CUCUTA, Colombia – As the crisis in Venezuela's socialist dictatorship deepens – gripped by mass hunger, starvation and a lack of medical supplies - there is no comfort even for the dead.

“What is happening is medieval. People are ‘renting’ caskets for a service, but giving them back. The same casket is being used over and over again because people cannot afford to buy one,” Venezuelan opposition leader Julio Borges, who has been living in exile in the Colombian capital of Bogota for the past nine months, told Fox News. “And then they have to wrap the body in plastic bags for the burial. Others don’t have money for a land plot, so they are burying loved ones in their back garden.”

Borges said the “really creepy” problem of how to properly bury the dead has become the norm rather than the exception. Other Venezuelans concurred, indicating the use of “common graves,” along with backyard burials, was becoming standard.

One Venezuelan, who asked his name not be published, described the sudden death of his father in the capital Caracas last week, which left the family without a vehicle to take the body to the morgue. It took more than a day for the body to be collected.

Atilio Gonzalez (C), a priest of the Southern Cemetery for the last 24 years, prays during a burial ceremony at the Southern Cemetery in Caracas January 28, 2014. Since then, proper burials have become too expensive for the vast majority of the population.

And even then, the family had to say their goodbyes – they had no money for a funeral, or burial – praying the body would be disposed of in some kind of mass cremation.

For every day a body remains in the morgue, the cost rises, leaving families without the means for collection. In such cases, loved ones are simply left stranded – their relatives in mourning, not knowing what to do, and without closure.

“Funeral services are too expensive. Coffins are expensive, as well as paying for a place in the cemetery and everything that comes with it: the chapel for the service, the plate,” Julett Pineda, a health journalist for Efecto Cocuyo in Caracas, told Fox News. “People cannot have a decent funeral.”

Venezuelan opposition leader Julio Borges, who has been living in exile in the Colombian capital of Bogota.

Pineda recounted stories of parents who have tried to collect and earn money for the funerals of their own children. But as the economy of the cash-strapped nation continues to deteriorate, all they can afford is the cremation, which costs roughly a third of burial costs.

INSIDE LATIN AMERICAN 'AMAZING RACE' STAR’S DRAMATIC ESCAPE FROM VENEZUELA

CHAPO MAY BE ON TRIAL, BUT HIS SINALOA CARTEL STILL DOING HUGE US BUSINESS

Pineda’s latest estimate is that funerals in Venezuela cost more than 132 times the average minimum wage earned per month. That's around six dollars per person – making a final farewell far out of reach for most who would need years of savings to cover costs.

“In poorer areas, plywood coffins are sometimes being used,” explained Guillermo Aveledo, a 40-year-old political science professor at the University of Caracas. “Former middle classes can rent a proper coffin for the wake, but prefer cremation, which is cheaper.”

But even the process of cremation has become problematic. Locals described to Fox News the acute lack of natural gas needed to properly incinerate the bodies, despite the fact Venezuela has some of the largest energy reserves in the world. “In some very isolated places, people get used lots for burial, which creates sanitary problems,” Aveledo said.

The shortage of hearses is also an issue. There are fewer and fewer of them available, and the acute fuel shortage - wait times at some gas stations can be as long as 24 hours - makes it harder to keep them running.

In some extreme cases, impoverished Venezuelans are dragging their dead for days in the sweltering sun to reach the Colombian border, where locals are assisting them with some kind of burial.

Alexander Lopez, a disabled Venezuelan from Maracaibo who has resorted to selling keychains, incense, and trash bags for a few cents each in the Ecuadorian town of Cuenca, fled Venezuela six months ago. He left to find work to pay for his 19-year-old son and 11-year-old daughter, saying he could no longer sit by as his family was forced to scour through the trash for food.

Alexander Lopez, now working on the streets in Cuenca, Ecuador struggled to send money back to his native Venezuela to retrieve his son's body.

Tragically, his son Alexander was killed in a motorcycle accident on the small Venezuelan island state of Nueva Esparta two months ago. For weeks, the body languished at the morgue as family members were unable to afford the bus fare and boat to collect the remains. Lopez’s former wife, Alexander’s mother, was eventually able to use some law enforcement connections to help cobble together the money needed.

But when she got to the morgue, the owners would not release the body - demanding a bribe on top of the standard costs. “Everyone in Venezuela is so desperate for money, even the morgue will manipulate the people,” Lopez wept, holding up his son’s photograph.

After being killed in a motorcycle accident, the body of Alexander Lopez spent several weeks in a Venezuela morgue, as his family struggled to come up with the money needed to retrieve him.

For days, Lopez said, his wife trolled the streets and he and others sent whatever funds they could to pay the $150 morgue fee - an amount that far surpasses an average month’s earnings.

After the entire family hustled for further $88 to pay a local gravedigger, Alexander was finally laid to rest in a cemetery. There were no funds for a service, no memorial plaque or tombstone.

“Even with all that,” Lopez said softly, “the dead in Venezuela are still worth more than the living. I am worth nothing to that government.”

Lopez’s story is woven with even more tragedy. Three years ago, as the crisis accelerate, he was injured in a motorcycle accident. His wounded leg became infected a year later, but the lack of affordable medicines and medical professionals led to the loss of his leg, which was amputated.

“All they could do was cut it,” he said, motioning to where his right leg used to be.

Families in Venezuela have been forced to resort to backyard burials (Fox News (provided))

That lack of medical attention and resources has fueled a spiking death rate in Venezuela. People are dying today from the most common and treatable infections and diseases - like the common flu.

Violent crime is also on the rise. Last week, two ex-major league baseball players - free agent Luis Valbuena and former player Jose Castillo - were killed in a crash after their car collided with a rock. Authorities believe the rock may have been deliberately placed in the road, as part of a robbery scheme.

“People throw rocks in the hope of stopping the car so they can steal it,” one Venezuelan humanitarian worker explained. “In this case, it ended horribly... Even if these men had survived, there are not adequate means in the hospital to save them.”

According to Aveledo, even the dead aren't immune to the rise in crime.

“Most cemeteries are public municipal lots. But the dearth of public safety exposes the tombs to looting, mourners, and visitors exposed to muggings, and wakes are restricted for a couple of hours during the day,” he said. “The wakes held for criminals are also very disruptive, public displays of their power and control of territories.”

As the country crumbles, so to have the resources to monitor how many have died. One local journalist said a handful of people try to keep tabs. A group of journalists visit the morgues at the end of each week to count the dead, trying to determine how many died from organized crime, and how many perished from “other” causes, like disease or malnutrition.

And that is just in Caracas. For the rest of the country that once had a population of 32 million, it’s anybody’s guess.

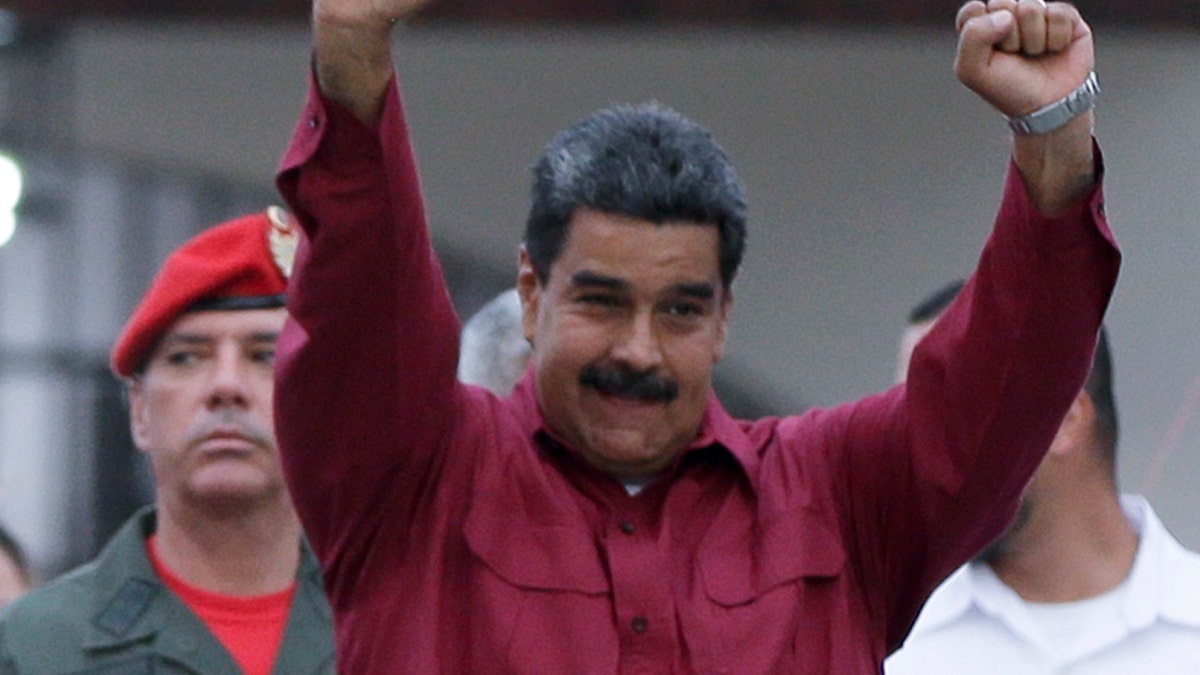

Venezuela's President Nicolas Maduro raises his fists after voting in presidential elections in Caracas, Venezuela, Sunday, May 20, 2018. (AP)

There's no indication the situation will improve any time soon. Despite once-brimming oil wealth that had Venezuela as the richest country in Latin America, the Nicolás Maduro-led government - which has continued the socialist policies of his predecessor, Hugo Chavez - has pushed the nation’s economy into dire freefall, upended by massive hyperinflation, food and medicine shortages. More than three million have fled in desperation since for crisis began spiraling out of control three years ago.

The government has denied that Venezuela is in crisis, and instead blames its economic woes on disgruntled opposition members, and the United States.

As for the death industry, like most things in Venezuela, a black market in coffins has emerged. This despite the scarcity of wood and other materials needed to make a casket.

“The price range of a coffin on the black market is about 50 to 100 dollars,” Aveledo said. “Sold on the web, or via messaging.”