A mother who lost her daughter to fentanyl poisoning is pushing to criminalize drug deaths

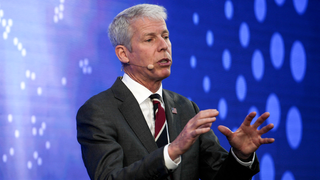

Former Chicago police officer Terry Almanza joined 'Fox & Friends First' to discuss her fight for justice as overdose deaths climb nationwide.

Early on the morning of Sept. 29, 1982, a 12-year-old girl, Mary Kellerman, came down with a sore throat and a runny nose, and her parents gave her one extra-strength Tylenol. Hours later, she was dead.

Over the next several days, six more people in the Chicago area died suddenly after taking the then-best-selling non-prescription pain reliever.

Investigators soon realized that each victim had swallowed a tablet laced with a lethal dose of cyanide. The pill manufacturer, Johnson & Johnson, determined that the bottles had been tampered with after leaving the factory.

Someone had taken the bottles off the shelves at several drug stores, added poison to the capsules and then put them back, with unwitting customers purchasing the deadly concoctions.

Drugstore clerk removes Tylenol capsules from the shelves of a pharmacy September 30, 1982, in New York City after reports of tampering. Seven people died in Chicago after taking Tylenol. (Yvonne Hemsey/Getty Images)

Thursday marked the 40th anniversary of Kellerman's death and the still-unsolved murders that panicked the country and transformed the way over-the-counter medications are packaged.

A Massachusetts man, James Lewis, claimed he was the Tylenol killer in a 1982 ransom letter to Johnson & Johnson, demanding $1 million in exchange for stopping the drug store contamination.

CHICAGO TYLENOL MURDERS REMAIN UNSOLVED AFTER MORE THAN 30 YEARS

But authorities determined that Lewis wasn't in the Chicago area at the time. He was convicted of extortion and served 13 years in prison. Some investigators still believe Lewis was behind the murders, which he has repeatedly denied.

A new report from the Chicago Tribune says that three Chicago police detectives still believe that an old suspect, amateur chemist Roger Arnold, is the Tylenol killer.

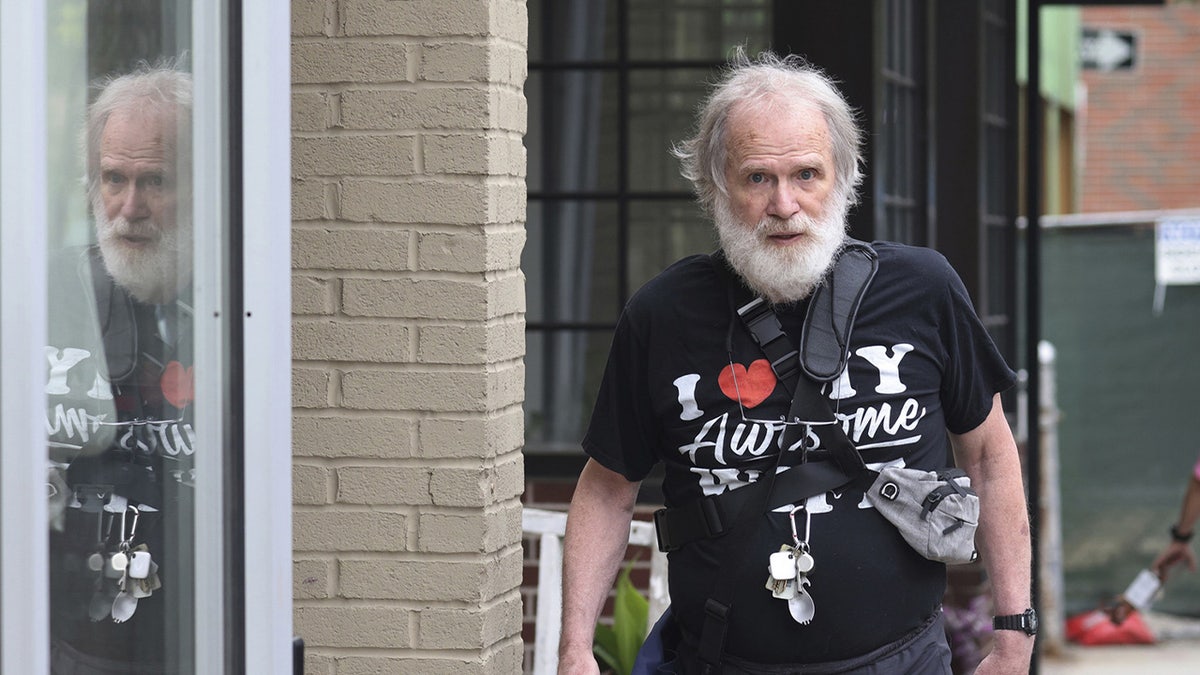

James Lewis, 76, walks in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Some investigators have renewed their efforts to pin the Tylenol murders on Lewis, who was convicted of sending an extortion letter to manufacturer Johnson & Johnson but has repeatedly denied being the Tylenol killer. (Stacey Wescott/Chicago Tribune/Tribune News Service via Getty Images)

A bar owner, Marty Sinclair, tipped off authorities after the cyanide death, saying that Arnold had become erratic after his marriage had crumbled and that he had been known to keep the poison in his home.

"He just struck me as being real resentful of his lot in life," said retired Chicago Detective Jimmy Gildea, who interviewed Arnold at the time. " I think he was kind of a broken little man, really."

Authorities amassed a mountain of circumstantial evidence – including Arnold's admissions that he wanted to poison people and connections to the drug stores that sold the tainted pills. But there wasn't enough for an arrest.

The FBI wasn't on board, according to the newspaper, and when the ransom later came in, the agency switched gears and focused on Lewis.

A foil safety seal that became standard on all over-the-counter medications after the 1982 Tylenol murders.

After the spotlight dimmed on Arnold, he shifted his attention to revenge. He learned from a police report that Sinclair had ratted him out for having cyanide.

One night, he spotted a man he believed was his nemesis outside a local watering hole and shot him in the heart -- but it was a case of mistaken identity.

He killed a stranger who happened to look like Sinclair. At trial, he was convicted of murder and served 15 years in prison. Nearly a decade after his release, he died of natural causes in 2008.

The murders spurred medication manufactures to introduce tamper-resistant bottles with foil seals and other features that make it easy for consumers to tell whether a container has been altered.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

In 1989, the FDA created federal guidelines that forced all manufactures to make over-the-counter medications tamper-resistant.