How DNA website helped crack Golden State Killer cold case

Investigators matched crime-scene DNA with genetic material put on genealogical site by a relative of Joseph James DeAngelo; senior correspondent Adam Housley reports from Los Angeles.

Investigators this week used a free genealogy website to help find the suspected Golden State Killer -- a celebrated development that nevertheless sparked questions about privacy concerns for those who use popular DNA-testing websites.

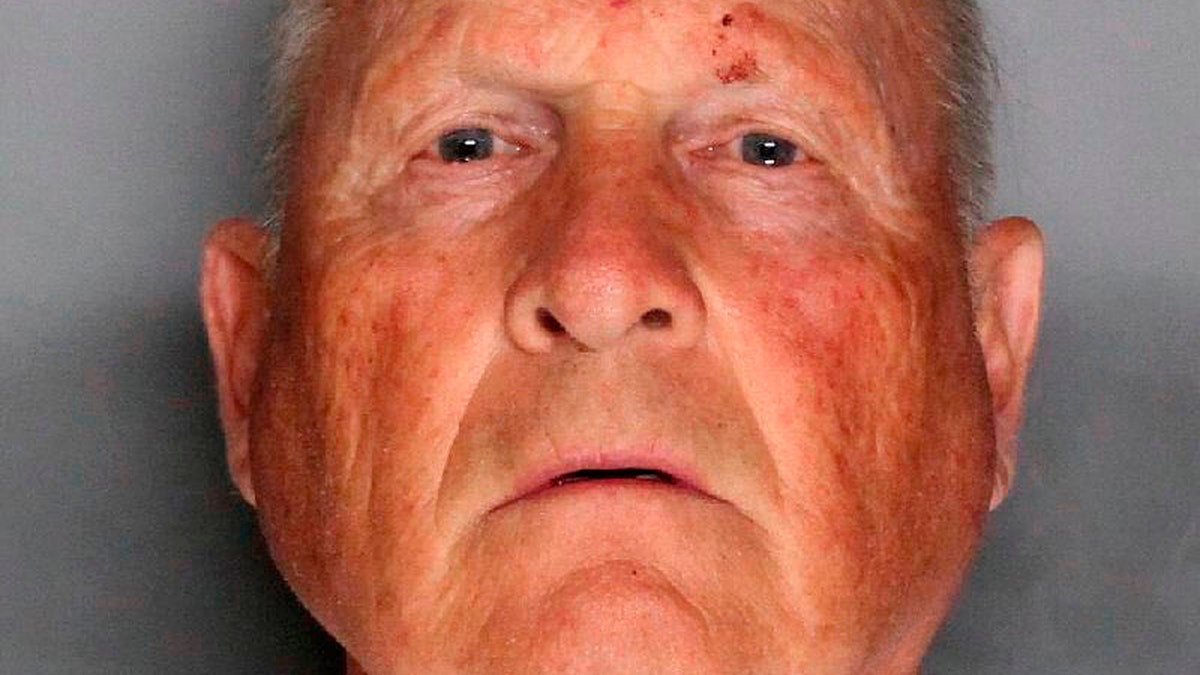

Joseph James DeAngelo, 72, was arrested after authorities matched DNA retrieved years ago from a crime scene linked to the so-called Golden State Killer and compared it to DNA samples from a family history website, the Sacramento County District Attorney’s Office said.

Investigators then obtained a direct DNA sample from the suspect after obtaining material he had discarded, Sacramento County Sheriff Scott Jones said.

Joseph James DeAngelo was arrested Tuesday in the Golden State Killer case. (Sacramento County Sheriff's Office via AP)

Authorities' biggest tools was GEDMatch, a Florida-based website that pools DNA profiles that people upload and share publicly, Paul Holes, one of the team’s top officials, told the Mercury News on Friday.

Holes said he didn’t need a search warrant to access the site’s database.

“GEDmatch exists to provide DNA and genealogy tools for comparison and research purposes,” the company says on its policy page. “It is supported entirely by users, volunteers, and researchers. DNA and Genealogical research, by its very nature, requires the sharing of information. Because of that, users participating in this site should expect that their information will be shared with other users."

But while investigators using DNA testing sites to blow open the Golden State Killer case may have brought a murderer to justice, it's also raising privacy concerns for the millions who submit their DNA to such sites to discover their heritage. Some observers say prospective users may be wary about using these testing programs in the future.

Sacramento County Sheriff Scott Jones talks to reporters on Wednesday about the arrest of Joseph James DeAngelo. (AP)

“Are you willing to have your DNA searched?” John Roman, senior fellow of economics, justice and society at NORC at the University of Chicago, told Fox News on Friday, adding it's still unclear how many samples authorities went through to find the link that led them to DeAngelo.

Major DNA ancestry websites such as Ancestry.com and 23andMe don’t allow law enforcement access to their profiles without a court order.

But the privacy laws keeping police from going through ancestry site databases aren’t strong, said Steve Mercer, the chief attorney for the forensic division of the Maryland Office of the Public Defender.

“People who submit DNA for ancestors testing are unwittingly becoming genetic informants on their innocent family,” Mercer said, adding users “have fewer privacy protections than convicted offenders whose DNA is contained in regulated databanks.”

DNA database inquiries are usually limited to those people who have been arrested or convicted criminals, according to the Bee. California legalized familial DNA testing in 2008, but it comes with restrictions. Searches can only be requested when authorities have a suspect and DNA is only allowed to be tested against databases that have samples from those arrested or who have been convicted.

The FBI maintains the DNA database system, but each state manages its own database. California passed a law in 2004 allowing authorities to collect DNA samples from anyone arrested on felony charges or arrested for a misdemeanor but that also has a felonious background. The person doesn’t have to be charged to have their DNA collected.

Authorities in California have run 192 familial searches since 2007 in 108 cases, the California Attorney General’s Office told the Bee.

"People who submit DNA for ancestors testing are unwittingly becoming genetic informants on their innocent family."

The most recent conviction using the technology came in May 2016 after “The Grim Sleeper,” Lonnie Franklin, Jr., was arrested and convicted of 10 counts of first-degree murder in Southern California for his killing spree from 1985 to 2007.

Los Angeles police also used the controversial tactic in May 2017, collecting spit from a sidewalk to tie Geovanni Borjas, 32, to the sexual assault and murder of two women who vanished in 2011.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.