Apollo 17, the last of the missions to land men on the moon, began 40 years ago today with the dawning of a man-made sun.

Lifting off just after midnight on Dec. 7, 1972, the Apollo 17 mission was the final of NASA's moon-bound manned flights — and the first night launch. The massive, 363-foot tall Saturn 5 rocket turned night into day as the long flames from its five powerful F-1 engines bathed the dark sky with a brilliant, bright-as-the-sun light that appeared to spectators to slowly climb skyward from the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Fla.

Onboard the mighty moon booster were three astronauts. Eugene Cernan, a veteran of two prior missions including the "dress rehearsal" for the first lunar landing three years earlier, commanded Apollo 17 and flew the lunar module "Challenger" to a landing in the Taurus-Littrow valley.

Ronald Evans served as the pilot of the command module "America" that remained in lunar orbit until it was time for the three voyagers to return to Earth. [Lunar Legacy: 45 Apollo Moon Mission Photos]

And lunar module pilot Harrison "Jack" Schmitt, who like Evans marked another first with the launch of Apollo 17 — his first time in space. That it was also the last time, to date, that anyone would embark for the moon, was less of a pressing concern.

- Cavemen trump modern artists at drawing animals

- Apollo 15: The ‘Moon Buggy’ Mission

- ‘Iron Dome’ for the US? Lockheed lasers destroy incoming missiles

- Country mourns Neil Armstrong, first man on the moon

- Apple’s next Macs will be made in the USA

- Best Western ever? Colorado hotel to become dinosaur playground

- Syrian government websites find suitable host in US servers

- Where are the moon walkers now?

[pullquote]

"I do not particularly recall at that time, prior to the launch, having thoughts that it was specifically the last mission," Schmitt told collectSPACE.com in an interview by phone this week. "I certainly don't think I felt any more pressure, nor do I think anybody did in that regard."

"These missions take on a life of their own, other than as we left the moon, when I think both [Cernan and I] had the awareness that it would be the last one, [judging] from our comments that we made on the surface," he added.

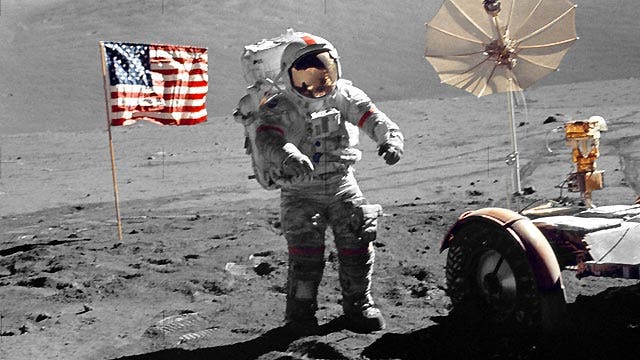

Landing at Taurus-Littrow four days after they launched, Cernan and Schmitt remained on the surface for just over three days, the longest duration lunar expedition to date. Like the two Apollo missions that preceded Apollo 17, the astronauts had a "moon buggy," the Lunar Roving Vehicle or lunar rover, to extend the distance they could traverse across the rocky valley.

Before leaving the moon, Cernan proclaimed, "America's challenge of today has forged man's destiny of tomorrow. And, as we leave the Moon at Taurus-Littrow, we leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind."

Apollo 17's legacy: more than just the last

Unlike being the first on the moon, the Apollo 17 mission's status as the last is temporary.

"Somebody will [return to the moon], it makes too much sense," Schmitt said. "Now, humankind has been able to ignore common sense in other circumstances. But when it comes to exploration, there really is a direct or indirect pressure on humans to continue."

When that day comes, whether it be through a government or commercial-led expedition, the emphasis on Apollo 17's legacy will change.

"From a scientific point of view, the [lunar] samples we brought back have played an important part in the ongoing debates on various aspects of lunar origin and evolution. But that's basically true of the samples from all six landing missions," said Schmitt. "Ours in particular, relate directly to evaluating hypotheses for the [moon's] origin because of the discovery of volcanic glass — the orange soil."

"There is orange soil!" Schmitt excitedly declared in 1972 while standing on the moon. "It's all over! Orange!"

The finest particles ever brought back from the moon, the microscopic glass beads with a distinctly orange tint, were created by volcanic processes early in the moon's history.

"That may turn out, if you consider the origin of the moon a primary question, to be very important," Schmitt stated, adding that the moon's geological history provides insight into the evolution of the Earth, when the "precursors to life were forming and potentially even life itself was getting started."

That Schmitt can remark on the scientific legacy of Apollo 17 points to another of the mission's legacies. He was the first scientist — a professional geologist — to launch on a NASA mission.

"I think from a space history perspective, the legacy of Apollo 17, for the U.S. and representing humankind, was putting the first trained, professional scientist onto the surface of another planet," Schmitt said. "Even though we were doing a good deal of training to bring the pilots up to speed, they were professional pilots and appropriately so during early Apollo [flights]. But then we finally started to recognize that people experienced and trained in other professions had a role in space."

"That was finally demonstrated with Apollo 17. It led to flying scientists on the Skylab [orbital workshop], and to having scientists and engineers, not the pilots, as a major component of the shuttle and space station programs," he added.

Looking back at Taurus-Littrow

Forty years later, Schmitt says there are still stories about Apollo 17 to be discovered, if you know where to look.

"There is a lot that has not been told," he remarked. "It is not that it is not available, because the [flight] transcripts are publicly available and basically they are the notes of the missions, as if I was taking handwritten notes, except I was doing it verbally and so were the other astronauts on the other missions. It just hasn't been looked at so that the public would be aware of the various stories and things that can be and are told in the transcripts."

NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), which since arriving in lunar orbit in 2009 has been returning imagery of the Apollo landing sites, including Taurus-Littrow, has also provided "various stories" about Apollo 17 — even some new to Schmitt.

"I have to admit to being surprised at how good the LRO camera is!" Schmitt stated. "It can pick up the dual tracks of the rover ... it is really quite remarkable." [Photos: New Views of Apollo Moon Landing Sites]

What perhaps is even more remarkable, is the verification that the lunar probe has provided to the planning that went into Apollo 17, 40 years ago.

"What the LRO photography has done... is [helped] look at the question of if we had LRO photography to plan the Apollo 17 mission, what would we have done differently?" said Schmitt. "And it turns out probably not much! With the photography we had, near as I can tell now, we picked the best places to go."