Mamie Smith recorded the first blues hit 'Crazy Blues' — here is her amazing story

Vaudeville performer Mamie Smith recorded "Crazy Blues" in 1920. It proved a huge hit and changed music all over the world, most notably helping to inspire rock 'n' roll.

Mamie Smith set the tone for a new century of sound in global music.

The Cincinnati native was the first singer to record the blues.

It’s the foundational American music form upon which jazz, country, rhythm and blues and, most notably, rock ‘n’ roll are built.

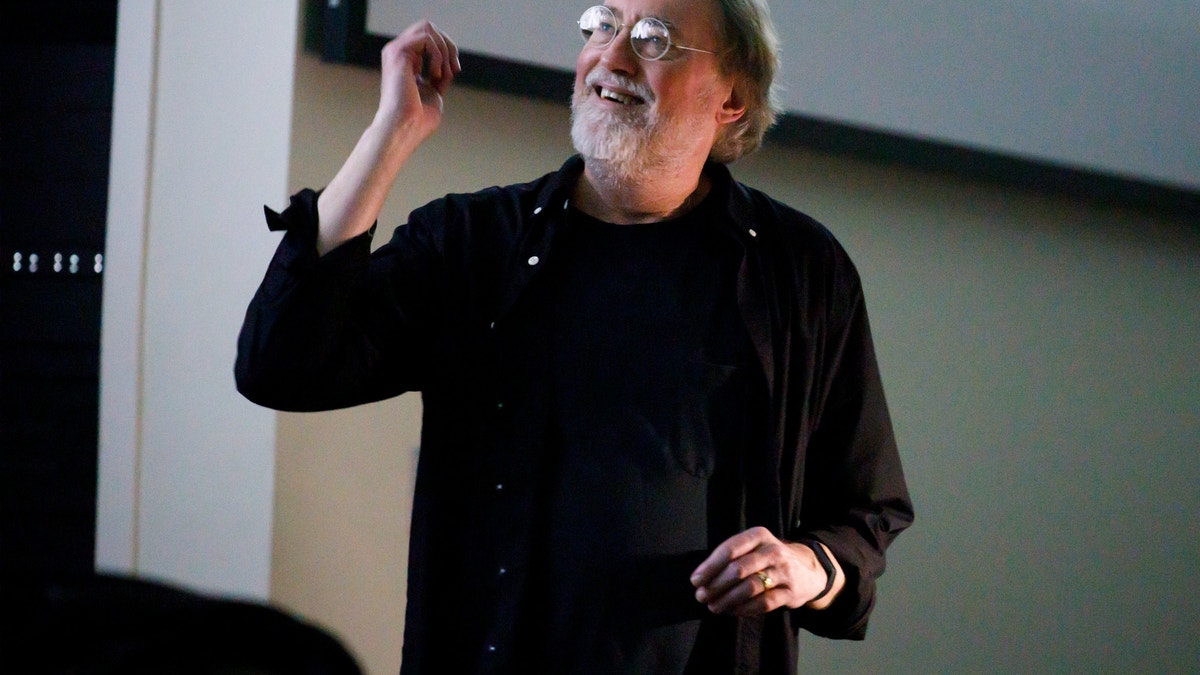

"The blues are America’s gift to the world," Indiana University professor emeritus and rock ‘n’ roll historian Glenn Gass told Fox News Digital.

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO INVENTED BAND-AIDS: COTTYON BUYER AND DEVOTED HUSBAND EARLE DICKSON

Smith wrapped the gift of raw American blues in a tidy bow of polished pop professionalism. She was the first artist to share music of the Mississippi Delta with a mainstream audience.

Her landmark recording was called "Crazy Blues."

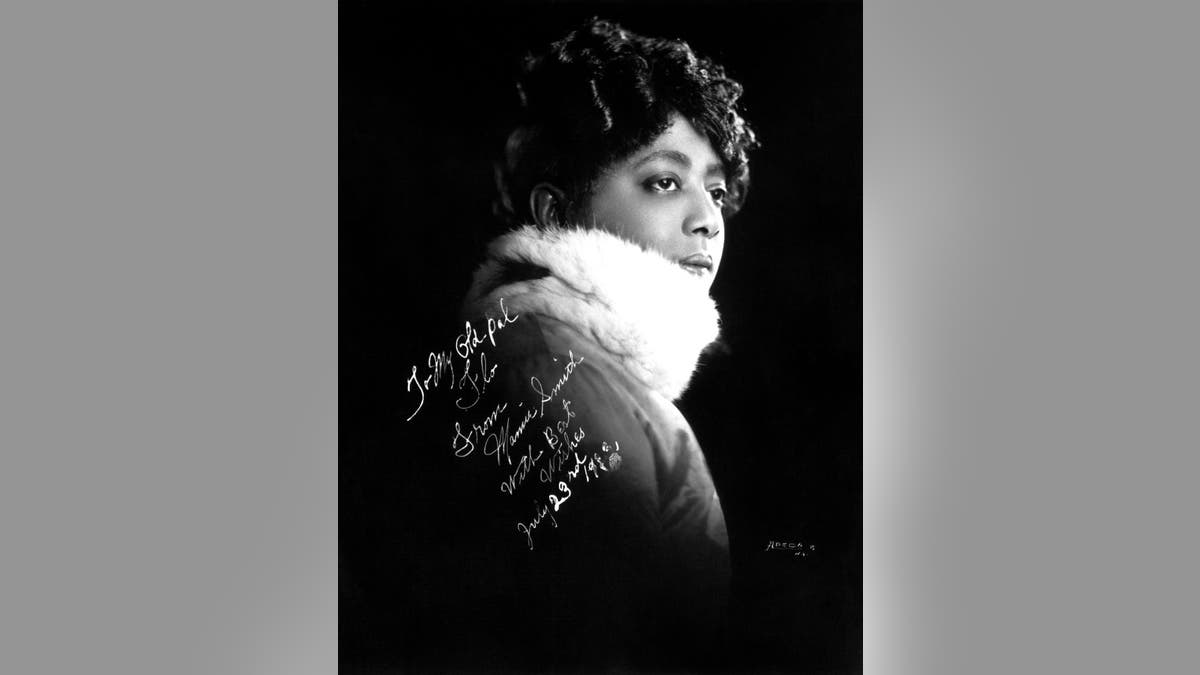

Jazz and blues singer Mamie Smith poses for a portrait in New York City circa 1920, the year she recorded the first blues hit, "Crazy Blues." (Donaldson Collection/Getty Images)

"I can't sleep at night/I can't eat a bite/'Cause the man I love/He don't treat me right," Smith laments, the tale of heartbreak and rhyming cadence familiar lyrical signatures of the blues.

The genre has proven its universal appeal.

She laid down the track with the backing band Her Jazz Hounds for OKeh records at 25 West 45th St. in Manhattan on August 10, 1920.

It sold 75,000 copies in its first month alone and generated up to $1 million in revenue for the label, according to various reports. It was a phenomenal figure for the era.

"I can't eat a bite/'Cause the man I love/He don't treat me right." — Mamie Smith, "Crazy Blues"

Smith has been dubbed the Queen of the Blues and, by many accounts, was America’s first pop diva. She rode the fame of "Crazy Blues" into several follow-up hits, a career in film and a lavish lifestyle.

She also opened the door for generations of artists to follow. "Crazy Blues" proved to record executives that there was a market for music by Black performers and a vast audience of African-American consumers with disposable income.

Yet, as if living her own tale of the blues, Smith died broke in 1946.

She was buried in an unmarked grave on Staten Island, New York, before grateful fans honored her with a headstone in 2014.

The influence of Smith’s recording far outlasted her fame or her time on Earth.

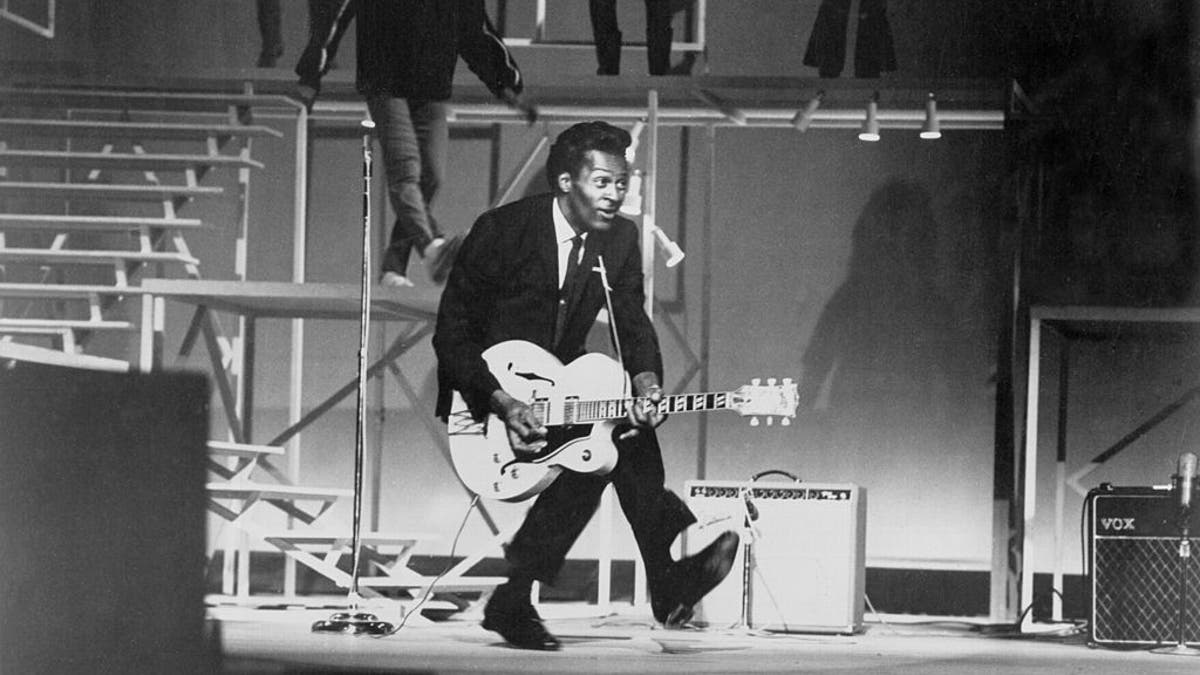

Within a decade of her death, American artists such as Chuck Berry, Bill Haley and Elvis Presley offered up a raucous new form of the blues that inspired a pop-culture frenzy.

"The blues had a baby and they named it rock ‘n’ roll," musician Muddy Waters crowed in 1977.

The blues soon crossed the Atlantic Ocean.

Its later guitar-driven sound, its bent notes and syncopation, its stories of outcasts and misfits battling life, loss and love all dug deep into the souls of a generation of disaffected teens in struggling post-war Great Britain.

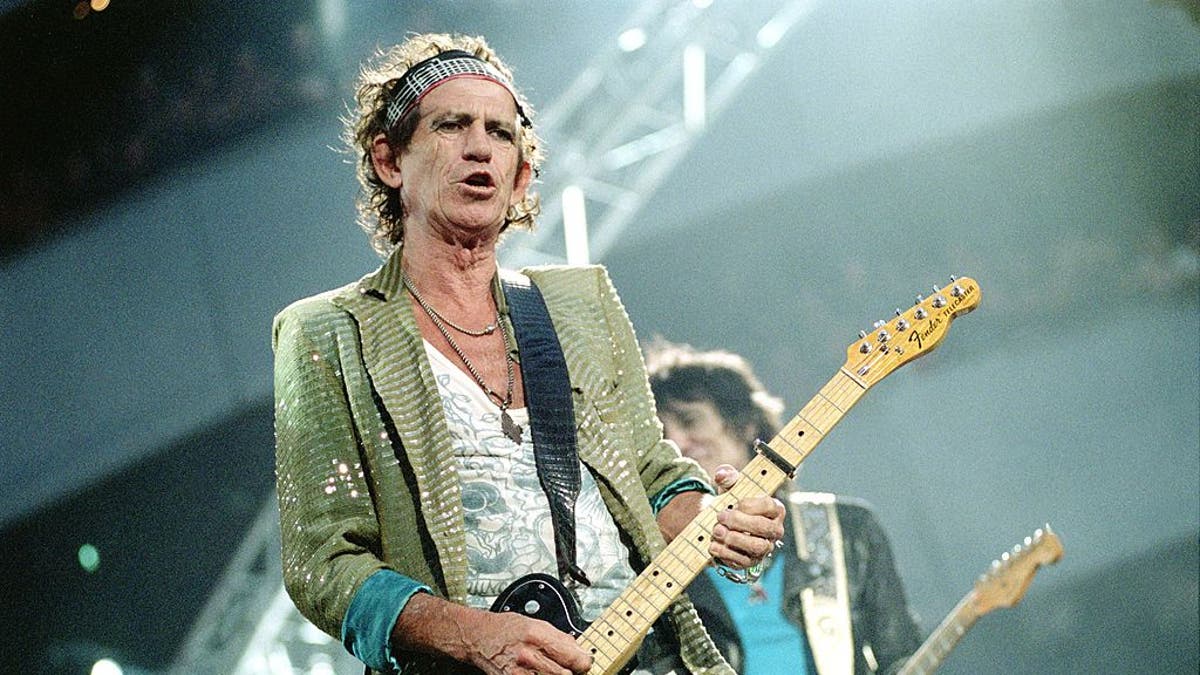

Keith Richards of The Rolling Stones in Amsterdam, Netherlands, on July 31, 2006. "If you don't know the blues … there's no point in picking up the guitar and playing rock ‘n’ roll," Richards has said. (Peter Pakvis/Redferns)

The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones — among many other British acts — cited American blues as their primary influence and inspiration.

"I loved rock ‘n’ roll," The Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards has said. "But then we found the blues."

Born in the Queen City crossroads

Mamie Robinson was born in Cincinnati on May 26, 1891. She married William "Smithy" Smith after moving to Harlem sometime around age 20 and kept her married name despite two more marriages later in life.

"The blues are America’s gift to the world." — rock ‘n’ roll historian Glenn Gass

She lived as a child at 14 Perry Street (now 308 Perry) in downtown Cincinnati, across from the present site of local landmark Duke Energy Convention Center.

The date of her birth was only recently discovered, Cincinnati outlet WKRC Local 12 reported in 2018, citing research into previously undiscovered census records. Her birthday has often been assumed to be 1883.

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO INVENTED THE ELECTRIC GUITAR AND INSPIRED ROCK ‘N’ ROLL

Little else is known about her family history.

Historians do know she grew up in a city that stood at the crossroads of American music at a time of great Black migration from south to north.

Jazz and blues singer Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds (including Willie "The Lion" Smith on piano) pose for a portrait circa 1920 in New York City. Smith performed "Crazy Blues," the first blues hit record, with Her Jazz Hounds in 1920. (Donaldson Collection/Getty Images)

The sounds of the Mississippi River came upstream to the Ohio River, while easterners moving westward in post-Civil War America passed through Cincinnati.

It made the riverfront city, on the cusp of north and south, a richly diverse mix of cultures and musical influences.

"The Delta Blues seemed to reflect the harsher environment of Mississippi at the time, a harsher work schedule, harsher punishments," Steven Tracy, a University of Massachusetts professor and author of "Going to Cincinnati: A History of the Blues in the Queen City," told Fox News Digital.

Chuck Berry performs his "duck walk" as he plays his electric hollowbody guitar at the TAMI Show on Dec. 29, 1964 at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium in Santa Monica, California. Other performers included James Brown, The Rolling Stones, The Beatles, and Jan and Dean. (Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

"People wandering the country brought different influences to Cincinnati. People there grew familiar with a different kind of blues."

Smith was likely influenced by genres such as New Orleans jazz and New York City ragtime, in addition to traditional delta field blues.

Smith possessed, in other words, fairly sophisticated musical tastes when she made her way to Harlem as a teenager.

She polished her act on the New York City vaudeville circuit. She sang, danced, even performed comedy.

"The blues are America's gift to the world," said rock ‘n’ roll historian and Indiana University professor emeritus Glenn Gass. Rock, he noted, is built upon the foundation laid by American delta blues. (Indiana University)

"By 1917, (Smith) was a seasoned entertainment professional with experience in Salem Tutt Whitney’s Smart Set musical comedy troupe and as a singer in New York nightspots, such as Barron Wilkins’ Exclusive Club," writes the Syncopated Times, a site devoted to traditional American music.

"She had thick hips, a lovely face and a regal self-presentation that exuded star quality."

She found her star-making moment in New York City in 1920.

Delta blues go mainstream

The origins of blues are evolutionary and unrecorded. The genre grew out of African-American spirituals, work songs and field chants of the Mississippi Delta. We don’t know who first sang the blues.

Lobby card from the movie "Sunday Sinners" (Colonnade Pictures), an all-Black-cast drama starring Edna Mae Harris, Alec Lovejoy and Mamie Smith, 1941. (John D. Kisch/Separate Cinema Archive/Getty Images)

But recordings with "blues" in the title are well documented and began to appear in the second decade of the 1900s.

W.C. Handy recorded blues instrumentals as early as 1914.

Some were eventually recorded with lyrics — but largely in the "crooner" style popular in the era. Handy’s "Memphis Blues," performed by Morton Harvey in 1915, is one notable example.

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO INVENTED THE GAS MASK AND MODERN TRAFFIC SIGNAL

It was called the blues. It didn't sound like the blues.

Smith's "Crazy Blues" is the first interpretation of the genre that listeners would recognize as blues today. It was written by Perry Bradford with the original title of "Harlem Blues."

Blues musician Muddy Waters photographed at Wilbraham Road Station in Manchester, England, while filming the Granada Television special "Blues And Gospel Train," on May 7, 1964. "The blues had a baby and the named it rock ‘n’ roll," Waters sang in 1977, explaining the connection between the two American-made musical genres. (GAB Archive/Redferns)

"In 1918, (Mamie Smith) was starring at the Lincoln Theater in ‘Made in Harlem’ (referred to in some texts as ‘Maid of Harlem'), a musical revue produced by Perry Bradford," writes the website Blackpast in its biography of Smith.

At Bradford's urging to OKeh Records, Smith was tapped to record "Crazy Blues" in August 1920.

Smith's pop-influenced vocals fueled the record's popularity and mainstream appeal.

Her "blues had polish, her wardrobe was lavish," notes the Blues Hall of Fame.

"Her flamboyance carried over into a luxurious lifestyle afforded by the sudden wealth she amassed. She bought three houses in New York, complete with fine accoutrements, servants, and, one visitor noted, ‘rugs on the floor as thick as mattresses.’"

She rode the success of "Crazy Blues" into a recording career that added a long list of follow-up hits.

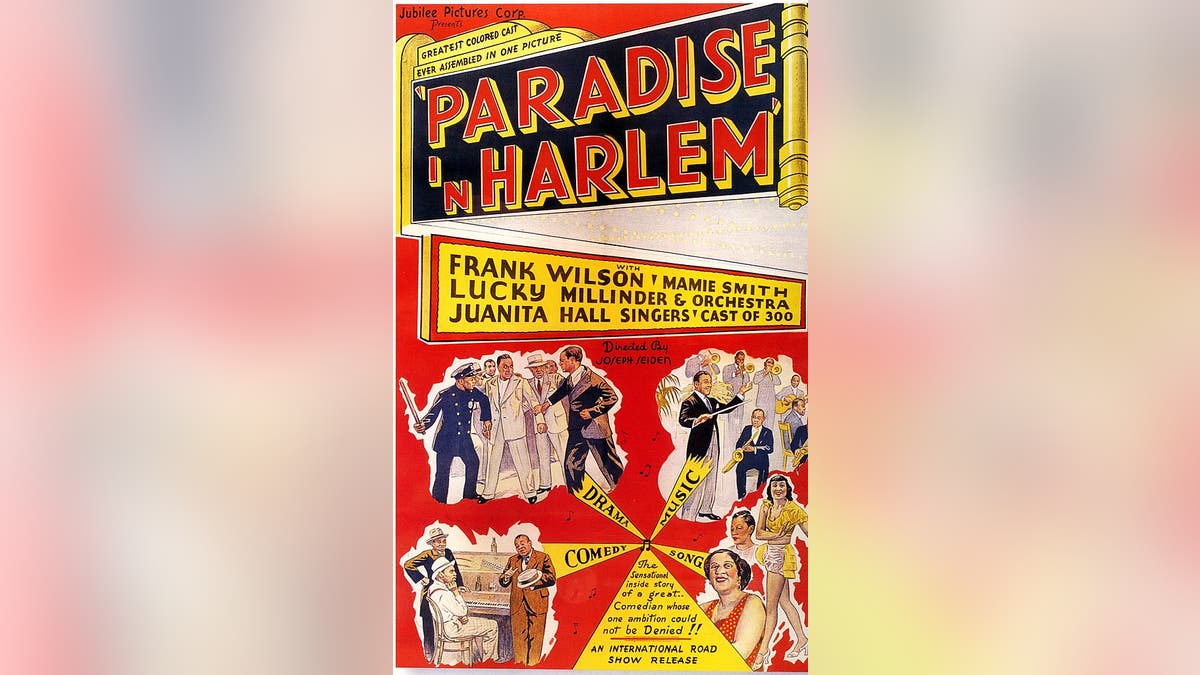

She eventually became a box-office draw. She starred in "Paradise in Harlem," her first film, in 1939, and "Because I Love You," her last role, in 1943.

Photo of Lucky Millander and Mamie Smith and film posters — "Paradise In Harlem." (GAB Archive/Redferns)

"We can say in hindsight that Mamie was more of a pop-blues singer," writes Steven Tracy. "Clearly, she was not, and did not intend to be, a low-down back porch Saturday night blues moaner, but she was a mature blues-infected singer of some power and depth."

Remembered by music community

Mamie Smith died in Harlem on Sept. 16, 1946, apparently suffering from an unknown illness.

She was 55 years old.

Her free-spending lifestyle took its toll. She was reportedly penniless when she died.

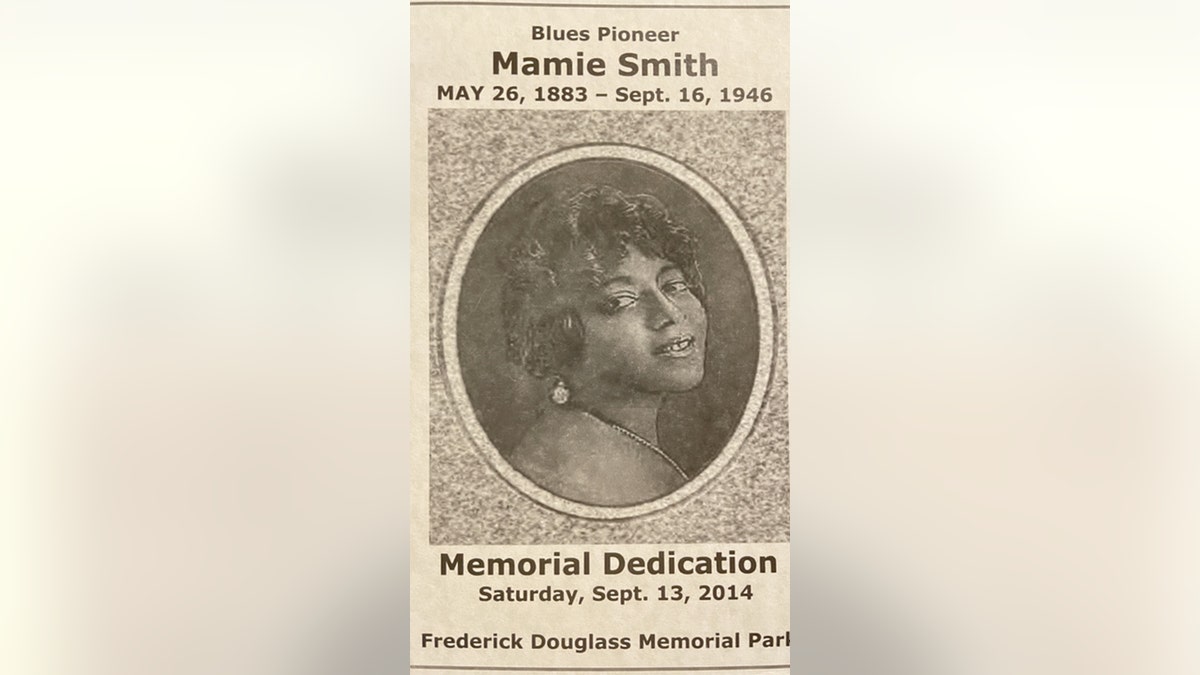

Blues pioneer Mamie Smith was buried in an unmarked grave on Staten Island when she died in 1946. Fans erected a gravestone in her honor in 2014. The date of her birth has since been shown to be May 26, 1891. Smith was just 55 years old when she died. (Kerry J. Byrne/Fox News Digital)

"Crazy Blues" joined the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1994 to honor records of historical significance.

It entered the Library of Congress National Recording Registry in 2005 — "America’s Jukebox," as some music authorities call it.

The registry honors songs that are "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant, and/or inform or reflect life in the United States."

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO POPULARIZED CHINESE FOOD IN THE US: IMMIGRANT CHEF JOYCE CHEN

She was buried in an unmarked plot in Frederick Douglass Memorial Cemetery on Staten Island.

A group of fans led by New York City blues journalist Michael Cala placed a gravestone over her previously unmarked burial site in 2014 amid great fanfare.

"By recording ‘Crazy Blues’ in 1920, she introduced America to vocal blues," reads the gravestone. It lists the long-suspected date of her birth as 1883, not the now-documented date of 1891.

The New York City music community, led by Michael Cala, held a ceremony in 2014 to unveil a headstone in Mamie Smith's honor above her previously unmarked gravesite. (Kerry J. Byrne/Fox News Digital)

The song, her epitaph continues, "opened the recording industry to thousands of African American brothers and sisters."

One of the most moving tributes to Smith’s influence is found in a nearby headstone of a design similar to Smith's. It belongs to New York City blues artist Michael Packer, who died in 2017.

"A Caucasian musician," cemetery administrator Virginia Footman told Fox New Digital. "He wanted to be buried near Mamie."

"I am the blues," reads his headstone.

One of the most moving tributes to Smith’s influence is found in a nearby headstone of a design similar to Smith's.

His faith in the blues is a sentiment shared by countless musicians and millions of music fans around the world, gripped by the raw human power of the genre.

"There is some poetic justice to the fact that Mamie was buried in Frederick Douglass Memorial Park Cemetery," writes Tracy.

Photo of Mamie Smith — posed studio portrait. She recorded the first blues song, "Crazy Blues," in 1920. Date unknown. (Gilles Petard/Redfern)

"She was, it must be admitted, regardless of opinions of her talent, a pioneer like Douglass, a person who made success possible for many others who followed."

Smith's pop sensibilities rounded off the hard edges of the blues.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR LIFESTYLE NEWSLETTER

She made the traditional rural moans of poverty-stricken sharecroppers in the Mississippi Delta accessible to a broad cross-section of urban Americans.

Put most simply, Mamie Smith changed global music.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Writes Cincinnati music historian Tracy: "She was, in fact, an ideal singer to throw the coming-out party for the blues."

To read more stories in this unique "Meet the American Who…" series from Fox News Digital, click here.