Science pioneer Margaret Hamilton wrote the moon-landing software — a giant leap for womankind. Here's her amazing story.

Computer prodigy Hamilton was just 32 years old when Apollo 11 put men on the moon, guided by her innovative software that saved the mission from being aborted minutes before landing on the lunar surface.

The Apollo 11 moon landing was one giant leap for womankind.

Credit Margaret Hamilton, a 32-year-old mother and computer whiz at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who wrote the software that placed Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon on July 20, 1969.

She also worked on the five moon-landing missions that followed.

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO CREATED AIR JORDAN SNEAKERS: PETER MOORE, LEGEND OF GLOBAL DESIGN

The director of software engineering at MIT's Instrumentation Laboratory, Hamilton was a pioneer of computer science in a transformative era, and on a transformative mission, in human history.

"The moon landing should be remembered for the spirit of possibility that turned science fiction into reality," NASA chief historian Brian Odom told Fox News Digital.

Margaret Hamilton, circa 1969, demonstrating the inside of the Apollo 11 capsule. Hamilton led the team that wrote the command module and lunar module software for the Apollo program. (Science History Images/Alamy Stock Photo)

"Margaret Hamilton," he added, "was instrumental to that success."

Working in fields dominated by men, Hamilton often had her toddler at her side as she wrote the code that changed humanity's relationship with the heavens forever.

"There was no second chance. We took our work seriously, many of us beginning this journey while still in our 20s." — Margaret Hamilton

She pioneered asynchronous software, or the ability of a program to handle multiple functions at the same time.

Her foresight saved the Apollo 11 mission from potential disaster minutes before the lunar module Eagle touched down on the moon.

She is also credited with coining the phrase "software engineer," a job title now ubiquitous in business culture.

The three crew members of NASA's Apollo 11 lunar landing mission pose for a group portrait a few weeks before the launch, May 1969. From left to right, Commander Neil Armstrong, Command Module Pilot Michael Collins and Lunar Module Pilot Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin Jr. (Space Frontiers/Getty Images)

Yet Hamilton lived in the shadows of NASA lore for decades — her name and incredible role in one of humanity's greatest achievements known only to friends and Apollo program insiders.

It took NASA itself more than 30 years to honor the women whose programming ingenuity put men on the moon.

SOLAR ECLIPSE 2024: WHERE AND HOW TO VIEW THE RARE ORBIT HITTING THE US

"I was surprised to discover she was never formally recognized for her groundbreaking work," Dr. Paul Curto, senior technologist for NASA's Inventions and Contributions Board, said in 2003 when Hamilton was finally honored with a NASA Exceptional Space Act Award.

"Her concepts of asynchronous software, priority scheduling, end-to-end testing and man-in-the-loop decision capability, such as priority displays, became the foundation for ultra-reliable software design."

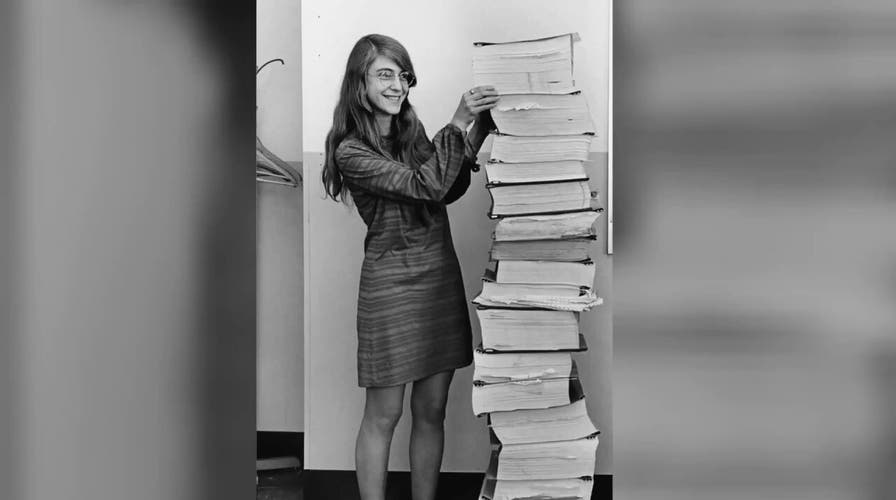

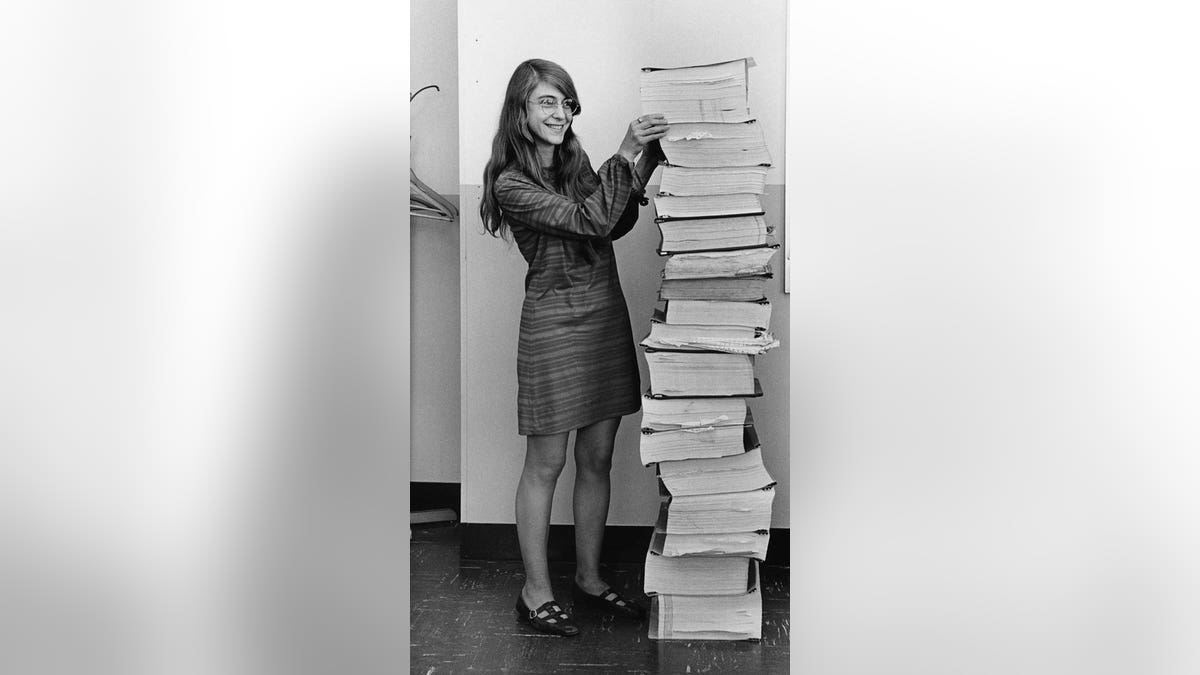

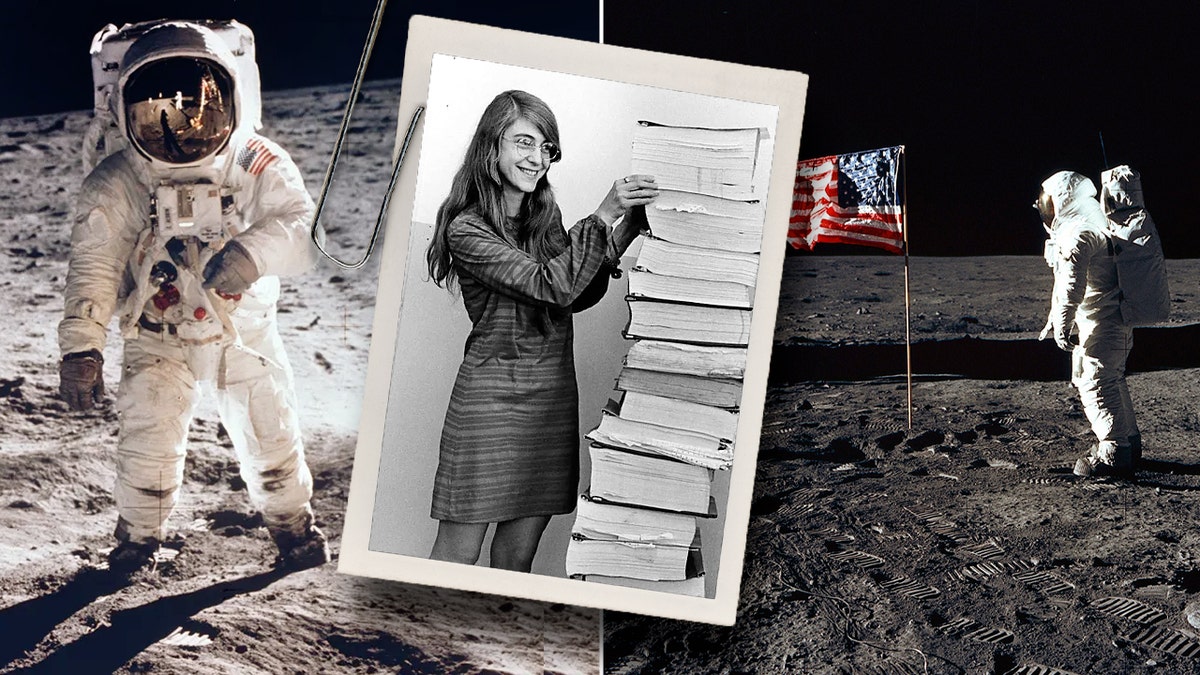

Margaret Hamilton in 1969, showing the programming code that she and her colleagues wrote to power the Apollo 11 moon landing. (Public Domain sourced/access rights from Archive PL/Alamy Stock Photo)

Hamilton's star began to rise, finally, over American science in recent years, when an incredible photo emerged on social media showing the smiling young woman beside a stack of papers that reached the top of her head.

The image of Hamilton with her remarkable pile of programming was captured at MIT Instrumentation Laboratory, now known as Draper Labs, in 1969.

"The moon landing should be remembered for the spirit of possibility that turned science fiction into reality." — NASA historian Brian Odom

It represented the giant intellect of a small-town Midwestern woman who helped secure one of the great achievements in human history.

"There was no second chance," Hamilton told MIT News in 2009 of the Apollo 11 moon mission.

Buzz Aldrin's footprint on the Moon, Apollo 11 mission, July 1969. The Apollo 11 Lunar Module, code named Eagle, with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on board, landed in the Sea of Tranquility on July 20, 1969. (Heritage Space/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

"We knew that. We took our work seriously, many of us beginning this journey while still in our 20s."

Small-town girl with big dreams

Margaret Elaine (Heafield) Hamilton was born on Aug. 17, 1936 in Paoli, Indiana, to Kenneth Heafield and Ruth Esther (Partington) Heafield.

Her father wrote poetry and encouraged her artistic side, which complemented her obvious mathematic and technical skills.

Margaret H. Hamilton, after receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom in the East Room of the White House on Nov. 22, 2016. The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest honor for civilians in the United States of America. (Cheriss May/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

The family moved to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, where Hamilton graduated from rural Hancock High School in 1954.

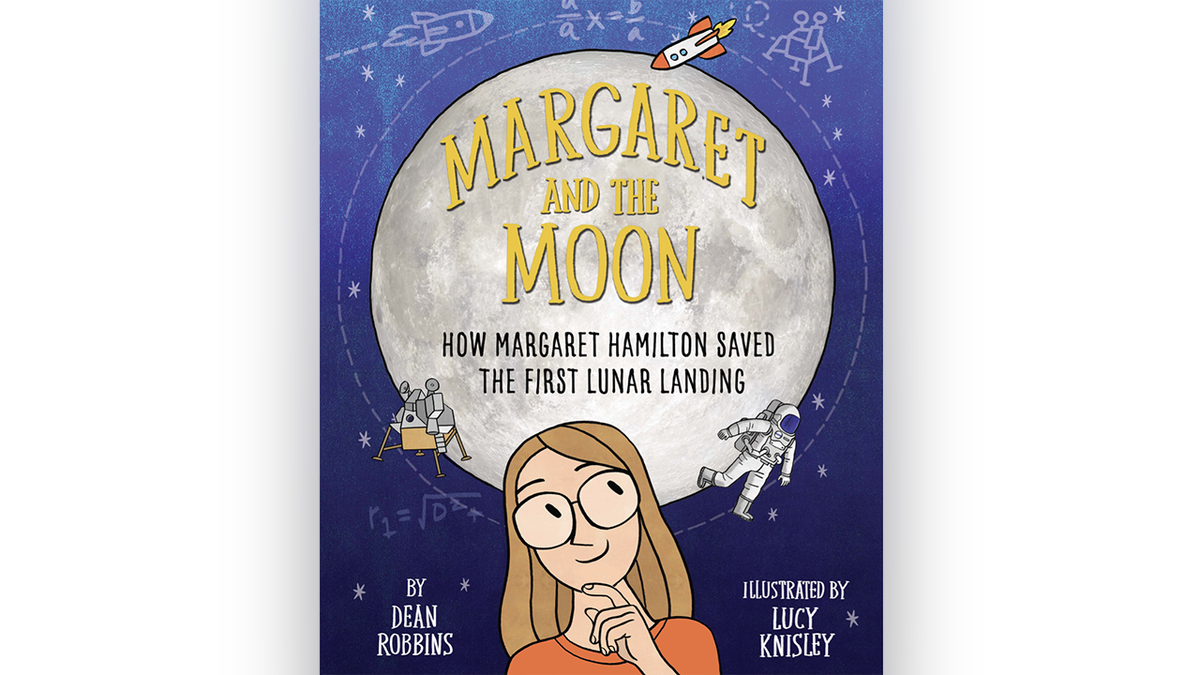

"She was obviously somebody interested in breaking through barriers, even as a child," author Dean Robbins told Fox News Digital.

"She wondered why insects were called daddy long legs, so she started calling them mommy long legs. She joined the boys' baseball team to prove she could do it."

Robbins is among the many people inspired in recent years by the image of the smiling all-American girl standing next to the giant stack of computer programming.

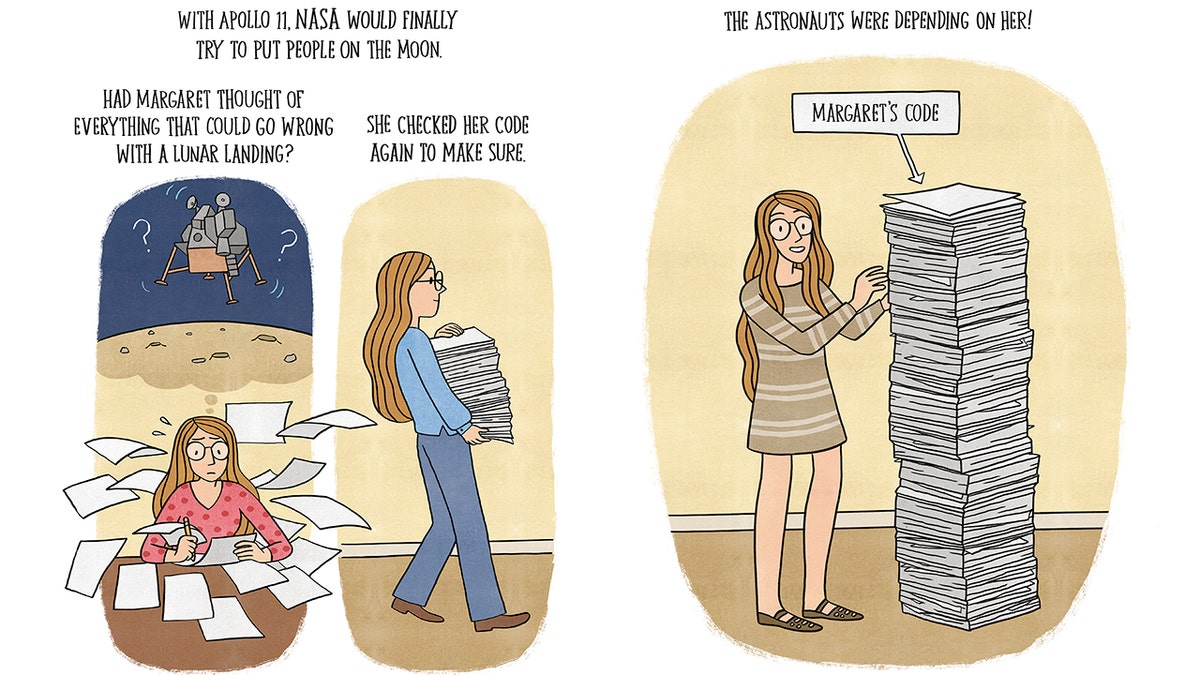

"Margaret and the Moon" (2017) written by Dean Robbins and illustrated by Lucy Knisley, tells young readers the story of pioneering computer scientist Margaret Hamilton, who wrote the software for the Apollo 11 moon landing. (Penguin Random House)

He wrote the children's book "Margaret and the Moon" in 2017, sharing Hamilton's story with young readers, aided by whimsical illustrations from Lucy Knisley.

Hamilton entered college at the University of Michigan, before transferring to tiny Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana, where she studied mathematics and philosophy.

"I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon." — President Kennedy, 1961

She began working for MIT in 1959, first under the tutelage of pioneering computer scientist and meteorologist Edward Norton Lorenz.

By 1961, she was helping MIT develop defense systems for the U.S. military, while working to put her then-husband, James Cox Hamilton, through law school.

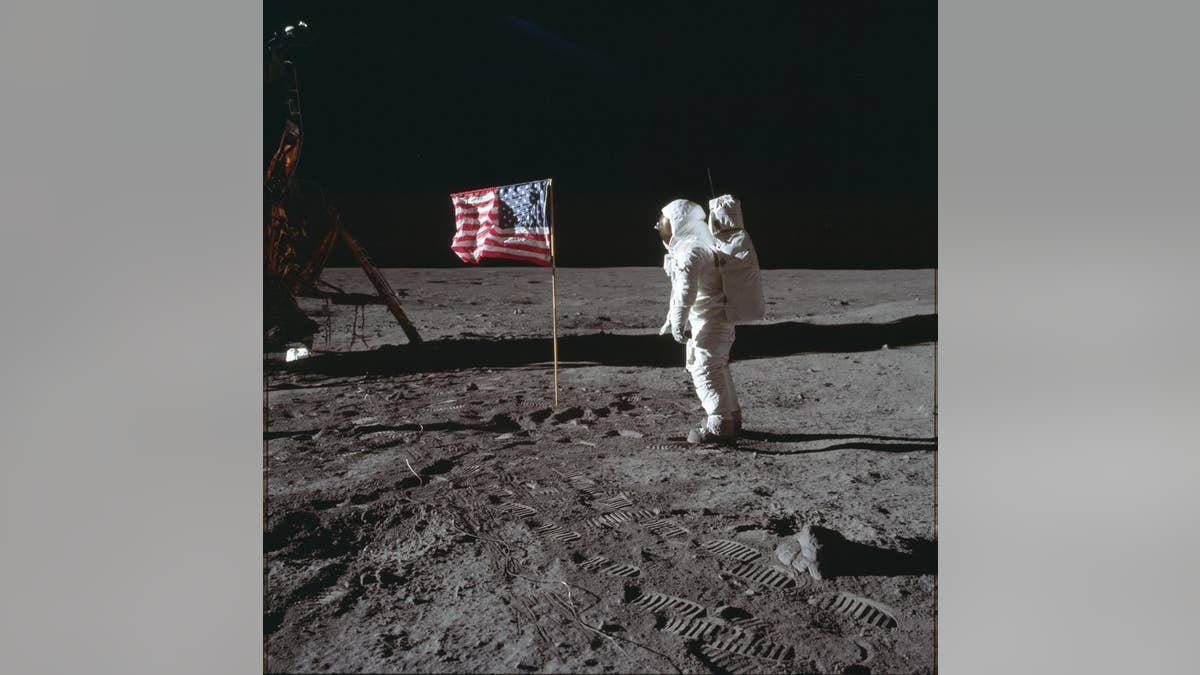

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin Jr. walking on the moon during the Apollo 11 mission, July 20, 1969. (NASA/Getty Images)

Hamilton's trajectory — humanity's trajectory — began to change when President John F. Kennedy issued an audacious call to the nation in a speech before a joint session of Congress on May 26, 1961.

"I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth," the president said in his dramatic challenge.

"As a working mother in the 1960s, Hamilton was unusual; but as a spaceship programmer, Hamilton was positively radical." — Wired magazine

"In order to accomplish the mission, somebody had to invent the modern concept of software," said Odom.

That somebody was Hamilton.

She was put in charge of MIT Instrumentation Laboratory's software engineering division in 1965.

Young Margaret Hamilton dreams of the heavens. "Margaret and the Moon" (2017), written by Dean Robbins and illustrated by Lucy Knisley, tells young readers the story of pioneering computer scientist Margaret Hamilton, who wrote the software for the Apollo 11 moon landing. (Penguin Random House)

"As a working mother in the 1960s, Hamilton was unusual; but as a spaceship programmer, Hamilton was positively radical," Wired magazine wrote in 2015.

"Hamilton would bring her daughter Lauren by the lab on weekends and evenings. While 4-year-old Lauren slept on the floor of the office overlooking the Charles River, her mother programmed away, creating routines that would ultimately be added to the Apollo’s command module computer."

‘Something totally unexpected’

Hamilton — along with her pioneering asynchronous software for the first moon mission itself — faced a moment of truth on July 20, 1969.

"I had lived through several missions before Apollo 11 and each was exciting in its own right, but this mission was special," Hamilton told MIT News in 2009.

In this July 20, 1969, photo made available by NASA, astronaut Buzz Aldrin Jr. poses for a photo beside the U.S. flag on the moon during the Apollo 11 mission. (Neil Armstrong/NASA via AP, File)

"We had never landed on the moon before. The media, most notably Walter Cronkite, was reporting everything in great detail. Once it was time for liftoff, I focused on the software and how it was performing throughout each and every part of the mission."

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO REPORTED THE FIRST SENSATIONAL UFO ENCOUNTERS, PURITAN LEADER JOHN WINTHROP

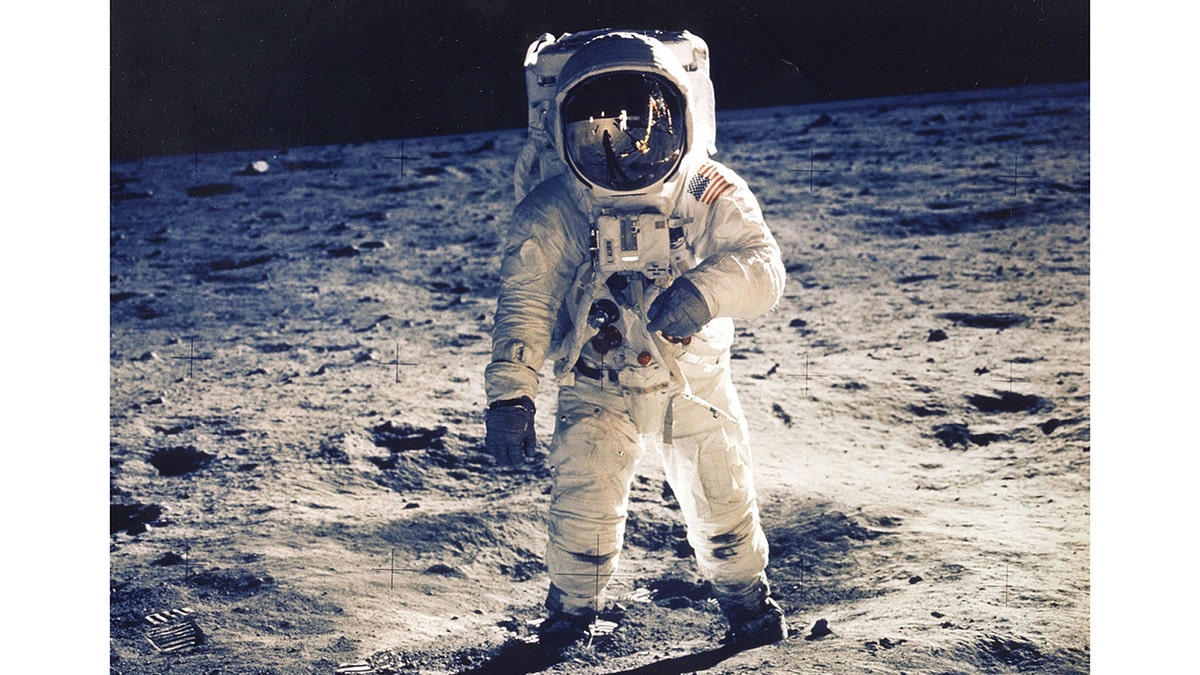

The Apollo 11 lunar module, the Eagle, was just three minutes away from landing on the moon when disaster threatened to strike.

"Everything was going according to plan until something totally unexpected happened, just as the astronauts were in the process of landing on the moon," Hamilton said in that same interview.

Alarms and error messages shocked the astronauts and mission controllers.

The astronauts had a faulty checklist, one that incorrectly told them to hit the rendezvous radar hardware switch.

Actor and filmmaker Tom Hanks (center), along with NASA mathematician and computer software pioneer Margaret Hamilton (second from right) leave an East Room ceremony in which they were awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom at the White House on Nov. 22, 2016. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Aldrin, following the checklist, hit the wrong button, Odom said, one that told the onboard computer to rendezvous with the command module rather than continue on its flight to the moon.

Mission Control was faced with the possibility of aborting the mission — or, worse, losing Aldrin and Armstrong.

AMERICAN SPACE LEGEND BUZZ ALDRIN MARRIES 63-YEAR-OLD GIRLFRIEND ON HIS 93RD BIRTHDAY

Yet Hamilton had built the software, primitive by today's standards, to compensate for just such a scenario.

"For a moment Mission Control faced a ‘go/no-go’ decision, but with high confidence in the software developed by computer scientist Margaret Hamilton and her team, they told the astronauts to proceed," Smithsonian Magazine wrote of the frightening moments before the moon landing.

Margaret Hamilton with moon-landing programming documents. "Margaret and the Moon" (2017) written by Dean Robbins and illustrated by Lucy Knisley, tells the story of pioneering computer scientist Margaret Hamilton. (Penguin Random House)

"The software, which allowed the computer to recognize error messages and ignore low-priority tasks, continued to guide astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin over the crater-pocked, dusty crust of the moon to their landing."

Said Hamilton of the anxious moments, "It quickly became clear that the software was not only informing everyone that there was a hardware-related problem, but that the software was compensating for it," she told MIT News.

With only minutes to spare, the decision was made to go for the landing.

"Fortunately, the people at Mission Control trusted our software," she said.

Hamilton's software had saved the moon mission. The Eagle landed with just 30 seconds of flight fuel left.

‘We had to find a way and we did’

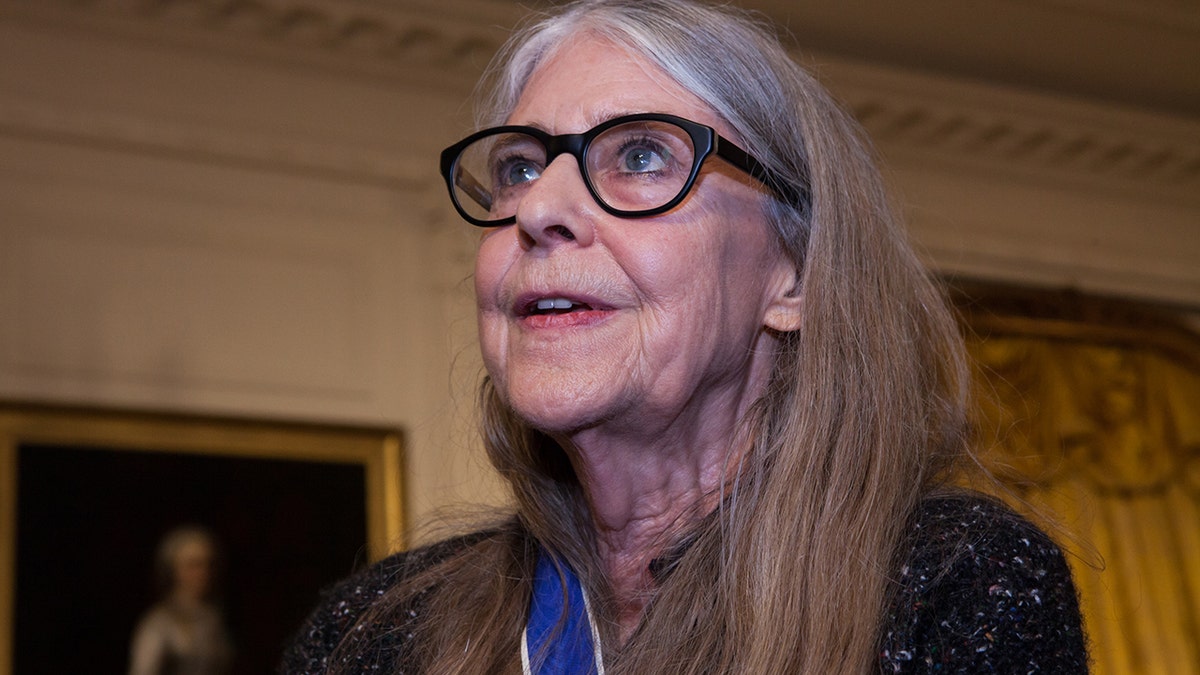

Margaret Hamilton is now in her late 80s. She ran her own software companies after completing her work with NASA in the 1970s.

She has rarely given interviews in her career. She did not respond to requests from Fox News Digital for this article.

President Barack Obama awards the Presidential Medal of Freedom to NASA mathematician and computer software pioneer Margaret Hamilton during a ceremony at the White House on Nov. 22, 2016, in Washington, D.C. Obama presented the medal to 19 living and two posthumous pioneers in science, sports, public service, human rights, politics and the arts. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

"We had to find a way and we did," Hamilton told MIT News in 2009 of her effort as a young computer scientist to help humankind break the bounds of earth.

"Looking back, we were the luckiest people in the world; there was no choice but to be pioneers."

She’s become something of an unwilling celebrity in the wake of her 1969 photo making the rounds on social media — the recognition long overdue for her many fans of today.

"Looking back, we were the luckiest people in the world; there was no choice but to be pioneers." — Margaret Hamilton

Hamilton was honored by President Obama with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2016, alongside fellow American luminaries Tom Hanks, Michael Jordan, Bruce Springsteen and others.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR LIFESTYLE NEWSLETTER

She earned pop-culture acclaim the following year, when Lego released its Women of NASA set, featuring Hamilton along with female space pioneers astronauts Mae Jemison and Sally Ride and former NASA chief astronomer and "Mother of Hubble" Nancy Roman.

Hamilton was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 2022.

She continued to work on NASA software right up through the Skylab, the first U.S. space station, in 1973. Her work powered the five moon landings that followed Apollo 11.

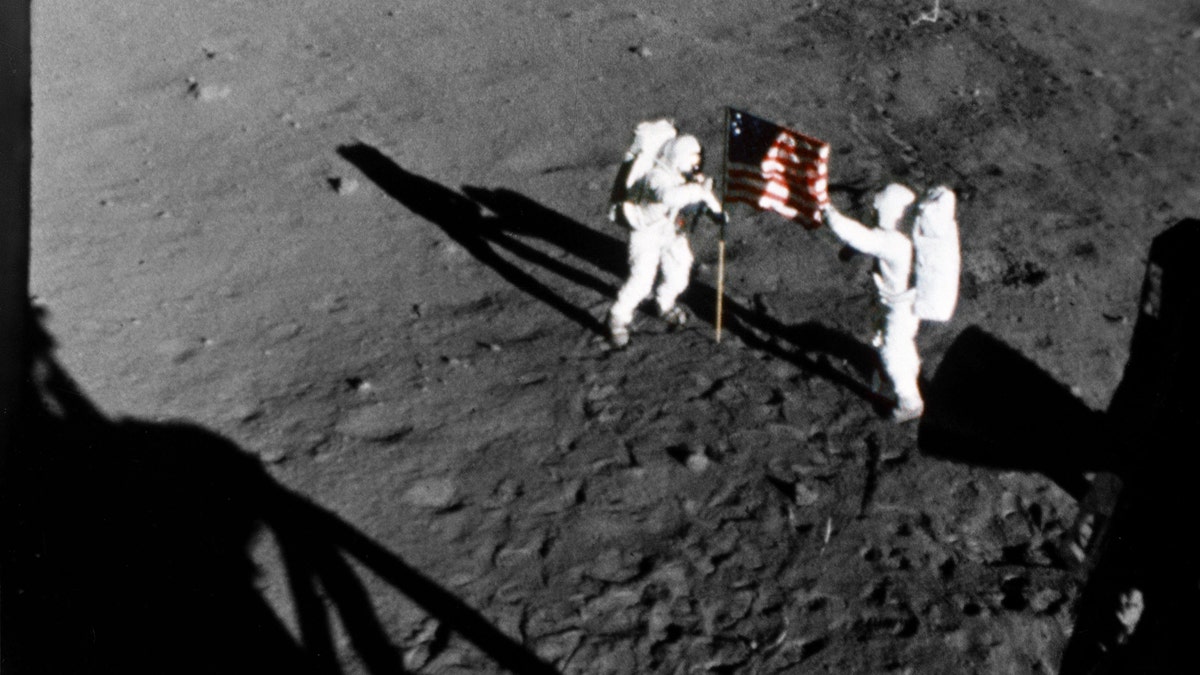

Astronaut Neil A. Armstrong stands on the left at the flag's staff. Astronaut Edwin E. Aldrin Jr. is also pictured. Picture taken by the 16mm Data Acquisition Camera (DAC) mounted in the LM deploy flag. (HUM Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

The last of them, Apollo 17, took place in Dec. 1972.

No man — or woman — has reached the moon since.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

"There is this old cliché in the space program," said NASA historian Odom. "If you want to know how difficult it was to put men on the moon, just try doing it again."

Margaret Hamilton, inset, along with some of the most iconic U.S. moon landing images. (NASA; Alamy)

(NASA is aiming to land astronauts on the moon in the next few years as part of the Artemis program.)

To read more stories in this unique "Meet the American Who…" series from Fox News Digital, click here.

For more Lifestyle articles, visit www.foxnews.com/lifestyle.