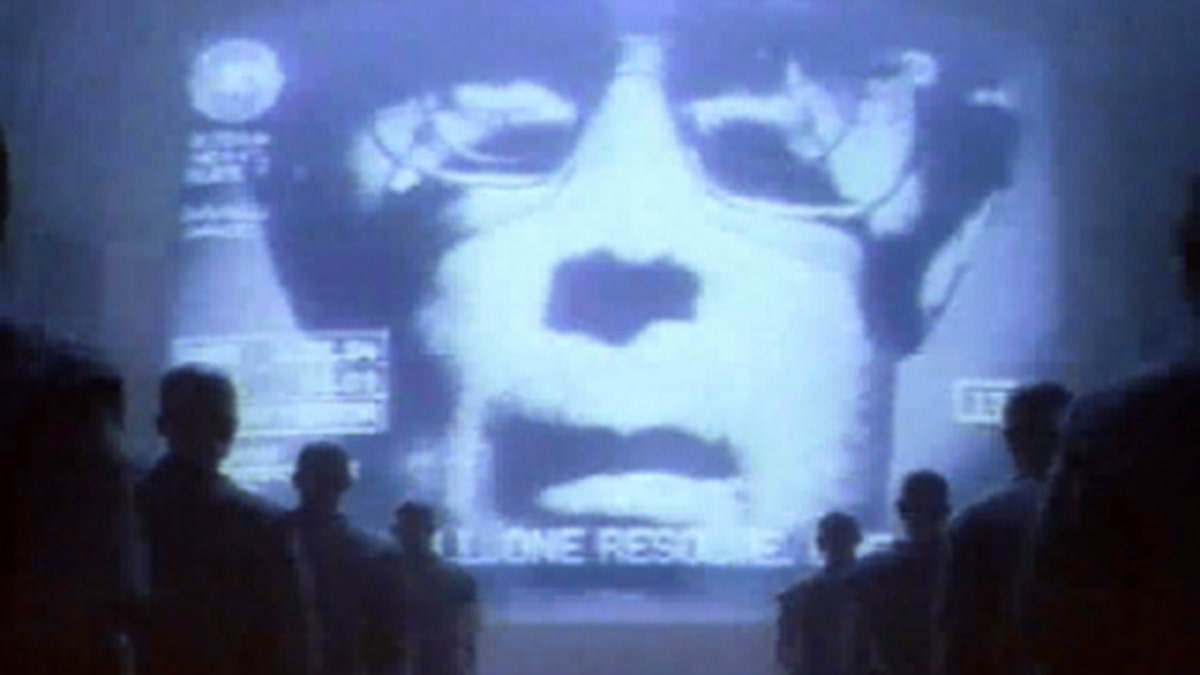

Apple's "1984" commercial depicted Windows-based computer makers as Big Brother. But a new copyright-control law may be turning your ISP into Big Brother instead. (Apple)

I know people who do it. You probably know people who do it. And we're not talking about falling in love.

File sharing, the euphemism for copying and sharing copyrighted material without paying, was one of the early hallmarks of the digital, anything-goes-on-the-Internet age. Names like Napster became synonymous with killing the music industry. And there were countless lawsuits against groups and individuals aimed at curbing illegal sharing -- but nothing seemed to work.

Now, the concern is that the same fate will befall the movie business. With higher speed networks, it's nearly as easy to share "Argo" as it is to share Adele. And everything is connect to the Web, from phones to TVs, so the movie and TV companies and individual content creators are worried.

So a new industry initiative has been launched that may turn your Internet service provider (ISP) into the unofficial Web police, curbing access for perceived abusers and forcing offenders to take remedial courses in copyright rules.

A new industry initiative may turn your ISP into unofficial Web police, curbing access for perceived abusers and forcing offenders to take remedial courses in copyright rules.

Last week, the Copyright Alert System was officially launched. Created by the recording and film industry, it essentially deputizes copyright holders who stealthily monitor peer-to-peer networks for illegal sharing of movies, TV shows, and music. When they notice material is being illegally shared, they contact the crook's ISP, which in turn will send a warning message to the subscriber. After six strikes, the ISP will do more than spam you; it can choose to slow your access speed, temporarily downgrade you to a lower-tier service, or automatically direct you to a special landing page until you contact them or complete an online education program.

How can participating ISPs, which include AT&T, Cablevision, Comcast, Time Warner Cable and Verizon, be sure you're doing something illegal? The Center for Copyright Infringement says it has a “rigorous process” to make sure the content is illegal and they have a process for appealing alleged violations. But it will cost you $35, and there's no rule about how long an appeal will take (although you will get the money back if you win).

If this all sounds like something digital vilgilantism, it is.

Proponents, which include the Recording Industry Association of America and the Motion Picture Association of America, say its not about prosecution or persecution, it's about educating consumers. However, the Copyright Alert System seems like its waving a red flag in front of attorneys. Can you say, lawsuit?

Furthermore, the Alert system isn't likely to catch the big pirates and peer-to-peer provocateurs. Those people are sophisticated enough to use software that defeats online traces (or at least makes it incredibly difficult). Indeed, free programs like Tor that were created to protect political protesters and dissidents from persecution are often used by people looking to disguise their identities. In fact, Tor has become so popular with other criminal elements online that security firms today routinely tag such Tor traffic as spreading malware.

Perhaps a better solution to prevent illegal sharing would be to make it easier for consumers to rent or buy movies and shows. It has become easier, with services like Netflix and Hulu Plus, but it's still a fragmented market with wild price changes, confusion about digital purchases, and the persistence of “windows,” the term used in the business to describe staggered release dates (you can buy the DVD, but you can't rent it ... until later).

In fact, make it easier to follow the law, and people will generally give up the hassle of managing peer-to-peer networks and surreptitious downloads. At least, that seems to be the lesson learned in the music business.

Music revenues are up for the first time since 1999. A meager 0.3 percent in 2012 over the previous year to $16.5 billion, according to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, but it seems to show that the tide is turning. According to the NDP Group, the easy access of streaming services and readily available files for sale has meant that illegal sharing is down about 20 percent. Granted, no one in the music business is going to start partying like it's 1999. We're no where near sales like that, which amounted to $27.8 billion that year.

Sorting out the digital movie business is going to take time. Meanwhile, there's the Copyright Alert System. Well, at least they won't be suing moms for sharing copies of “Happy Birthday” online.

Follow John R. Quain on Twitter @jqontech or find more tech coverage at J-Q.com.