Surge in child fentanyl poisonings 'just the beginning' of fentanyl crisis

A new study shows children are dying of fentanyl poisonings at a faster rate than any other age group.

The longtime suspect in the 1982 Tylenol murders that killed seven people in three days, sparking nationwide panic, has died, police said.

James Lewis died at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on Sunday at age 76.

"Following an investigation, Lewis’ death was determined to be not suspicious," Cambridge Police Superintendent Frederick Cabral said in a statement.

More than four decades ago, Mary Kellerman, 12, was the first to die and followed by six more people in the Chicago area after taking a dose of the then-best-selling nonprescription pain reliever.

THE TYLENOL MURDERS: A LOOK BACK AT THE RASH OF 1982 DRUG STORE POISONINGS

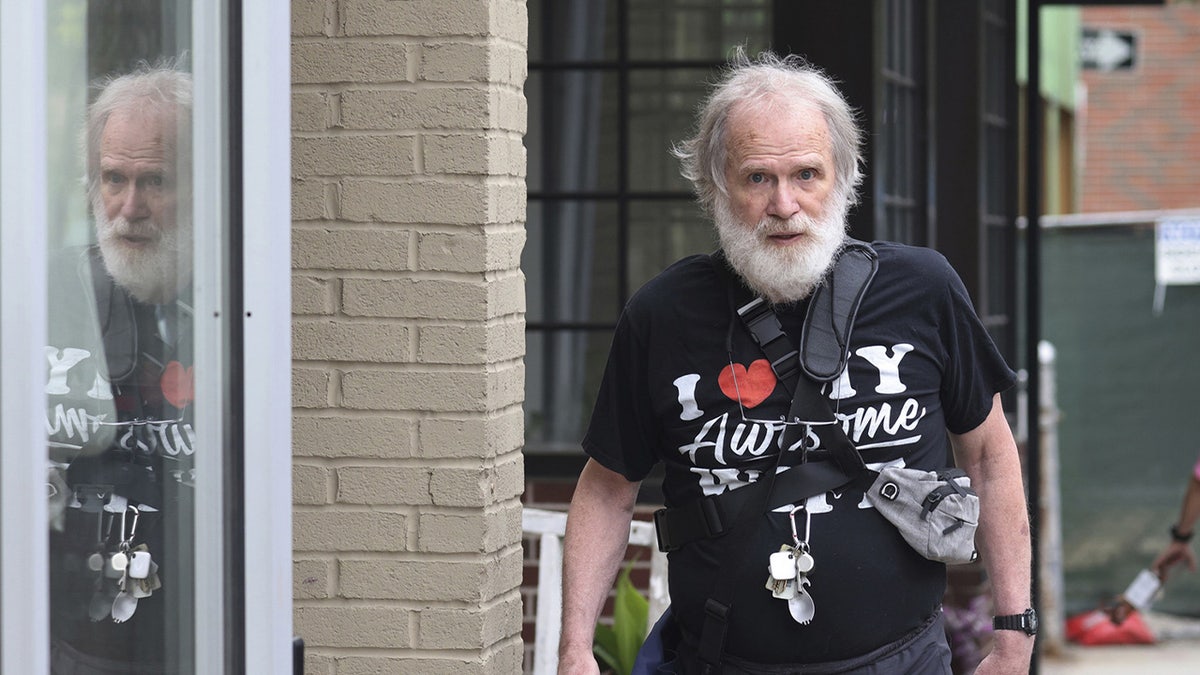

The longtime suspect in the 1982 Tylenol murders, James Lewis, died Sunday at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, police said. (Yvonne Hemsey via Getty Images | Charles Krupa via AP)

Investigators soon realized that each victim had swallowed a tablet laced with a lethal dose of cyanide. The pill manufacturer, Johnson & Johnson, determined that the bottles had been tampered with after leaving the factory.

Someone had taken the bottles off the shelves at several drug stores, added poison to the capsules and then put them back.

Although no one was ever charged for the deaths, Lewis sent an anonymous extortion letter to Johnson & Johnson, demanding $1 million to "stop the killings."

A nationwide manhunt culminated in Lewis' arrest in New York City in 1982, but he denied he was responsible.

James Lewis, 76, walks in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Some investigators have renewed their efforts to pin the Tylenol murders on Lewis, who was convicted of sending an extortion letter to manufacturer Johnson & Johnson but has repeatedly denied being the Tylenol killer. (Stacey Wescott / Chicago Tribune / Tribune News Service via Getty Images)

He admitted sending the letter but said he'd only wanted to embarrass his wife's former boss by having the money put in the employer's account. He was convicted of extortion and served more than 12 years in prison.

But investigators couldn't pin the murders on Lewis, and he remained the prime suspect. In 2009, the FBI seized a computer and other items from his home after launching a fresh probe into the mysterious poisonings.

SOCIAL MEDIA IS LINKED TO CARTELS, FENTANYL: ANNE MILGRAM

It wasn't the first time Lewis found himself the target of a criminal investigation. In 1978, he was charged in Kansas City, Missouri, with the murder and dismemberment of Raymond West, who had hired him as an accountant.

The charges were later dismissed, in part, because some evidence was obtained illegally.

In 2004, he was charged with the rape and kidnapping of a Cambridge woman. After spending three years behind bars awaiting trial, the charges were dismissed when the victim refused to testify against him.

Foil safety seals became standard on all over-the-counter medications after the 1982 Tylenol murders. (Daniel Acker / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Many investigators still believe Lewis is behind the murders, but three Chicago police detectives told the Chicago Tribune in 2022 that an old suspect, amateur chemist Roger Arnold, is the likely culprit.

Authorities amassed a mountain of circumstantial evidence against Arnold – including admissions that he wanted to poison people and his connections to the drug stores that sold the tainted pills. But there wasn't enough evidence for an arrest.

The FBI wasn't on board, according to the newspaper, and when the ransom letter came in, the agency switched gears and focused on Lewis.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

After the Tylenol murders, the FDA created federal guidelines that require medication manufacturers to use tamper-resistant bottles with foil seals to make it easy for consumers to tell whether a container has been altered.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.