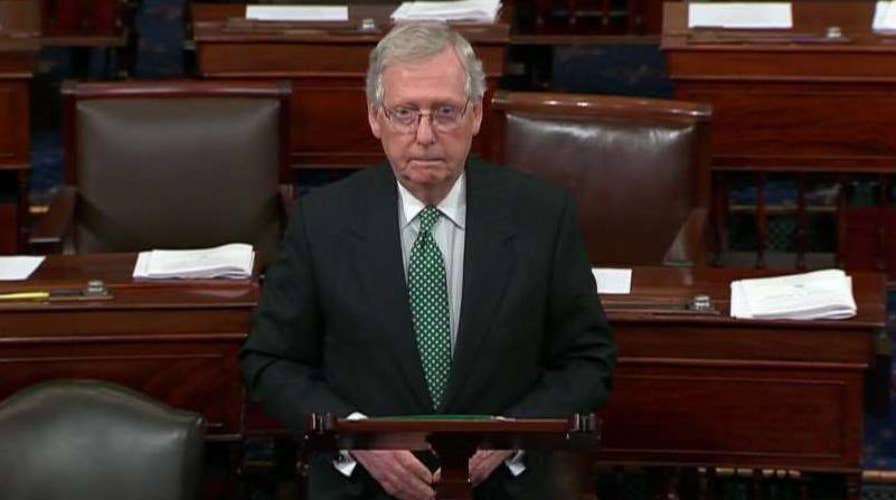

Senator McConnell takes first step towards Kavanaugh vote

Senate Majority Leader McConnell announces Senate will receive FBI report on Kavanaugh; Chad Pergram shares latest details from Capitol Hill.

There’s a lot which could go wrong for Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., as he tries to usher the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh for the Supreme Court to confirmation.

And so McConnell’s been trying to avoid those pitfalls since the end of last week.

It started with little fanfare Friday night when McConnell managed to formally start Senate debate on Kavanaugh’s nomination. And then, before dimming the lights for the weekend, McConnell “recessed” the Senate until Monday.

The Senate did not “adjourn.”

There is a key procedural difference between adjourning and recessing the Senate, even though it looks the same to the untrained eye.

On Monday, McConnell again “recessed” the Senate until Tuesday. But the Kentucky Republican did not “adjourn” the Senate.

Same thing Tuesday and Wednesday. On Tuesday, the Senate “recessed” until Wednesday. It did not “adjourn.”

Why the difference?

McConnell is trying to streamline the process on Kavanaugh as much as he can.

If the Senate hasn’t “adjourned” for the day, it’s still the “old day.” In other words, in the Senate’s space-time continuum, it’s essentially last week. It didn’t roll over to this week. The Senate has only “recessed” multiple times since Friday. The Senate has yet to move on.

The maneuvers by McConnell may not mean much to the casual observer. But recessing the Senate, rather than adjourning the Senate helps McConnell smooth the path as much as he can on the Kavanaugh nomination.

When the Senate meets each day, it addresses a docket of quotidian administrative issues. The list includes the introduction of bills, reports from committees, messages from the House, approval of the Journal, you name it. The Senate usually agrees to these items in a rote, mechanical fashion. But when things are as supercharged as they are now with Kavanaugh, menial, daily tasks are packed with the potential for mischief for Democrats to attempt to sidetrack the nomination.

So, by not adjourning the Senate for days, McConnell doesn’t have to wrestle with possible dilatory tactics from the Democrats.

The Senate considers Supreme Court nominations on what’s called the “executive” calendar. Senators address garden variety bills on the “legislative” calendar. However, McConnell must obtain the agreement of all 100 senators (called securing “unanimous consent’) to go back and forth between executive and legislative session

Recessing the Senate simply obviates the need to dip in and out of executive session and legislative session. If McConnell toggled back and forth between the two, there’s a chance the Senate could get caught in legislative session. Democrats could try to block McConnell and impede the GOP from returning to executive session to deal with Kavanaugh.

So, with few watching on Friday night, - and an initial agreement with Democrats that they wouldn’t object - McConnell slid the Senate into executive session to launch debate on the Kavanaugh nomination. But, there was a problem. The Senate still had to synchronize with the House of Representatives on a bill to reauthorize the FAA on a long-term basis. Also in the queue was a bipartisan measure to combat opioid abuse. The Senate couldn’t approve those bills while in executive session. So McConnell engineered a plan to keep the Senate in executive session. From a technical standpoint, the Senate would remain on the Kavanaugh nomination. But the Senate could now simultaneously wrestle with the FAA bill and the opioid bill “as though in legislative session.”

It’s not unprecedented for the Senate to engage in such parliamentary illusions. If this were the NFL, commentators would say McConnell was playing a “prevent defense.” McConnell simply designed a gambit to handle all three issues at once and protect his primary concern: advancing the Kavanaugh nomination with as few disruptions possible.

On Wednesday, the Senate approved the FAA bill 93-6. A few hours later, the Senate okayed the opioid legislation 98-1.

Then it was back to Kavanaugh.

McConnell repeatedly stated that the Senate would vote “this week” to confirm Kavanaugh. And late on Wednesday night, McConnell commenced a procedural arpeggio to tee-up a confirmation vote Saturday.

The most-cherished privilege of all senators is unlimited debate on the floor. However, the Senate can vote to curb debate and cut off senators if it “invokes cloture,” the parliamentary mechanism to impede filibusters. Cloture is a little bit like “closure.” Just transpose the “s” for a “t.”

So, at 9:54 p.m. ET Wednesday, McConnell filed a “cloture petition” to halt debate on the Kavanaugh nomination.

By rule, a cloture petition must lay over untouched for an entire day before it “ripens” and is ready for a procedural vote. By filing before midnight, McConnell got the petition in under the wire. Thursday serves as the “layover” day for the cloture petition.

Senate rules also provide for the Senate to vote on cloture one hour after the Senate meets. If the Senate really tries to maximize its time, senators could start the Senate day at 12:01 am et on Friday. Thus, the cloture petition to draw debate to a close would “ripen” at 1:01 am et Friday and be available for a procedural vote. This requires 51 votes. If the Senate votes to “invoke cloture” or limit debate, opponents of the nomination then get 30 hours to run out the string. But only 30 hours. That’s it.

McConnell faced a potential filibuster in the spring of 2017 when the Senate considered the nomination of Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch. McConnell was unable to alter the Senate rules. So, McConnell established a new “precedent” in the Senate. It used to take 60 votes to end debate on a Supreme Court nominee. So McConnell lowered the bar to break a filibuster on a Supreme Court nominee from 60 yeas to 51 yeas.

If the Senate votes to invoke cloture and draw debate on Kavanaugh to a close on Friday, the 30 hours afforded opponents of the nomination will expire on Saturday. Once the 30 hours runs out, the process culminates in a confirmation vote on Kavanaugh. Confirmation requires a simple majority.