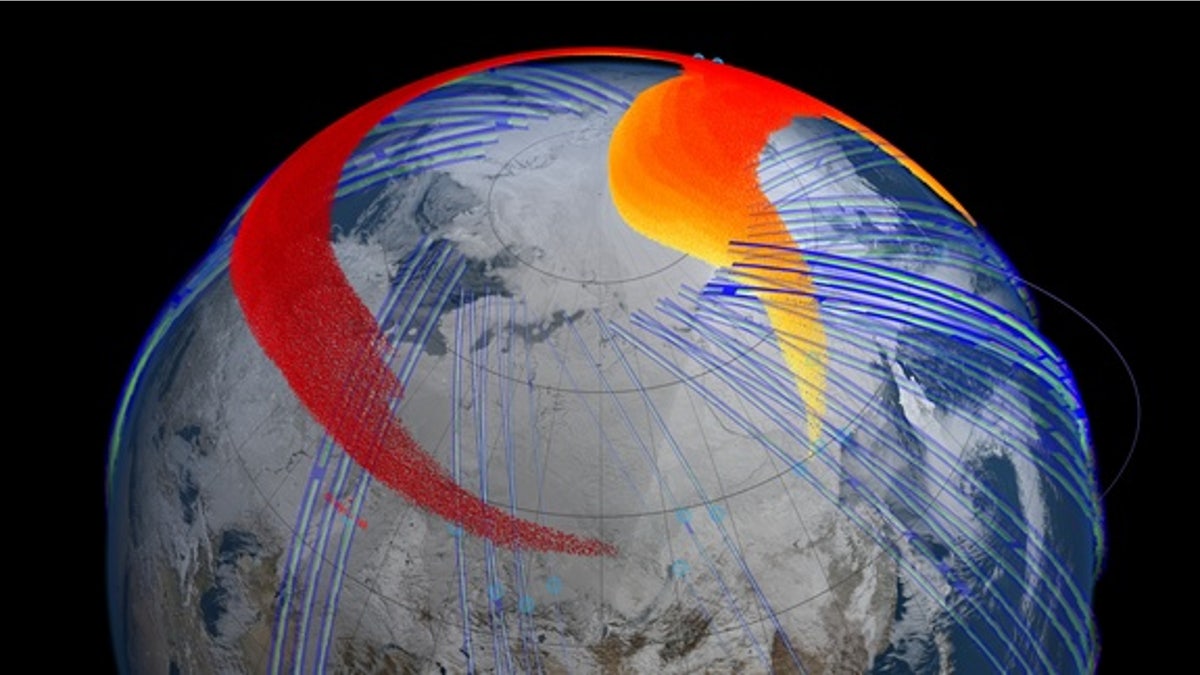

A portion of Chelyabinsk's dust plume circled Earth in just four days, as shown in this image based on modelling and the NPP Suomi satellite's observations (NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization)

When a meteor exploded over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk in February, pieces of the bus-sized space rock hit the ground while its detonation shattered windows, set off car alarms and injured more than 1,000 people.

Masked in the chaos, however, was an enormous plume of dust that the Russian meteor left behind in Earth's atmosphere. This cloud, which had hundreds of tons of material in it, was still lingering three months after the Feb. 15 explosion, a new study has found. Scientists created a video of the Russian meteor explosion's dust cloud to illustrate the phenomenon.

[pullquote]

"Thirty years ago, we could only state that the plume was embedded in the stratospheric jet stream," Paul Newman, chief scientist for NASA Goddard Space Flight Center's atmospheric science lab, said in a statement. "Today, our models allow us to precisely trace the bolide and understand its evolution as it moves around the globe." [See photos of the Feb. 15 Russian fireball]

Chasing dust

The Russian meteor, which weighed 11,000 metric tons when it hit the atmosphere, detonated about 15 miles above Chelyabinsk. The explosion sent out a burst of energy 30 times greater than the atom bomb that leveled Hiroshima during World War II.

Some of the asteroid's remnants crashed to the ground, but hundreds of tons of dust remained in the atmosphere. A team led by NASA Goddard atmospheric physicist Nick Gorkavyi, who is from Chelyabinsk, wondered if it was possible to track the cloud using NASA's Suomi NPP satellite.

"Indeed, we saw the formation of a new dust belt in Earth's stratosphere, and achieved the first space-based observation of the long-term evolution of a bolide plume," Gorkavyi said in a statement.

Initial measurements 3.5 hours after the meteor explosion showed the dust 25 miles high in the atmosphere, speeding east at 190 mph.

Russian officials were still cleaning up in Chelyabinsk when, four days after the explosion, the higher portion of the plume reached all the way around Earth's northern hemisphere. Even three months into the study, Suomi still saw a "detectable belt" of dust circling the globe, researchers said.

Putting it in perspective

Tracking the plume also revealed some insights into how particles behave in Earth's atmosphere. Heavier particles, for example, moved more slowly as they dropped closer to Earth in an area with lower wind speeds. Lighter particles maintained speed and altitude, consistent with predictions of wind velocities at their heights.

While the plume was easily detectable, it was by no means extraordinarily dense, NASA researchers noted. About 30 metric tons of space dust hits the Earth every day on average. Also, volcanoes and other natural Earth sources contribute far greater numbers of particles to the stratosphere.

The study is ongoing, with potential research directions including looking at whether or not meteor debris can affect cloud formation in the stratosphere and mesosphere.

A paper based on the work so far has been accepted for publication in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.