising pigs for organ donation but others note that pigs are already raised for food unlike primates, which were used in some transplant experiments in the 20th century. Pigs also have large litters and short gestation periods. Pig heart valves and skin for burn victims are already used for humans.

In this September 2021 photo provided by NYU Langone Health, a surgical team at the hospital in New York examines a pig kidney attached to the body of a deceased recipient for any signs of rejection. The test was a step in the decades-long quest to one day use animal organs for life-saving transplants. (Joe Carrotta/NYU Langone Health via AP) ((Joe Carrotta/NYU Langone Health via AP)

"The other issue is going to be: Should we be doing this just because we can?" Karen Maschke, a research scholar at the Hastings Center, who will help develop ethics and policy recommendations for the first clinical trials under a grant from the National Institutes of Health, said.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Besides Revivicor, other biotech companies are also looking to develop pig organs for humans.

Pig transplants into living patients could come in the next few years, experts say.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.