Jailed Iranian musician Mehdi Rajabian refuses to stop playing. (Mehdi Rajabian)

Mehdi Rajabian, 29, is on temporary bail from the brutality that lurks behind the walls of Tehran’s notorious Evin prison – but he wants the world to know the oppression and fear he and many more face at every moment under the iron thumb of the regime.

His crime? A childhood love of music.

“I was born in a small province in Iran. I was always passionate about music, I would drown in the imagination of color and fairytale while listening to music,” Rajabian told Fox News from Iran, which he is forbidden to leave. “This childish, visual view of music made me see it as a means to carry an artistic message.”

But that view would one day see him thrown behind bars in one of the world’s worst prisons.

Iran's notoriously brutal Evin Prison in northern Tehran (Behrouz Javid Tehrani/IHRDC)

REPORTER JASON REZAIAN REVEALS 'TORTURE' HE ENDURED IN IRANIAN PRISON

His trouble began in 2013 after he and his older brother, Hossein, were investigated and detained by authorities for “spreading corruption” after their participation in Iran’s fabled underground music scene, and working with women.

“Women in Iran can’t perform as solo vocalists, it is forbidden. And it is forbidden to show musical instruments on national television,” Rajabian pointed out. “We are creating music in such hardships, where music can be counted as a felony. One must learn and play music in such situations.”

Then, in June 2015, Rajabian and Hossein, a then 31-year-old filmmaker, were again arrested found guilty of “spreading propaganda against the system” and “insulting the sacred.” He was cautioned never again to participate in the music industry.

After months of solitary confinement, then being moved around to cells with an array of Somali pirates and drug dealers, the brothers embarked on lengthy hunger strikes to challenge their situation.

“Solitary confinement kills one's soul, and the hunger strike kills one's body, which I experienced both. I went on two separate hunger strikes, the last one lasted for more than a month where I lost 33 pounds, and my body suffered damage of which I'm still trying to cure,” Rajabian recalled. “The damage was more mental. The only thing that motivated me to keep fighting was the fight for music and for the chance to keep creating art.”

Rajabian’s plight captured the attention of numerous human rights and advocacy groups around the world, from Amnesty International and the United Nations to Free Muse, the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran and the Council of Europe Artists, all calling for his release.

EXPERTS WARN OF IRANIAN 'CYBER WAR' MEDDLING AHEAD OF ISRAELI ELECTION

While the brothers were initially sentenced to six years in jail, an appeals court commuted it to three. In late 2017, they were let out on a temporary release and remain on a suspended sentence with no end date.

“That means they (the authorities) can operate it whenever they want, which means I am still under pressure,” Rajabian said. “Hearings for people like us are held very secretly, they are highly unpredictable, they can send me to prison whenever they want.”

Despite the persistent threat of a door being knocked down, followed by a drag back behind bars – not being allowed to leave the country and banned from working as an artist – Rajabian remains defiant.

“I’m not worried about the future, because I chose my path years ago,” he stressed. “I’m always fighting for music, and music freedom.”

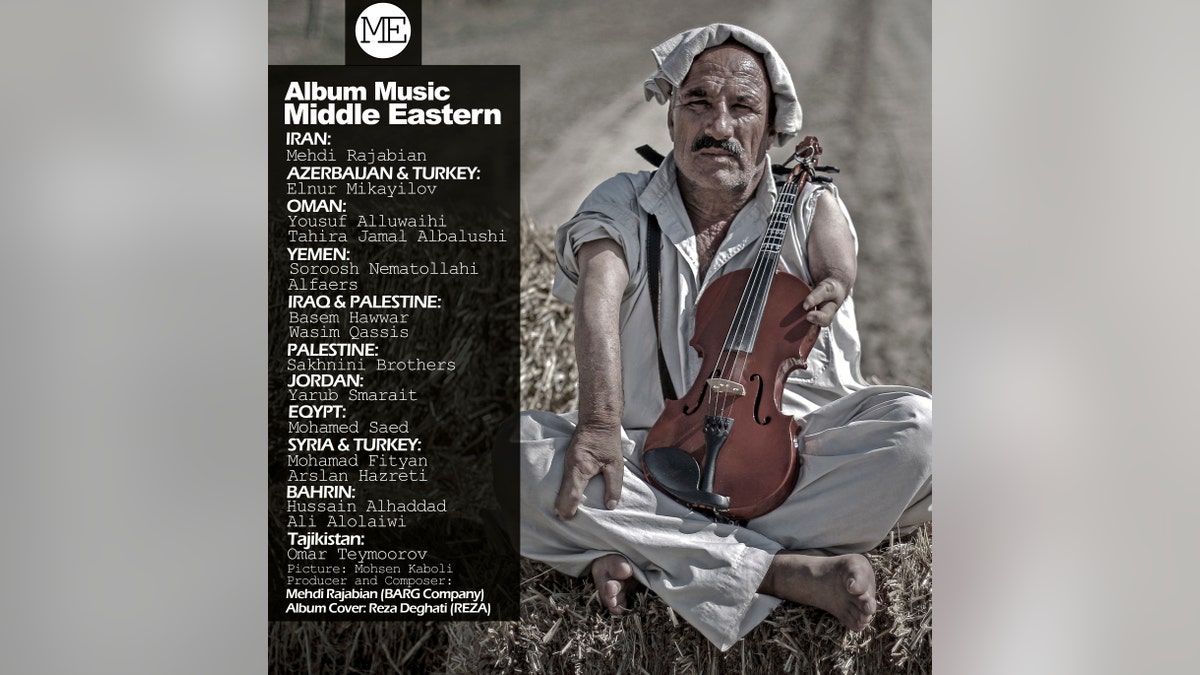

Album cover (Mehdi Rajabian)

This year, Rajabian brought together almost a hundred musicians from across the Middle East to send a message to the volatile region that they’re tired of being censored and oppressed, that they’re tired of mass human rights violations and endless wars.

Simply titled “Middle Eastern,” the eleven-track album – released last month by Sony Music Entertainment – features artists who have never met another but carry the same directive spanning Syria, Iran, Yemen, Lebanon and beyond. One created his music while bombings were exploding, another worked while on a boat fleeing his country.

“We express our pain through music. Our art is no way just for fun,” Rajabian added. “In Iran, creating art can have very harsh consequences.”