The Cedar-Riverside neighborhood is home to a large Somali community. REUTERS/Craig Lassig

MINNEAPOLIS, Minn. - In the dead of the cold, late night on Tuesday, a young Somali man was shot in the hip. Someone took him to the local trauma center, left him there, and drove off.

The man told police at his bedside that he didn’t know who shot him, who took him to the hospital, or why he was targeted. “I’m intoxicated,” he told cops, while doctors tended his wound, before insisting he didn't know anything else about what happened.

For the attending police officers, it was a frustrating, albeit familiar, response from a member of the Somali community, whose support in November sent one of their own, Rep. Ilhan Omar, to Congress. While Omar has spoken out frequently and forcefully on a range of issues - some that seem little connected to her district - most members of the Somali community she represents remain far more insular.

The national epidemic of shootings involving young African-American men in America's cities certainly isn't unique to Minneapolis. But some officers here believe issues of cultural assimilation involving the Somali immigrant community, and a struggle on both sides to better communicate law enforcement's mandate to protect and serve, makes it a particularly imposing challenge. One that politicians like Omar, they say, could do much more to effectively address.

OMAR GRILLS TRUMP ENVOY TO VENEZUELA AFTER BOTCHING HIS NAME

In this March 1, 2014 file photo, St. Paul, Minn. Community Officer Kadra Mohamed, left, smiles as she receives her badge from St. Paul, Minn. Police Chief Thomas Smith, during a ceremony for her and the East African Junior Police Academy at the Western District Police Station in St. Paul, Minn. (Sherri LaRose-Chiglo/Pioneer Press via AP)

“When they come here, they come with their own experiences of not trusting the police, and from a place where the police are known to be corrupt. And the challenge for us lies in trying to get them to cooperate,” said one law enforcement officer. “They’ll often call 911 when they need help. But when we come, they often won’t then tell us who is causing the problem so we can take action or stop the crime from happening again.”

“Our goal is to have a good relationship with the community, we try to engage but it’s proving to be a tough egg to crack,” another officer underscored.

According to data compiled last year by the Washington Post, more than half of all homicides statewide in Minnesota go unsolved. And that's in part because Somali-Americans in Minneapolis aren't talking enough to police, according to officers.

The Somali community grew here rapidly here during the 1990s, when large numbers of Somalis fled a devastating civil war. The community has since grown with the addition of U.S.-born children of those refugees - as has the debate over the Somalis' desire and ability to culturally assimilate.

Minnesota is now home to one the largest Somali communities in the global diaspora, with an estimated 100,000 living in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area. The Cedar-Riverside neighborhood is the center of the Somali community – and is fondly nicknamed “Little Mogadishu” – for its array of Somali-centered organizations, businesses, and mosques.

Last year, it was announced that massive security upgrades totaling some $825,000 were coming to the major government-funded apartment complex in Cedar-Riverside, to “address resident safety concerns.” Part of the plan was to place a six-foot perimeter fence at the Cedar High Apartments, a complex owned and managed by Minneapolis Public Housing Authority, and for many, the central meeting point for the community.

While supported by some, others expressed their concerns the fence would only further isolate the Somali population, and hinder their ability to work with them and make the area safer.

Some investigators lament the difficulties in rooting out gang violence that remains a problem in not just the Somali community, but neighboring areas. The proper dismantling of the gangs, police stress, is a two-way street. Gang activity now is no longer centered on larger outfits like MS-13, or the Crips. Much more common here are smaller gangs with names like “Somali Mafia,” “Somali Outlaws,” “Young n’ Thuggin (YNT)” and even the “Taliban.”

“It’s hard for any community to assimilate and to immediately transform from the life they knew. But the distrust is only getting worse,” said an area law enforcement official. “The gang violence is only getting worse. Not only do crimes go unsolved, but many don’t get reported at all.”

But Jeanine Brudenell, the former Minneapolis Police Department's Somali liaison officer, who retired in 2017, believes gang violence has waned somewhat. She acknowledged that while the “huge fear of police and government” has made efforts to protect the community, the right steps are being put in place in terms of community relations.

In recent years, the Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) has sought to do more community outreach, and bring into the fold more Somali officers. The department currently has eight ethnic Somalis serving as officers.

"The City of Minneapolis has the largest Somali population, per capita, in the United States. The Minneapolis Police Department strongly believes that a police department that reflects the community it serves is an important first step in building trust,” John Elder, Minneapolis Police Department Public Information Officer told Fox News. “When Somali residents see officers that look like them, on patrol and detectives in investigation units, they are more likely have the confidence the MPD will understand their culture and background.”

Elder pointed out they also have two Somali officers assigned the district with the highest concentration of Somali population, and note Chief Arradondo has placed a Community Navigator who is Somali to aid that population to work with the MPD.

But that endeavor has also come with its own set of complications.

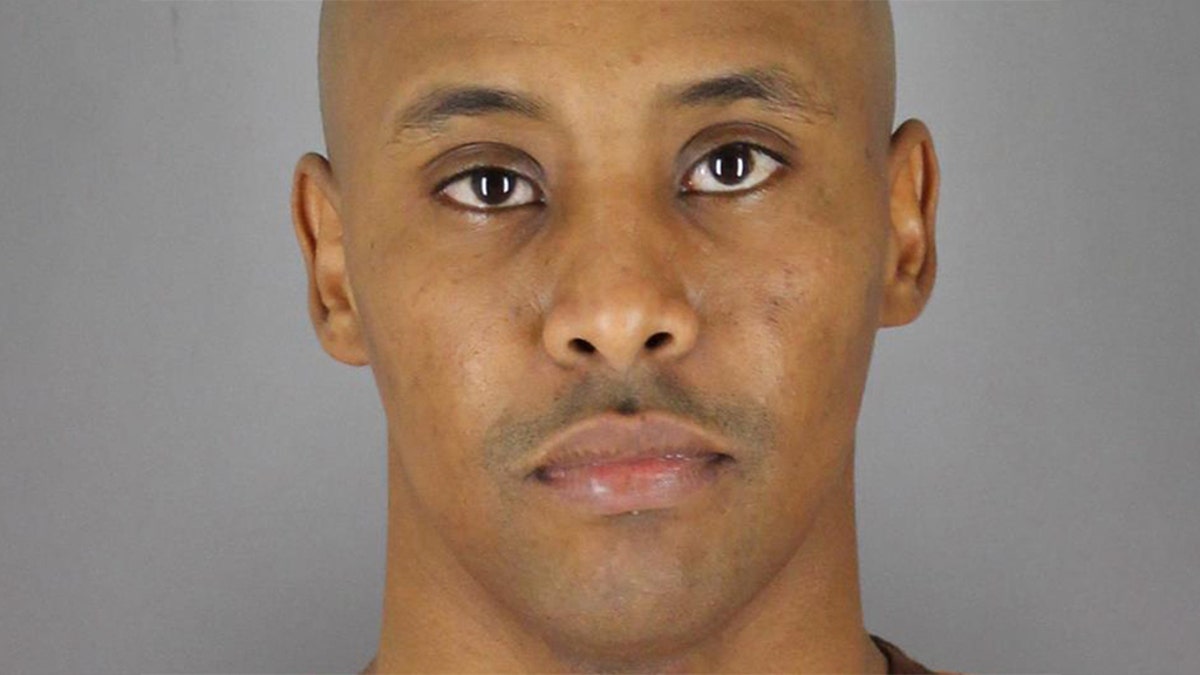

Last July, unwelcome attention came to the community after a Somali-born Minnesota police officer, Mohamed Noor - who had been lauded by Minneapolis’ mayor and championed by the local community when he joined the force in 2015 - shot and killed an unarmed Australian woman who had called to report a possible crime occurring near her house.

Mohamed Noor, 32, is pictured in this undated handout photo obtained by Reuters March 20, 2018. Hennepin County Sheriff's Office/Handout via REUTERS

The incident drew international interest. And with Noor's manslaughter trial expected to start in April - and thus re-ignite interest in the case - some expect the tension between the community and law enforcement will only tighten.

RACIST POSTS SPARK POLICE RESPONSE AT MINNESOTA HIGH SCHOOL

Omar, meanwhile, has consistently used her platform to take aim at law enforcement - including after the Noor incident.

“The idealist in me continues to be surprised, but I know this incident is another result of excessive force and violence-based training for supposed peace officers,” she said in a statement after the shooting. “The current officer training program indoctrinates individuals of all races into a system that teaches them to act first, think later, and justify with fear.”

Responding to another incident, more than a thousand miles from her district, Omar tweeted “Seriously, where are the police with full riot gear? #hypocrisy #law&order,” in response to unrest in Philadelphia that broke out after the Eagles won the Super Bowl in February, 2018.

Rep. Ilhan Omar, D-Minn., arrives for President Donald Trump's State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress on Capitol Hill in Washington, Tuesday, Feb. 5, 2019. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

For some officers, that kind of pushback from the top does more to divide than unite. And for the locals on the ground, that divide is deeply felt.

Local Somalis were generally reluctant to speak with Fox News this week on the subject of community-police relations. Similarly, Jaylani Hussein, a Somali-American who serves as the executive director of the Minnesota chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), did not respond to a request for comment. Attempts to reach out to several other Somali-American groups went unanswered.

But one local man, Said, who came to the U.S. as a refugee in 1992, and said he raised his children alone as a single father in the community, said the perception of many is that racism against the Somali community is endemic.

“They might pull you over and give you a ticket for a reason you don’t know. And if you try to argue, they just tell you to go to the court and deal with it,” Said observed, arguing that while police and the government in Somali are outwardly corrupt – Transparency International ranks it the most corrupt country on the planet – in the U.S., some Somalis believe the corruption is more hidden.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

For others, however, there's simply the strong desire to stay clear of law enforcement - in any capacity.

“We don’t want any problems. We don’t want to have to deal with police,” said Sadi, a local store owner, and a mother. “Many people have come from war, and we just want peace.”