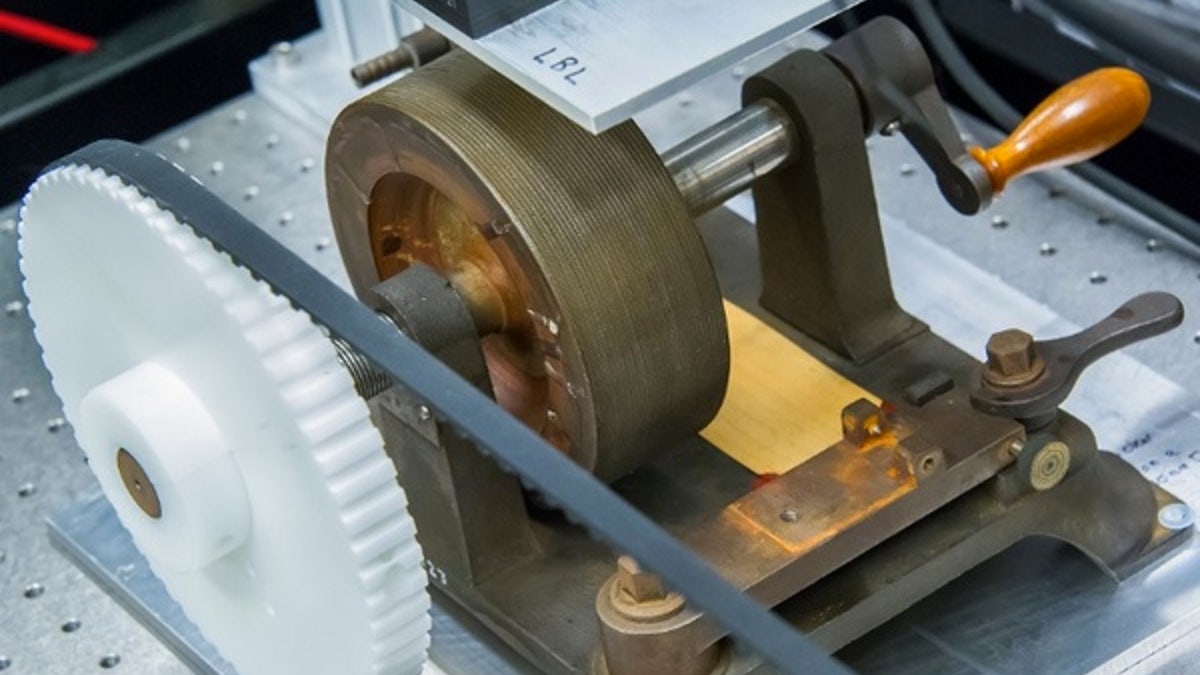

A voice recording of Alexander Graham Bell’s father was recovered on this wax-coated drum, which was shipped to Berkeley Lab earlier this year for analysis. (Credit: Roy Kaltschmidt)

The quality is rough, like the way radios sound in old movies. But the voice is strong, and the note of barely contained joy in the solemn pronouncement is impossible to miss: “In witness whereof, hear my voice, Alexander Graham Bell.”

So intoned the inventor of the telephone in 1885.

[pullquote]

He recorded his voice on a simple disc made from wax and paperboard. For years that disc lay silent and gathering dust, first at his Washington, D.C. laboratory, and then in the Smithsonian Museum’s archives.

But researchers have taken these old discs, too fragile to spin on a gramophone anymore, and digitally extracted the audio. Now, thanks to Berkeley Labs’ Carl Haber and Earl Cornell, as well as the Library of Congress and Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, Bell’s sound waves are back in the air, this time coming from computer speakers.

To achieve this, the researchers created a high-resolution digital map of the decrepit disc’s recording surface using a scanner that was first developed for particle physics experiments. From this map, the researchers could then tweak the data to minimize white noise and amplify the voices, and now you can listen to the result on YouTube.

"Identifying the voice of Alexander Graham Bell — the man who brought us everyone else's voice — is a major moment in the study of history," said Smithsonian museum director John Gray in a press release, pointing out that not only can researchers now precisely identify Bell's voice, but they can also use Bell's recordings to study speech patterns and affects of late nineteenth century America.

Aside from Bell himself, the researchers have identified several other people on the other recordings, including the inventor’s father Alexander Melville Bell.

The elder Bell is obviously thrilled with the technology that made his son famous. On one of the recordings he can be heard quoting Hamlet: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in our philosophy,” and offering a Monty Python-esque meditation on technological evolution: “I am a gramophone, and my mother was a phonograph.”