(Wikimedia)

Syrian rebels and government officials have accused each other of launching chemical attacks -- an escalation that, if confirmed, would mark the first known use of chemical weapons in the civil war.

U.S. officials downplayed the allegations and said they could find no evidence of such weapons.

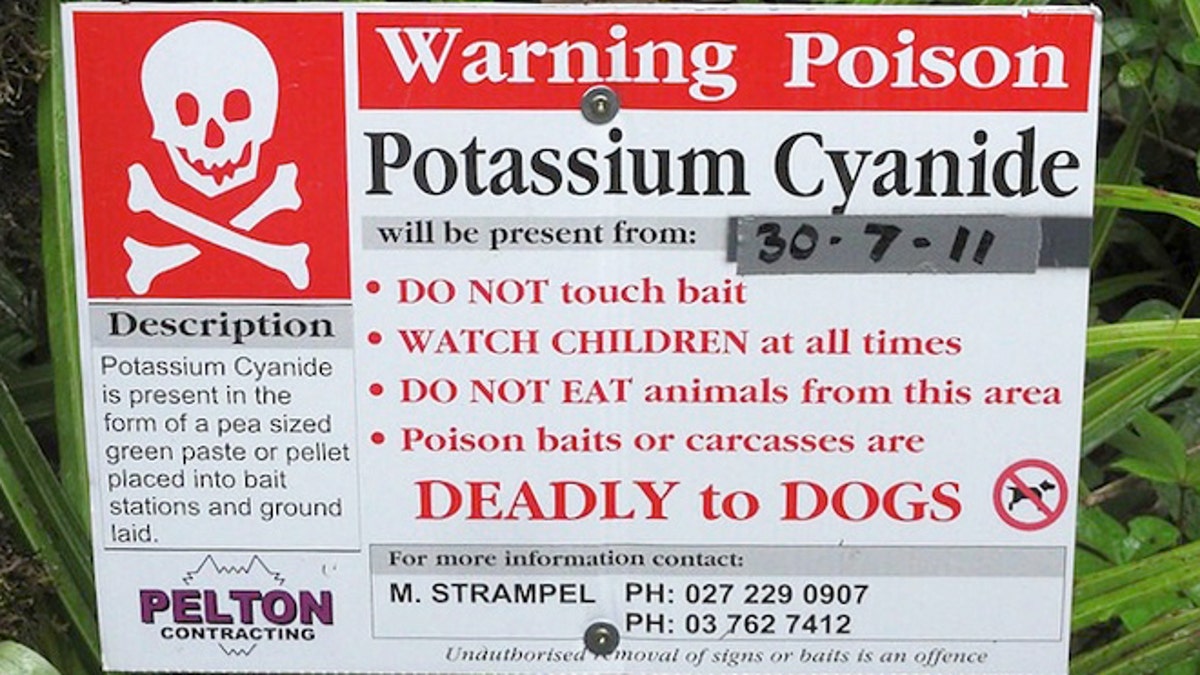

Chemical weapons like anthrax, sarin, mustard and ricin often make headlines, but what about the threat of a terrorist attack unleashing cyanide? Some security experts believe the gas threat is real -- and this particular poison acts very fast, making it particularly challenging for first responders.

Fortunately, a new antidote holds promise.

The current treatment for cyanide must be administered by IV or intravenous infusion, a procedure that is time-intensive and requires highly trained paramedical personnel.

- South Korean banks and media report computer network crash, causing speculation of North Korea cyberattack

- How drones teach kids science & math

- MALE drones needed now to fly solo in hot spots

- A spy at NASA? FBI investigating Chinese man arrested fleeing country

- Rules for hackers: Cyberwar manual applies international law to the field of online attacks

All this stacks up to an ugly fact: in a mass casualty situation, only a limited number of victims could be saved.

“There is no effective cyanide antidote that can be administered rapidly,” said Steve Patterson, co-inventor and associate director of the university’s Center for Drug Design, where Sulfanegen was invented. “In the case of a mass casualty situation, the emergency responders wouldn’t be able to treat most of the victims.”

The latest episode in the American Chemical Society’s Global Challenges/Chemistry Solutions podcast series brings very good news for this threat: A new antidote that may help seal off this gap in national defense.

Research undertaken by Steven E. Patterson, Ph.D., of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Drug Design and colleagues has discovered a promising new alternative antidote. And this antidote could be self-administered, sort of like the average allergy injection pens that many small children carry with them to school.

The new substance, called sulfanegen TEA, could be administered as intra-muscular injection.

Using a simpler procedure means a far larger number of cyanide victims in a mass casualty incident could be rapidly treated. Patterson’s report appears in ACS' Journal of Medicinal Chemistry.

The drug will be produced by a new startup called Vytacera, pending FDA approval.

“We intend to move forward as rapidly as financing and regulations permit,” added Jon S. Saxe, chair of Vytacera. “Our goal is to make this important advance available to those in need of it and to enable governments to be better prepared, which, ultimately, may help deter terrorism.”

Ballet dancer turned defense specialist Allison Barrie has traveled around the world covering the military, terrorism, weapons advancements and life on the front line. You can reach her at wargames@foxnews.com or follow her on Twitter @Allison_Barrie.