Amid the mayhem and mourning that followed World War II, a striking 25-year-old legal secretary volunteered to leave the comforts of her California life to do the unthinkable: help try some of Japan’s most reviled war criminals in what became known as the “Tokyo Trials.”

Now 95, and living in Los Angeles following an illustrious legal career that only concluded recently, Elaine Fischel vividly recalls the phone call that would change her life.

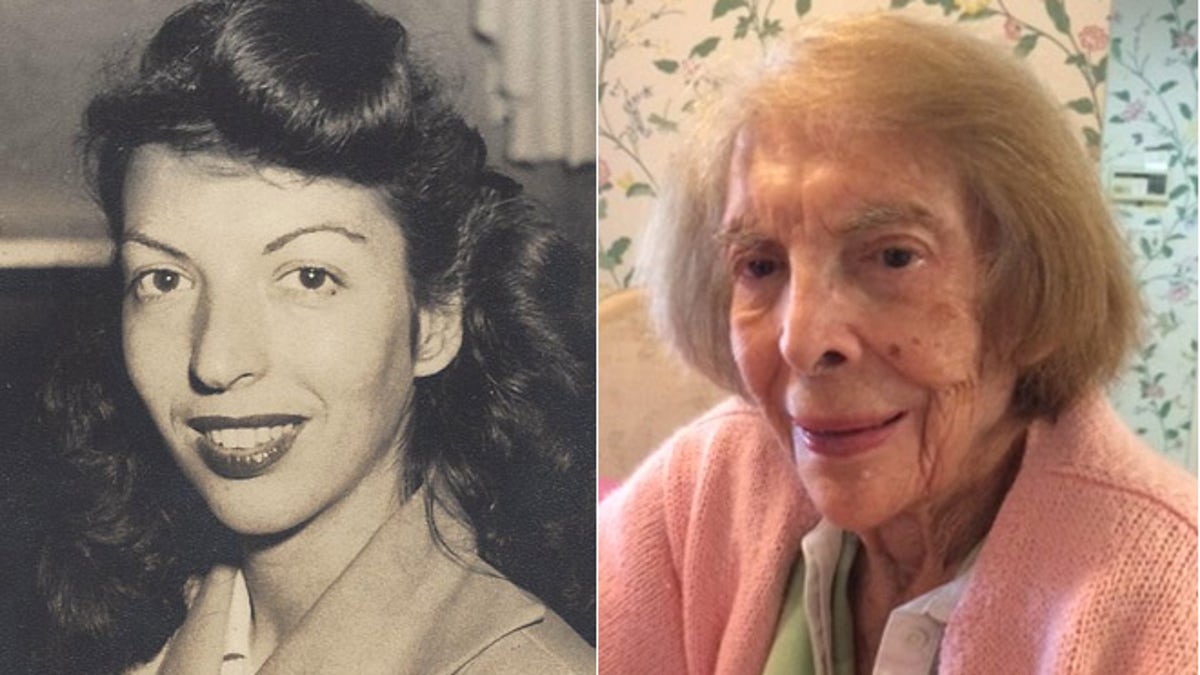

Then and now: Elaine Fischel, (l.), as a young legal secretary at the Tokyo Trials; and (r.) today in her LA home. (Courtesy: Elaine Fischel)

“I was working for the Los Angeles District Attorney as a staff secretary and I got this call from somebody I had known from when I worked in Washington, and he said, ‘You wanted to go to law school so this would be good experience,’” Fischel told FoxNews.com. “They said it would be just six months, but it turned out to go on for two-and-an-half years.”

The Tokyo Trials, officially termed the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, was convened at the former Imperial Japanese Army Headquarters building in April, 1946 – some six months after Japan surrendered –on orders of President Truman and U.S. Gen. Douglas MacArthur. Following on the heels of the Nuremberg Trials, the Tokyo procedures included judges and prosecutors from nine nations, and some 28 Japanese political and military officials charged with offenses ranging from waging aggressive war to war crimes.

“It was hard to think of them as barbarians, as they were all so polite. But there were some very, very bad men on trial.”

“The U.S. didn’t want what they called vigilante justice – a ‘We’ll take ‘em out and shoot ‘em’ approach,” said Fischel, who served as the official legal secretary. “It was agreed to give them a proper trial.

“It was hard to think of them as barbarians, as they were all so polite,” she added of the defendants. “But there were some very, very bad men on trial.”

Initially, Fischel was appointed to work with the prosecution team, but she saw a greater challenge in working for the men who had orchestrated atrocities from Pearl Harbor and the Rape of Nanking to the brutal torture and transfer of Filipino and American POWs known as the Bataan Death March and the mass murder of millions of Chinese. Ironically, it was her patriotic pride that motivated her to take on such an unpopular assignment.

“I wanted people to know that America is a great country,” she recalled. “We sent our lawyers there to defend the enemy and I don’t think any other country would do that. To me, it was an example of the United States at its best.”

Fischel became friends with the brother of Emperor Hirohito, above.

Getting to know many of Japan’s disgraced leaders and their families changed Fischel’s own perceptions of the enemy. The war had stoked her hatred for the Japanese, whose forces Fischel blamed for the deaths of many friends.

“I really thought the Japanese were horrible people,” she recalled. “The turning point was when the little 15-year-old daughter of one of the defendants came to me and asked if she could see her father. From that time onwards, I realized that these men weren’t just evil – they were fathers, husbands and sons. The lawyers viewed them as clients, not simply war criminals.”

Fischel, whose job included visiting the prisoners in their cell and taking down their requests – became a close confidante of infamous Gen. Hideki Tojo, the prime minister turned chief of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office.

The Tokyo Trials were ordered by Gen. Douglas MacArthur, (l.), and President Truman, (r.). (Associated Press)

“He always wanted to see his lawyer so he would often come up to me,” Fischel said. “I had also started horseback riding at the stable where his horses were so he always asked about that.”

Tojo believed his mission to “make Japan the leader in that part of the world” was righteous, and Japan’s role in the war was one of self-defense.

“He really thought that he had acted to protect his country,” she said.

Fischel also came to know well the military masterminds behind the Pearl Harbor attack, including Navy Capt. Yasuji Watanabe, the top aide to commander-in-chief Yamamoto Isoroku, who was shot down by U.S. Forces in 1943.

Much of Tokyo, including Nagasaki, seen here in a Sept. 13, 1945, photo, was still in ruins when Fischel arrived. (Associated Press)

Fischel recollected that the mood in Tokyo was one of devastation and defeat, yet people were working to rebuild. Women and men planted wherever there was soil, carried bricks on their shoulders for miles and ultimately became grateful for the presence of the U.S., which occupied Japan until 1952.

“They went out of their way to be nice to us,” Fischel said. “No one was ever hurt or killed in the occupation and there was no resentment.”

Fischel was invited to swanky parties with Tokyo’s elite, where strict U.S. rules forbade Americans from eating the hosts’ food to avoid the perception they were taking from the Japanese. Fischel became a close friend and tennis partner of Emperor Hirohito’s younger brother and Navy captain, Prince Takamatsu.

“I could have stayed and gotten another job but I knew it was an artificial home for an American,” she said. “We were important people, but in the real world, I was just another ordinary person who wanted to go to law school.”

The tribunal was adjourned on Nov. 12, 1948. One defendant was deemed mentally unfit for trial and charges were dropped, two died of natural causes during the process and seven were sentenced to death and executed in December, 1948, and one got a seven-year sentence. Tojo was sentenced to 20 years, but was executed in 1949. The remaining 16 were issued life imprisonment – three died while incarcerated, and the others were pardoned and released in the mid-1950s.

Avoiding the noose was considered a victory by the defendants, Fischel said. Shigetarō Shimada, chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff who was issued life but later released, even wrote a letter saying that if it wasn’t for Fischel and the legal team “he would be in heaven.”

When Fischel returned, her own nation had changed. And her own effort to launch a legal career by attending law school at University of Southern California, got off to a rocky start.

“I had been gone for several years and the war was now over, and the United States had become this consumer nation and we had all things we didn’t have before,” she said. “Many of my friends in law school were already on the G.I. Bill. I was no great scholar. I just wanted to get through.”

But six weeks in, Fischel learned she had contracted tuberculosis while in Japan. It would be more than two years before she could resume her studies. Nearly a decade later, when she returned to Japan for a visit with her mother in 1960, her old friend Prince Takamatsu expressed his pride in her budding success, as well as his own nation’s.

Japan's 1947 Constitution surrendered its sovereign right to war, and the nation has been protected by a military alliance signed with the U.S. in 1952. But in recent years, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has sought to redefine the country’s military role amid an increasingly nationalism and revision of its leadership role in the world. Last September, the government passed controversial security laws – which went into effect this week – to enable Japan to exercise conflicts in self-defense, or in aid of the U.S. and other allies.

Several years ago, Fischel penned the book, “Defending the Enemy,” about her Tokyo experience and is currently working on a second book about her long career as an attorney. She practiced law, including criminal defense and personal injury work, for 61 years, finally retiring last year, and spent many as one of only a few women in a male-dominated field.

“I always saw being a woman as an advantage, it made you stand out,” she said. “I had my own way of doing things – and I’m pretty proud of that.”