KANSAS CITY, Mo. – Two Kansas City teenagers walking along a dry creek bed in northern Kansas City have found what a forensic anthropologist says is the skull of an American Indian woman who likely died centuries ago.

Hunter Collins, 15, and his girlfriend, Heather Johnson, 17, thought they had found some dead animal bones when they spotted the skull Jan. 28. But then Heather gathered up four pieces of the half skull and fit them together. They also poked around the mud with a stick and found a tooth, The Kansas City Star reported.

[pullquote]

"When I first saw it and realized what it was, I was scared," said Heather, a junior at North Kansas City High School. She thought perhaps someone had been murdered.

The teens alerted a security guard at a nearby business. When police arrived they also thought they might have a homicide on their hands, in part because the skull had a hole that looked like it could have been from a bullet.

"We started ramping up, thinking we may be working a serious investigation," police Maj. Steve Beamer said.

The skull and the tooth were sent to the Jackson County medical examiner's office, which shipped them to a forensic anthropologist in Manhattan, Kan., to see if the skull belonged to a homicide victim, Beamer said.

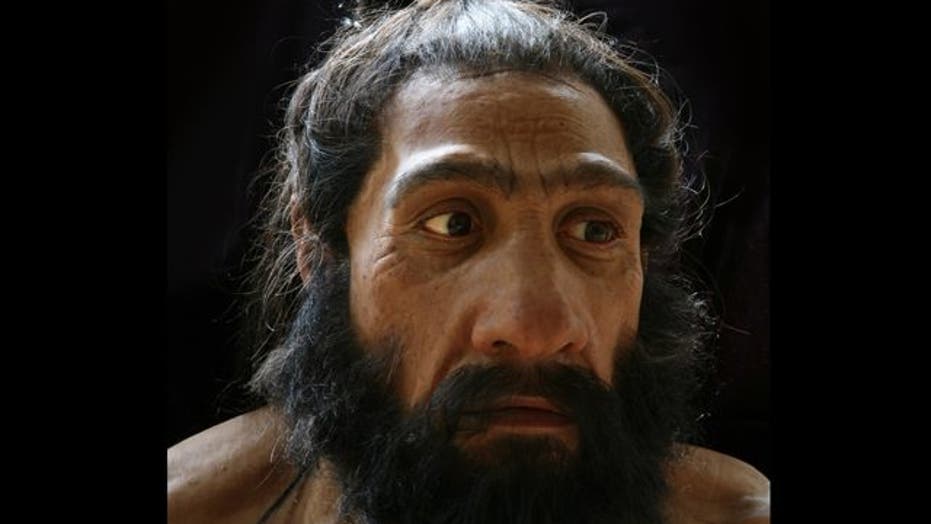

Three days later, Michael Finnegan, who teaches anthropology at Kansas State University, told authorities there was no crime and that the skull belonged to a mongoloid female of a historic or prehistoric era. He said the puncture on the top of the skull likely happened after she died.

"The tooth displays a wear pattern consistent with earlier human populations (American Indian)," Finnegan reported.

The skull will be sent to the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, which plans to place it in the secure room at the Rock Bridge Curation facility at Rock Bridge Memorial State Park near Columbia, department spokeswoman Steph Reed said. Such artifacts are protected through the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. As a show of respect to the culture, no photographs are being allowed.

State officials eventually will send a report to Indian tribes associated with Missouri. Reed said the remains will be held until one of the tribes formally requests possession of it. The work of the medical examiner and forensic anthropologist was also sufficient in identifying the remains as of American Indian origin, and there are no further plans to identify the skull, Reed said.