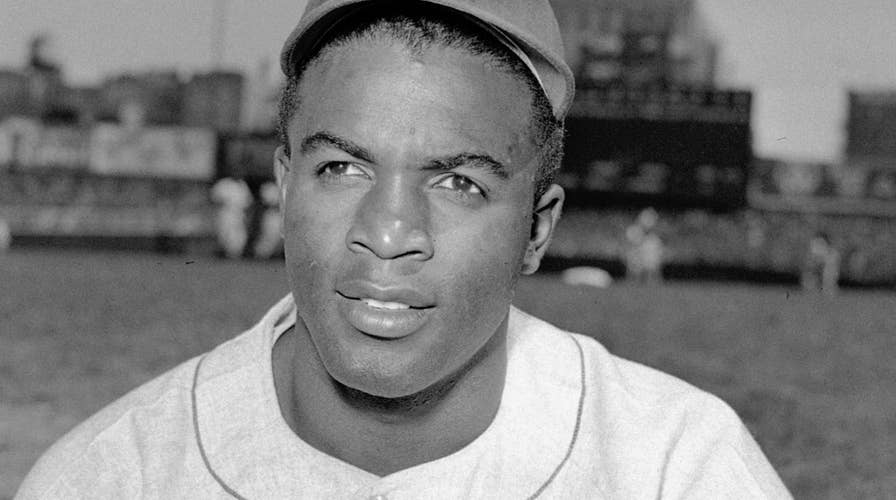

New book explores Jackie Robinson's faith

Fox News chief national correspondent Ed Henry pens '42 Faith: The Rest of the Jackie Robinson Story'

Shortly after Jackie Robinson was born on January 31, 1919, his mother Mallie held him while watching her husband and a slew of other Robinson family men try to make “sugar teats” – lard and sugar wrapped in cheesecloth to resemble nipples. They would supposedly ease Jackie’s assimilation into the world.

Mallie looked at the hapless guys as they spilled lard all over the floor, then at the meager home where five children now lived and whispered a simple blessing to young Jackie.

“Bless you, my boy,” she said. “For you to survive all this, God will have to keep his eye on you.”

ED HENRY: '42 FAITH' -- THE REST OF THE JACKIE ROBINSON STORY

Little did she know how true this would be for Jackie, who throughout his life would face down one obstacle after another on his way to breaking Major League Baseball’s color barrier on April 15, 1947.

Each of us has written a book about why, after years of research, we have come to the conclusion that the secret ingredient in Jackie’s success may very well have been the deep faith in God that was instilled in him at an early stage. “I never stopped believing that,” Robinson himself once said about the impact and importance of his faith.

Still, the stress of being “the first” – from people shouting racial epithets, to others threatening to gun him down because of the color of his skin – took its toll on Jackie. After his baseball days he battled blindness from diabetes, and died of a sudden heart attack in 1972.

From left, Brooklyn Dodgers baseball players John Jorgensen, Pee Wee Reese, Ed Stanky and Jackie Robinson pose at Ebbets Field in New York on April 15, 1947. (AP)

If Jackie Robinson was still living, he would be celebrating his 100th birthday later this week. To mark the occasion, the foundation that bears his name is launching a yearlong Jackie Robinson Centennial Celebration. There’s a major jazz concert in Jackie’s honor next month at his alma mater UCLA, and some special tributes at ballparks on Jackie Robinson Day in April, when every major leaguer already wears the number 42 in his honor.

All of this culminates in December, when Jackie’s surviving relatives will realize their dream of opening the new Jackie Robinson Museum in New York City, with the hopes of telling his inspiring story to future generations.

A key part of that story is how critical Jackie’s faith was in sustaining him in the low moments of his life, when lesser players – and lesser men – would have given up amid the barrage of racial attacks.

True, Jackie was aided tremendously by the courage of Branch Rickey, the general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who defied the rest of the baseball establishment to sign Jackie. Both men were Methodists.

But in an unpublished manuscript by Jackie that is featured in Ed Henry’s book, “42 Faith,” Robinson himself talks repeatedly about something much deeper that led him to success – an almost divine intervention that helped him defy the odds.

Robinson’s faith served as a source of inspiration and motivation, comfort and strength, wisdom and direction. It was the engine that drove and sustained him as he shattered racial barriers on and off the baseball diamond.

“Somebody else might have ... done a better job,” Robinson wrote. “But God and Branch Rickey made it possible for me to be the one, and I just went on in and did the best I knew how.”

Jackie’s story of faith began when Mallie Robinson left her philandering husband behind in rural Georgia. She moved her children to Pasadena, California when Jackie was 6-months-old, hoping to escape the oppressive bigotry of the Jim Crow South.

But discrimination existed everywhere, and young Jackie was infuriated by it. On top of that, he was being raised by a single mom, and he was going down the wrong path. He joined a gang in Pasadena and got involved in fistfights and scrapes with the law, prompted by racial antagonism.

And then one day, a young minister at the Scott United Methodist Church in Pasadena, Rev. Karl Downs, intervened. He told Jackie that all of his athletic talents would go to waste if he didn’t make a clean break from the gang. Rev. Downs sparked nothing short of a spiritual awakening in Jackie; he became a father figure and brought Jackie back into the church.

Two years after becoming the first African-American to play in the Major Leagues, Jackie Robinson (far left) along with Larry Doby, Don Newcombe and Roy Campanella became the first African-Americans to appear in an All-Star Game (AP)

“Often he would find a way of applying a story in the Bible to something that happened in real life,” Robinson noted about Downs. “He didn’t preach and he didn’t talk down like so many adults or view you from some holy distance. He was in there with you.”

Jackie even became a Sunday school teacher while attending UCLA – a sign of the impression Downs made on him. “I had a lot of faith in God,” Jackie would say later. “There’s nothing like faith in God to help a fellow who gets booted around once in a while.”

Jackie got more than just booted around once he trotted onto the baseball diamond at Ebbets Field for the Brooklyn Dodgers in April 1947.

Nobody in sports ever faced the pressure and abuse that Robinson did. Pitchers threw at his head – and virtually every other body part – to harm him. Base runners spiked him with their sharp cleats. Spectators called him the vilest of names. Violent threats came in the mail daily.

But Robinson’s faith served as a source of inspiration and motivation, comfort and strength, wisdom and direction. It was the engine that drove and sustained him as he shattered racial barriers on and off the baseball diamond.

Robinson’s wife, Rachel, who also is a Methodist, comforted her husband during his arduous journey. And she recalled that during that tough rookie year of 1947 he would get down on his hands and knees to pray before bed.

“It’s the best way to get closer to God,” he said of the nightly ritual.

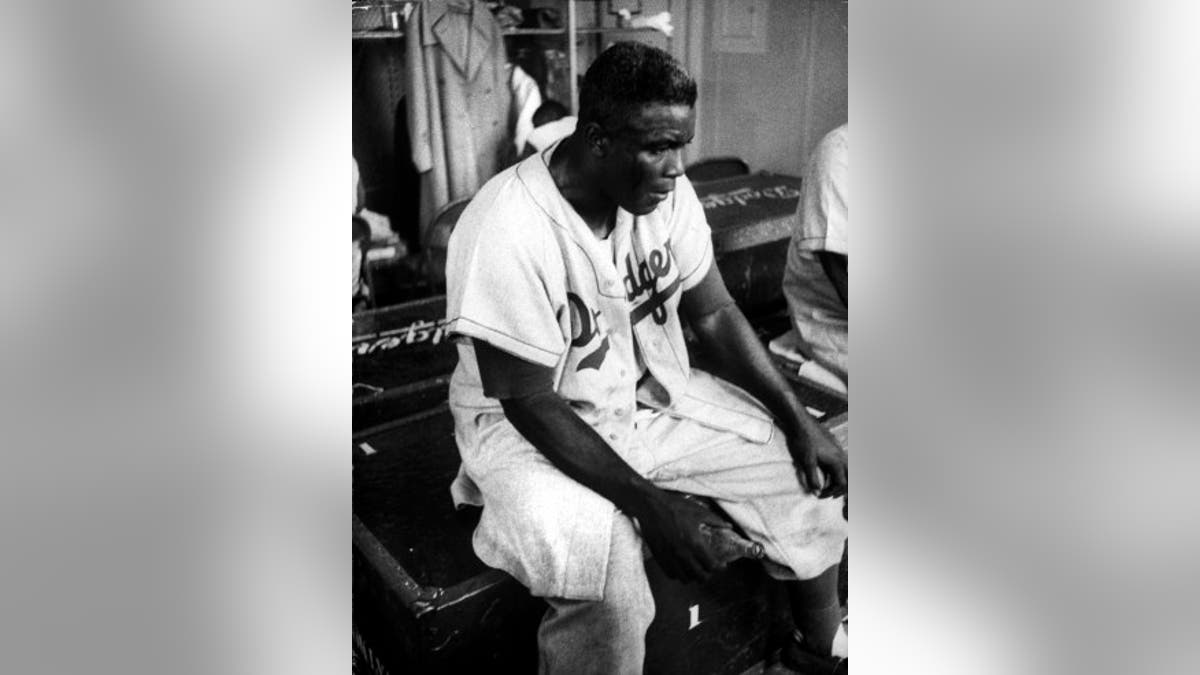

Jackie Robinson looks exhausted and dejected in the locker room after a game, May 12, 1955. (Francis Miller//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

As Chris Lamb and his co-author Michael G. Long show in their book, “Jackie Robinson: A Spiritual Biography,” Robinson’s faith was on display before he joined the Dodgers. While playing for the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro Leagues, Jackie openly scorned his whiskey-drinking and promiscuous teammates, once tossing a glass of scotch into a lighted fireplace to demonstrate how lethal liquor is. He also stunned some of his teammates by declaring that he was waiting until he was married to have sex.

But Robinson and Rickey were a perfect match. Rickey’s religious devotion was such that he didn't even attend Dodgers games on Sundays after making a solemn promise to his own mother many years earlier. She was worried there was too much sin around the game, so in exchange for allowing Rickey to pursue his dream of first playing and then serving as an MLB executive, he would never step foot in a ballpark on Sunday to keep his focus on the Lord.

When the two men first met at the Dodgers offices in the summer of 1945, Rickey told Robinson that he wanted to sign the 26-year-old ballplayer. But for Robinson to succeed, Rickey said, he couldn't respond to the indignities that would be piled on him. "I'm looking for a ballplayer with guts enough not to fight back."

Rickey then opened a book published in the 1920s, Giovanni Papini's "Life of Christ," and read Jesus' words: "But whoever shall smite thee on the cheek, turn to him the other also."

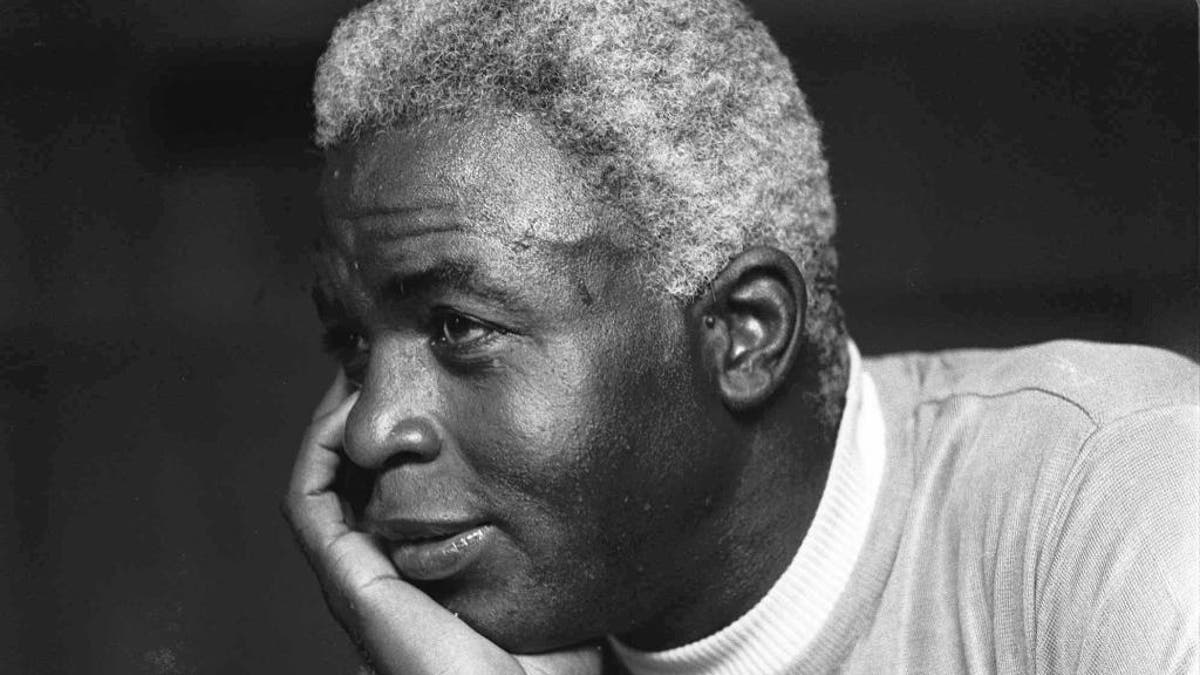

FILE - In this June 30, 1971, file photo, Jackie Robinson poses at his home in Stamford, Conn. (The Associated Press)

Robinson knew the Gospel and knew what was required of him. “I've got two cheeks, Mr. Rickey,” he said.

Rickey would later declare that Robinson was “almost Christ-like” in his ability to rise above it all.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

But Robinson was also human enough to admit that there were plenty of times he wanted to punch out his oppressors. "I can testify to the fact that it was a lot harder to turn the other cheek and refuse to fight back than it would have been to exercise a normal reaction," Robinson wrote. "But it works, because sooner or later it brings a sense of shame to those who attack you. And that sense of shame is often the beginning of progress."

A worthy lesson for all of us at a time of great division in America. Happy Birthday, Mr. Robinson.

Chris Lamb, a journalism professor at Indiana University-Indianapolis, is co-author of “Jackie Robinson: A Spiritual Biography.”