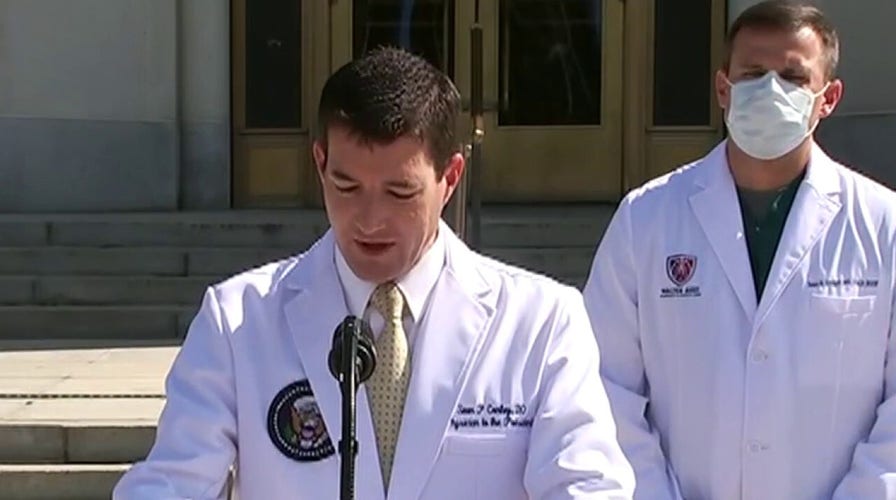

In the critical days since President Trump announced that he and the first lady had been infected with the novel coronavirus, the eyes of the world have been fixed on one place: a sprawling parcel of manicured green lawns and matchbox-like ivory dwellings known as the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC).

It was announced on Friday evening that "as a precautionary measure" Trump would be transferred to the facility, also known as the President's Hospital and the Nation's Medical Center. Throughout the tense weekend, the president extolled the virtues of the hospital staff, illuminating the "incredible institution."

Named after Maj. Walter Reed, an Army researcher who helped prove that an earlier viral epidemic, yellow fever, was transmitted by mosquitoes – it comes with a storied history. President Ronald Regan stayed at the former Walter Reed when he had his surgery in 1989, PresidentRichard Nixon battled pneumonia in his isolated chambers there in 1973, and the slain body of President John F. Kennedy was transported from Dallas to the hospital on that frosty November day in 1963.

TRUMP THANKS SUPPORTERS GATHERED OUTSIDE HOSPITAL: 'I'M ABOUT TO MAKE A LITTLE SURPRISE VISIT'

The hospital is also the go-to for the vice president, members of Congress and Supreme Court justices. But its legacy is most often entwined with treating members of the U.S. military and their families. So for those who have spent significant chunks of their lives at the eponymous, now state-of-the-art Walter Reed, it's a name that conjures up many memories – a place of both healing and pain, a place that signifies the many wounds of war, visible and invisible.

"Back then, we went from five to 10 severely wounded and amputated to nearly 50 in a matter of just a few months," said Johnny "Joey" Jones, a former U.S. Marine and Fox News contributor who lost his legs to an IED while in Afghanistan in summer 2010. "But no one can care for a Marine like a hospital corpsman. The staff there is truly a godsend to those in their wards."

President Trump photographed working from a conference room at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center on Saturday, Oct. 3, 2020, after testing positive for the coronavirus.

The facility as it stands now is the combination of the Walter Reed Army Medical Center -- which opened in 1906 -- and Bethesda's National Naval Medical Center. They were merged in 2011 at the direction of Congress to form the WRNMMC, quite simply tagged "the new Walter Reed" by many others who have been forced to take up residence inside the heavily sterilized walls.

Retired Lt. Colonel Rudolph Atallah, who served as the Africa counterterrorism director and Morocco/Tunisia country director in the office of the Secretary of Defense, said the Walter Reed was his personal stomping grounds for more than a decade and also tendered with great care and pragmatism to his ex-wife, who was diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma cancer.

"It is a special place. Being a military hospital, the staff are always kind -- but they are all in uniform, so to speak, and we are all still treated like soldiers," Atallah noted.

Atallah also praised the relationships that the hospital had established with other experts, including the best of the best at Harvard and Johns Hopkins universities.

Flowers and balloons left by supporters of President Donald Trump at the entrance to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (background) in Bethesda, Md., Sunday, Oct. 4, 2020. Trump was admitted to the hospital after contracting the coronavirus. (AP Photo/Cliff Owen)

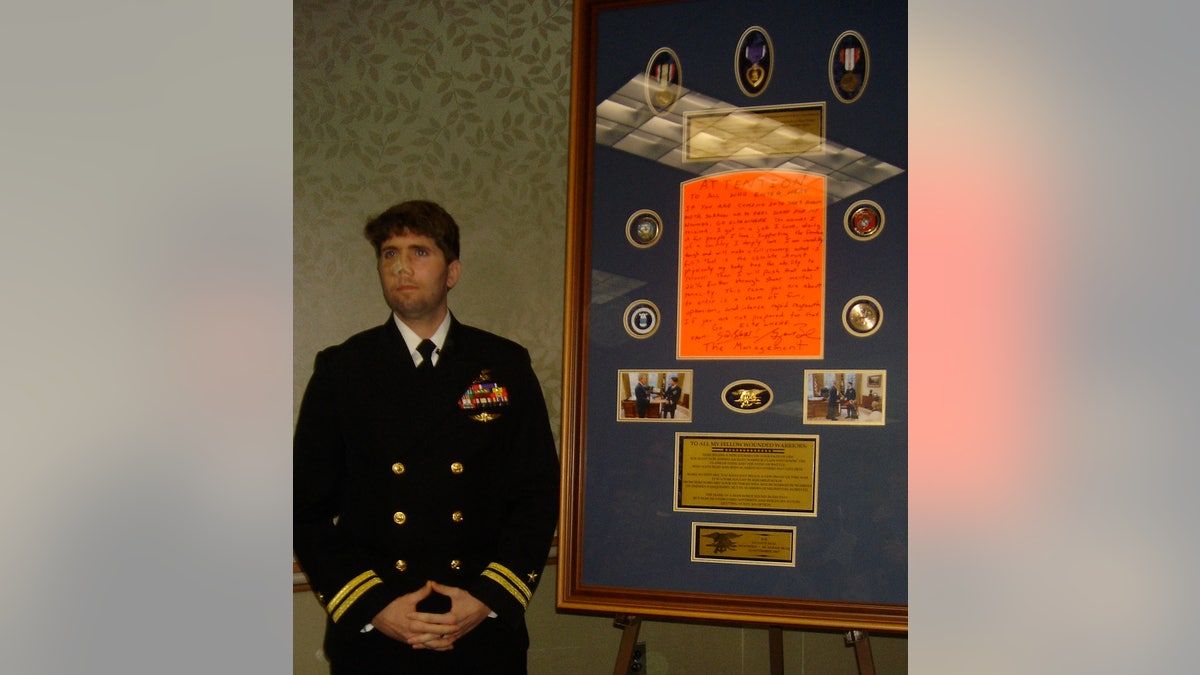

For former Navy SEAL Jason Redman, whose face and body was blown up in Fallujah in September 2007 – signaling some eight weeks of treatment at the Bethesda Naval hospital campus in addition to countless visits over the ensuing years – it was those external relationships that played a pivotal role in saving his life.

"They had me to see one of the best facial reconstruction surgeons in the world, from Johns Hopkins, their egos never got in the way," he said. "If there was another doctor they believed could do a better job, they went and found them. Patient and mission were more important to them than their own egos."

THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT WALTER REED NATIONAL MILITARY MEDICAL CENTER – 'THE PRESIDENT'S HOSPITAL'

Former Navy SEAL Jason Redman, whose face and body were blown up in Fallujah in September 2007, signaling some eight weeks of treatment at the Bethesda Naval hospital campus. In addition to countless visits over the ensuing years, it was those external relationships that played a pivotal role in saving his life. (Courtesy Jason Redman)

Redman also spoke to the sense of stability that stemmed from being in a military hospital. He recalled firing the civilian nurses contracted by the DoD at the time, insisting he only is cared for by U.S. servicemen and women.

"The military nurses were consistently, always, incredible," Redman said. "Sometimes in the hospital system, a patient just becomes a number on a chart -- but the military staff never forgot we were human beings, they appreciated I was more than a slab of meat."

At one point, he recollected, he awoke from one of the countless surgeries and, still swirling with anesthesia, started reliving the firefight from the roofs of a bombed Fallujah. And when efforts to hold him down were failing, staff had the wherewithal to break standard protocol and bring his beloved wife, Erica, into the room to instill calm.

Yet for Jennifer Horn (nee Lee), the onslaught of Walter Reed reminders over the past few days has brought one potent memory to the surface: Even when wounded, the patients were still summoned "to get up and do formations," ensuring their military discipline did not fall to the wayside.

Horn was just 22 when shrapnel entered her right eye, sliced through her foot, and seared the left side of her body during a mortar attack in Mosul, Iraq, in 2005. Now a registered nurse herself, Horn not only touts the level of care but also the internal mending that comes from having others around her who just "get it."

Jennifer Horn was just 22 when shrapnel entered her right eye, sliced through her foot, and seared the left side of her body during a mortar attack in Mosul, Iraq, in 2005. (Courtesy Jennifer Horn)

She and the growing files of others all shared a tragic bond.

"At first, in my stay, I was pretty out of it," Horn surmised. "Then I started to get to really know the others healing around me, one I am still in touch with today."

And for other veterans, such as U.S. Army veteran Boone Cutler, the hospital conjures up much darker memories.

"There were too many there who were sick and injured; there wasn't enough care. But they (the staff) were just as overwhelmed as everyone else," recalled Cutler, a retired U.S. soldier who suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) in Baghdad's Sadr City in 2005 and went on to develop immediate PTSD symptoms. "What happened with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, is that -- due to advances in technology -- people were surviving things that in wars of the past, they wouldn't have survived."

For U.S. Army veteran Boone Cutler, the name Walter Reed hospital conjures up dark memories. (Courtesy Boone Cutler)

In the early days of 2007, shocking anecdotes poured through the press in what quickly became the "Walter Reed neglect scandal," shedding light not only on the squalid living conditions many wounded warriors were compelled to endure but also the lack of adequate treatment in what was supposed to be the world's premier military medical facility.

PRESIDENT TRUMP RELEASES UPDATE, SAYS HE'S FEELING 'MUCH BETTER' AFTER HOSPITALIZATION

The revelations ignited a fervent national debate over the severity of injuries flooding in from the battleground, bureaucratic indifference and ultimately prompted several congressional and executive actions, and several high-ranking officers involved in Walter Reed's management were compelled to step down.

Cutler went on to spend two years at the old Walter Reed – a center he remembers chillingly as a "chemical prison."

"We were given drugs as a panacea to hold us over, and because of the meds, I isolated. I did not want to be close to anybody. I would like to say that spending so much time there was uncommon, but at that time, it was not," Cutler asserted. "There were always influxes of new faces, on top of faces that had been there for months going into years. I can only hope now – for our president and our troops – that is has gotten a lot better now."

It is now the largest joint military medical center, with more than 2.4 million square feet of clinical space set on 244 acres in Bethesda, Md, – some 9 miles from D.C. According to DoD statistics, more than a hundred recipients are treated at Walter Reed each year; it holds 244 beds and has a staff roster of around 7,100.

As the nation's Commander-in-chief, Trump has been delegated to the VIP treatment ward, otherwise called Ward 71.

While the medical center itself is run by the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), the imposing, six-room presidential suite is entirely controlled by the White House and peppered with protective devices and communications systems. It features everything from an intensive care unit, upscale dining room and kitchen to a living room, secure conference areas and offices, as well as sleeping quarters for the White House physician and other key staffers to remain present around-the-clock.

Moreover, Matt Creamer, who resided at Walter Reed from May 2011 to April 2013 and was shuffled from the old grounds to the new, said the relocation and upheaval was one of the best moves that the government could have made.

"I do remember having the feeling that Walter Reed was a dark place that felt dirty. Almost like the pressure of the building was weighing in on you," he conjectured. "Once the move was made to Bethesda (the new Walter Reed), it felt fresh. It was as if you could breathe."

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Yet one token of the past still remains.

While Redman was recovering, he hung up a sign on his hospital door – a vivid tangerine sign still standing in the bright lights of the medical center today.

Jason Redman, a former Navy SEAL, stands beside the sign he once placed on his door at Walter Reed. (Courtesy Jason Redman)

"Attention to all who enter here. If you are coming into this room with sorrow or to feel sorry for my wounds, go elsewhere. The wounds I received I got in a job I love, doing it for people I love, supporting the freedom of a country I deeply love," it reads. "This room you are about to enter is a room of fun, optimism, and intense rapid regrowth. If you are not prepared for that, go elsewhere."