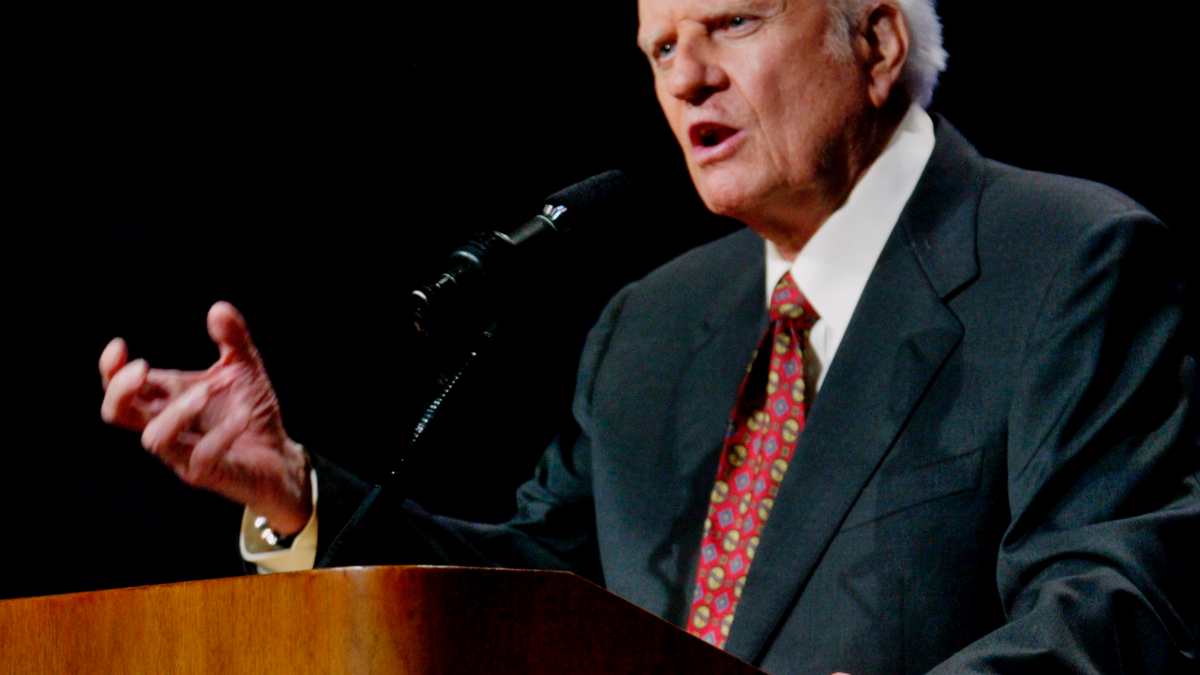

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. – The Rev. Billy Graham was single-minded when he preached about God, prefacing sermon points with the phrase "The Bible says ..." Yet he had a complicated role in race relations, particularly when confronting segregation in his native South.

In Alabama for one of his evangelistic crusades in 1965, just months after passage of the Civil Rights Act, Graham talked about the Confederate flag flying "proudly" atop the state Capitol and the fact that both of his grandfathers served as rebel soldiers, according to a recording available on his ministry's website. He didn't address the evils of segregation directly, talking instead about God's unique power to change people and communities.

But Graham also drew scorn from segregationists for speaking to racially mixed crowds and allowing blacks and whites to mingle during the trademark altar call that ended each service. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was an ally, and King publicly credited Graham with helping the cause of civil rights.

As a white moderate who spoke with a Southern drawl, Graham helped ease the region's transition away from legalized segregation, said Steven P. Miller, a scholar who has written about Graham. Graham had a "huge base" of white support in the Bible Belt, Miller said, and those people listened to him.

"He could reach that audience as a native Southerner, but also because he spoke a familiar evangelical language — and because he was obviously not an activist," said Miller, author of the book "Billy Graham and the Rise of the Republican South."

"Ultimately, what Graham put forth was what we might now call a colorblind gospel," Miller said via email. "In this sense, he provided a familiarly Christian path for some white Southerners to back away from Jim Crow."

A current civil rights leader from Graham's native North Carolina, the Rev. William J. Barber II, credited Graham with meeting with King and agreeing to challenge segregation, an act Graham pursued through preaching reconciliation and peace rather than marching.

"Billy Graham inherited a faith in the American South that had accommodated itself to white supremacy, but he demonstrated a willingness to change and turn toward the truth," Barber said in a Facebook post after Graham's death. "He helped to tear down walls of segregation, not build them up."

Still, Graham had regrets. In an interview with The Associated Press in 2005, when he held his final crusade, Graham said he wished he had fought for civil rights more forcefully. In particular, Graham lamented not joining King and other pastors at voting rights marches in Selma, Alabama, in 1965.

"I think I made a mistake when I didn't go to Selma," Graham said. "I would like to have done more."

Graham also apologized for making anti-Semitic remarks that were captured on the White House taping system installed by President Richard Nixon, who relied on Graham for both spiritual needs and political cover. The relationship between the two men helped turn the South into the solidly Republican territory it is today, Miller argues in his book.

Born in 1918 on the family farm near Charlotte, North Carolina, Graham grew up in a South strictly divided by race. In an act that sounds mundane now but was perilous at the time, he demanded the removal of ropes separating black and white audience members at a crusade in the South in the early 1950s.

Graham was an internationally known preacher traveling the world by 1955, when King first gained notice by leading a bus boycott against segregation in Montgomery, Alabama. Graham embraced King's work, and the two appeared on stage together during a Graham crusade at New York's Madison Square Garden in 1957. Graham paid the jail bond following King's arrest during demonstrations in Albany, Georgia, in 1962.

Following the racial violence of "Bloody Sunday" in Selma in 1965 and partly at the suggestion of President Lyndon B. Johnson, Graham toured Alabama, speaking to racially mixed crowds. It was during that trip that he recorded the message in which he spoke wistfully of his Confederate roots and God's ability to heal.

While Graham didn't march with King in Selma, the Atlanta-based King Center for Non-violent Social Change credits Graham with evolving from an early, noncommittal stance on race following the Supreme Court's 1954 decision outlawing segregation in public schools.

Barber said Graham also eschewed the religious right movement, which many Southern evangelicals embraced on the way toward increasing their political power after the Nixon years.

"His life was about following Jesus, and he knew that meant an ongoing commitment to be changed by love," Barber said.