2020 presidential nominee Senator Kamala Harris (D-CA): What to know

Senator Kamala Harris announced her bid for the White House on Monday, January 21, Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Here’s what you need to know about her and her positions on major issues.

Kamala Harris began her 2020 presidential campaign with a sweeping anti-Trump speech on Jan. 27 that took pains to mollify progressive critics arguing that, when Harris was a prosecutor and California's attorney general, she shunned some of the same proposals she now claims are critical to stem racial injustice in the court system.

In the weeks since that address to supporters at Oakland City Hall, though, concerns from prominent progressives and members of the legal community back in California have only grown -- as has pressure on Harris to prove that her newfound commitment to these issues is genuine.

A scathing op-ed published in January in The New York Times, written by a law professor who directed the Loyola Law School Project for the Innocent in Los Angeles, kickstarted renewed scrutiny on Harris.

The law professor, Lara Bazelon, charged in the piece that Harris previously "fought tooth and nail to uphold wrongful convictions that had been secured through official misconduct that included evidence tampering, false testimony and the suppression of crucial information by prosecutors."

Bazelon further suggested that Harris should "apologize to the wrongfully convicted people she has fought to keep in prison and to do what she can to make sure they get justice," or otherwise make clear she has "radically broken from her past."

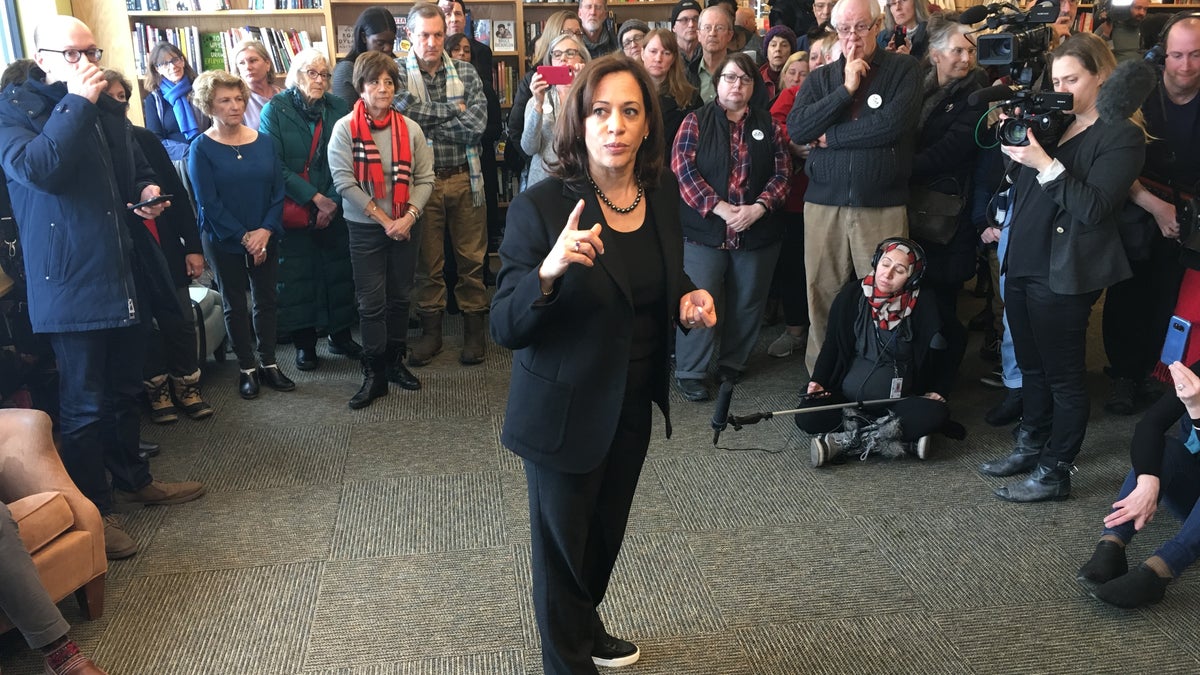

Sen. Kamala Harris talking to a crowd at Gibson's Bookstore in Concord, N.H. (Fox News)

Asked by Fox News this week whether she thought Harris has since taken the necessary steps to atone for her previous positions, Bazelon responded, "The short answer is no, I don’t."

"I am disappointed in Kamala Harris," Bazelon continued. "Her tenure as San Francisco district attorney and California attorney general was riven by the failures to embrace bold necessary change--or even change that wasn’t so bold but merely consistent with her prosecutorial mission--for example, conceding error on wrongful conviction cases rather than weaponize technicalities to keep people locked up."

Harris' "after-the-fact claim to have been a 'progressive prosecutor,'" Bazelon added, "rings hollow for the reasons I said in my [New York Times] piece." She cited shifting comments on marijuana and cash bail, adding: "What progressives like me want to see -- and have not -- is Harris reckon honestly with her record. ... I think voters are hungry for authenticity. It isn’t authentic to claim to be something you were not."

Other progressive advocates had a similar assessment. Just months after she joined the Senate in 2017, Harris touted her bipartisan bail reform package on Facebook, telling her thousands of followers that she wanted states to move away from cash bail entirely, and for judges to set bail amounts based only on the risks posed by defendants -- not the "money they’ve got in their bank account."

The goal, Harris said, was to reduce the effects of the bail system on impoverished minority communities. But her choice surprised some bail reform advocates back in California. In her seven years as a district attorney from 2004 to 2011, and then six as attorney general, Harris was absent on the issue, they say.

In fact, less than a year earlier, her office defended the cash bail system in a pair of federal court cases, shifting course only weeks before she entered the Senate.

"For her entire career, she used some of the highest money bail amounts in the country to keep people in jail cells and saddle poor families with financial debt," Alec Karakatsanis, an attorney who has brought several legal challenges to California's bail system, told The Associated Press. "And as soon as she had no influence on that issue practically, she announces she has a different view on it."

Harris' campaign did not respond to Fox News' request for comment.

JUST HOW MUCH MONEY HAS HARRIS RAISED SO FAR, COMPARED TO OTHER TOP DEM 2020 CONTENDERS?

Now a presidential candidate, Harris is casting herself as a progressive who consistently leveraged her power in the justice system to further civil rights causes and advocate for the disadvantaged. She has pledged a wholesale overhaul of the country's fractured criminal justice system, arguing for marijuana legalization, bail reform and a moratorium on the death penalty. But when she had a chance to take a bold stand on these issues as a top law enforcement officer, Harris often opted for a careful approach or defended the status quo.

In this Friday, March 8, 2019, photo, U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris, D-California, speaks at a town hall gathering in Hemingway, S.C. (AP Photo/Meg Kinnard)

"I never had a sense she was forward thinking or reforming," said John Raphling, a bail reform advocate and senior researcher at Human Rights Watch who faced off against Harris's state Justice Department as a criminal defense attorney. "Bail reform is a trendy issue, and a lot of politicians are jumping on it and saying this is unfair. I don't have any evidence that Harris was seeing that unfairness back when she was attorney general — but to her credit, we evolve, we learn, we see things."

Harris' supporters say as a prosecutor she was tasked with upholding the law and, as attorney general, defending the state, not making policy. She had limited ability to effect change within the rigid structure of the courts, they argue.

Argued Lateefah Simon, a civil rights activist who worked for Harris in San Francisco: "Everyone who has experienced the criminal justice system knows it's broken. She would say, 'we're confined by the rules of the law, and in the areas where we have discretion, we are going to work to try to move justice.'"

"I deeply know her convictions about what could be possible and what we needed to do, but also what the boundaries and limitations were," Simon said.

Senate Judiciary Committee members Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif., left, and Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., arrive at the chamber for the final vote to confirm Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, at the Capitol in Washington. (Associated Press)

Simon wrote a response to Bazelon's op-ed, which praised Harris for enacting "the first statewide implicit bias and procedural justice training in the country" and making "officers wear body cameras," as well as for starting "pattern and practice investigations into discriminatory actions" and demanding "that data on in-custody deaths and police shootings be made public to ensure accountability."

Simon also said Harris worked to hire more minority prosecutors. In her first year as San Francisco district attorney, she launched a re-entry program designed to keep low-level drug offenders from returning to prison. That same year she refused to seek the death penalty for a man who killed a police officer, infuriating the Bay Area political establishment and creating friction with the law enforcement community.

But in many cases throughout her career, Harris embraced the traditional role of prosecutor.

"I am disappointed in Kamala Harris."

She refused to take a position on a pair of sentencing reform ballot measures, arguing she must remain neutral because her office was responsible for preparing ballot text. She defended the death penalty in court, setting aside her personal opposition to capital punishment.

In response to critics who've pushed her to use her power in the courts to usher in change, she told The New York Times in 2016, "I have a client, I don't get to choose my client."

Harris now says she would call for a federal moratorium on the death penalty if elected president.

Harris' law enforcement approach has at times put her out of step with California's activist community. When she pushed a controversial policy that criminalized truancy, threatening to jail parents of children who missed too much school, even Harris' staff "winced at the plan," she wrote in her first book released just in time for her campaign for attorney general in 2010.

The program has since become a source of tension with criminal justice advocates, who see it as a sign of Harris' outdated approach to dealing with problems that stem from poverty. The Huffington Post recently spotlighted the case of a woman who was arrested under the program over her daughter's inconsistent school attendance -- though much of that was due to medical issues.

In a recent NPR interview, Harris said her truancy initiative was not designed to punish vulnerable families, but "put a spotlight" on the problem and direct resources to needy families. Her campaign hails the effort as a success, and supporters have lauded Harris for prioritizing a child's education.

"As a result of our initiative, which never resulted in any parent going to jail — never — because that was never the goal," Harris said.

But Harris' legacy remains on the state's books: She pushed a state-wide truancy law modeled after her San Francisco program. It has resulted in hundreds of parents in often less affluent and less politically liberal California counties being prosecuted.

Harris' approach at the time was considered smart politics for a politician seeking to run statewide. Throughout her career, Harris worked to win over powerful police unions. She refused to support a bill requiring her office to investigate shootings involving law enforcement officers. In 2015, she declined to back statewide standards for body cameras, arguing that individual departments should decide how to use the technology.

It is true, Bazelon conceded in her op-ed, that "politicians must make concessions to get the support of key interest groups," and that the "fierce, collective opposition of law enforcement and local district attorney associations can be hard to overcome at the ballot box." But, Bazelon charged, Harris "did not barter or trade to get the support of more conservative law-and-order types; she gave it all away."

As Harris transitioned from law enforcement to legislating, the politics of criminal justice issues were changing fast. The deaths of unarmed black men at the hands of police in 2014 and 2015 prompted outcry and spawned the nationwide Black Lives Matter movement. Democrats began rethinking their tough-on-crime strategies, focusing more on inequality and abuse in the system. Prosecutors and police came under increasing scrutiny for their roles.

Harris' views appear to have been changing, too.

In 2014, she was opposed to legalizing recreational marijuana, and when she ran against a Republican challenger for re-election as attorney general she took the more conservative view: He wanted to legalize. Harris laughed at the idea in a local television interview.

HARRIS SAID SHE LISTENED TO TUPAC WHILE SHE WAS HIGH IN COLLEGE, BEFORE HE EVEN MADE MUSIC

But Harris's public tone changed as speculation grew about her running for president in 2020. Last year, Harris endorsed Democratic Sen. Cory Booker's bill for federal legalization of marijuana. She argued on Twitter that "making marijuana legal at the federal level is the smart thing to do and it's the right thing to do." She released a video declaring that "marijuana laws are not applied and enforced in the same way for all people."

Last month, she went as far as acknowledging to a pair of morning radio hosts that she's used recreational marijuana: "I have, and I did inhale; that was a long time ago."

Some see a similar pattern when it comes to the call for bail reform. Shortly after announcing her presidential bid in January, Harris declared on Twitter: "It's long past time to address bail reform across the country."

"This is a serious injustice," she wrote.

Three years earlier, Harris's office was defending cash bail in a federal case. "Neither the bail law nor the bail schedule discriminate on the basis of wealth, poverty, or economic status of any kind," Harris wrote. In response to the notion that money bail schemes unfairly punish low-income defendants, Harris shot back, "the state is not constitutionally required to remove obstacles not of its own creation."

Harris appeared to have shifted her stance 10 months later. In December of 2016, Harris filed a motion in a case challenging the application of California's money bail laws saying the system is deserving "of intense scrutiny." She pledged not to defend any bail scheme that fails to take into account a defendant's ability to pay. Three weeks later she was sworn in to the Senate.

Still, she asked the judge to toss the case, arguing that the laws were constitutional even if the way some counties implemented those laws was not. "The bail system at issue here does not categorically deny bail to any group of individuals," she wrote.

The move perplexed bail reform advocates who say she could have used her position of power to do more as the top law enforcement official in the state, overseeing thousands of prosecutors who each day requested cash bail for those they charged with crimes.

"I'm glad she's come to the right position now, but it's too late for tens of thousands of Californians, real human beings who have been detained in jail every day in California throughout the whole state, that the attorney general could have stopped," Phil Telfeyan, one of the plaintiff's attorneys in the bail cases, told the AP.

Fox News' Andrew O'Reilly and The Associated Press contributed to this report.