Kremlin-ordered assassinations: A history

Poisoned ex-spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter are likely the latest victims in a long line of Russia's Kremlin-ordered hits. Here is a look back at the victims of alleged Kremlin-ordered assassinations.

A Russian colonel turned British double agent found poisoned on a U.K. park bench Sunday is likely the latest victim in a long line of Kremlin-ordered hits against spies and dissidents, carried out with poison-tipped umbrellas, isotope-laced tea and bullets to the back of the head.

Sergei Skripal, a 66-year-old former Russian military intelligence officer, and his 33-year-old daughter, Yulia, are both in critical condition at a Salisbury-area hospital, as British police work to determine what “unknown substance” poisoned the pair. Posion has been a frequent weapon of death used by Russian intelligence agents, stretching back some 40 years.

British police in hazardous-materials suits have erected a tent over the bench where the two were found, and cordoned off a nearby Italian restaurant and pub as officers from numerous law enforcement agencies comb the area for evidence and review nearby surveillance cameras.

" ... this does certainly bear all the hallmarks of what the Russians call ‘wet work,’ or an assassination attempt.”

As they typically have in the past, the Russians are claiming they know nothing about what happened to Skripal and his daughter. Dmitry Peskov, the spokesman for President Vladimir Putin, insisted Moscow has no information about “this tragic situation,” and has offered to cooperate with the investigation.

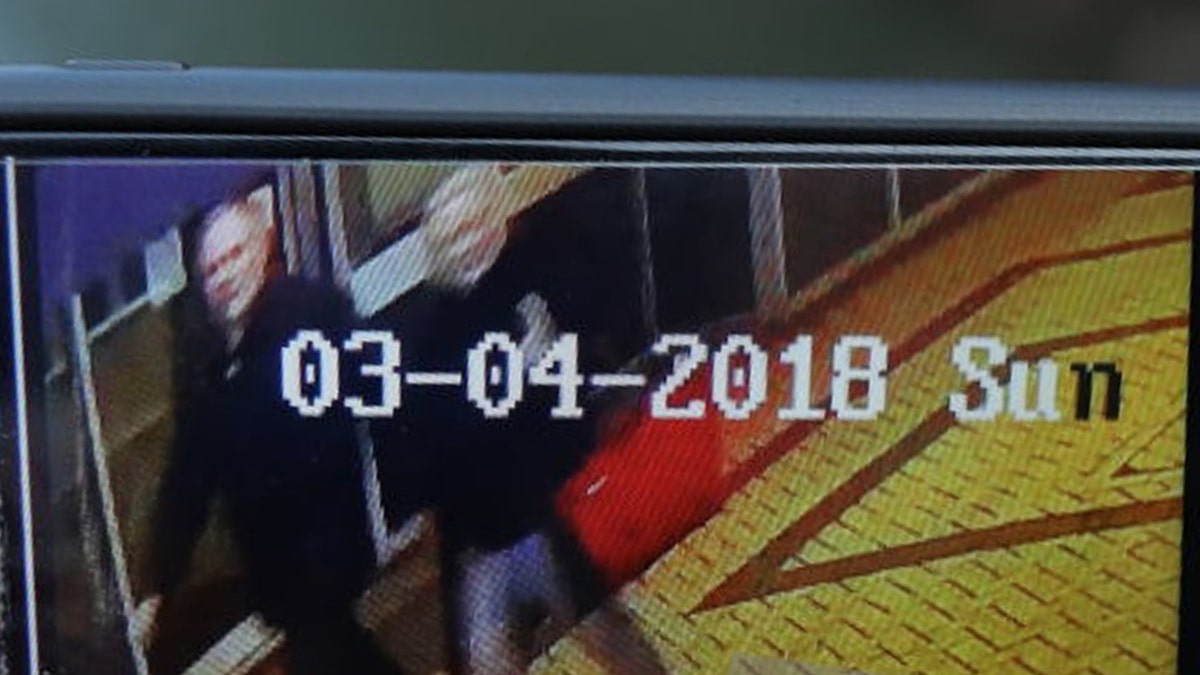

CCTV footage of Skripal shot shortly before he was possibly poisoned. (Getty Images)

But to many experts, the suspected poisoning bears all the classic signs of a Kremlin-backed hit.

“We have to have the caution that this could be just a particularly bad form of food poisoning,” Mark Galeotti, head of the Centre for European Security at the Institute of International Relations in Prague, told Fox News. “But this does certainly bear all the hallmarks of what the Russians call ‘wet work,’ or an assassination attempt.”

Russia’s shadowy spy agencies have over the decades found creative ways of offing their enemies, including the now-infamous 1978 poisoned-umbrella stabbing in London of dissident Bulgarian writer Georgi Markov.

Alexander Litvinenko, a former FSB officer who defected to London in 2000, was killed with isotope-laced tea. (AP Photo/Alistair Fuller)

Despite never being able to definitively pin the rubouts of Slavic spies and defectors on Putin and his predecessors and cronies, numerous former Russian secret agents have ended up dead under mysterious circumstances since Putin came to power in 1999.

The most infamous recent assassination was that of Alexander Litvinenko, a former intelligence officer who defected to London in 2000, after publicly accusing his superiors of hatching and assassination plot against a Russian oligarch. While in London, Litvinenko worked as a consultant for British intelligence, and wrote two books that were harshly critical of Putin.

Litvinenko fell ill in November 2006, and died soon thereafter. His death was attributed to drinking tea poisoned with radionuclide polonium-210, after the British Health Protection Agency found significant amounts of the rare and highly toxic substance in his body. A judicial inquest ruled in 2016 that there was a “strong probability” Litvinenko’s death was a Russian intelligence operation that was probably approved by Putin himself.

“I think we have to remember that Russian exiles aren’t immortal,” Mark Rowley, assistant commissioner of the Metropolitan Police Service and Britain’s chief counterterrorism officer, told BBC radio.” They do all die, and there can be a tendency for some conspiracy theories. But likewise, we have to be alive to the fact of state threats, as illustrated by the Litvinenko case.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin has been blamed for ordering numerous assassinations of critics and defectors. (The Associated Press)

It’s not just defectors from Russia’s espionage services who have been apparently marked for death by Putin. In the last four years alone, dozens of high-profile Russians – including journalists, anti-corruption experts and politicians – have all died under suspicious circumstances.

In 2015, the former media director of Russia energy company Gazprom and founder of the RT television network, Mikhail Lesin, was discovered dead by a blow to the head inside a Washington, D.C., hotel room. In July 2016, Belarusian-born Russian journalist and Putin critic Pavel Sheremet was killed in a car bombing in the Ukrainian capital of Kiev.

“Russian intelligence agencies going back to the 19th century have always been more willing than their western counterparts to carry out assassinations abroad,” Galeotti said. “This culture, along with the geopolitical pressure on Russia and the increasing role the FSB has taken in operations abroad, all play a role in the Kremlin increasingly using assassination as a play in its toolbox.”

A still image taken from an undated video shows Sergei Skripal, a former colonel of Russia's GRU military intelligence service, being detained by secret service officers in an unknown location. (RTR/via Reuters TV)

Along with attacks abroad, scores of Putin critics also have been silenced by shootings, beatings, poisonings and other means in Russia. In one of the more horrifying episodes, Boris Nemtsov – physicist and liberal politician – was gunned down just feet from the Kremlin in 2015, only hours after calling for a march against Russia’s war in the Ukraine.

In Skripal’s case, the former Russian military intelligence officer was granted asylum in Britain after spending four years in a Moscow jail on treason charges. He was one of four men exchanged in a 2010 high-profile spy swap that sent 10 Russian sleeper agents held in the U.S. back home.

Until 1999, Skripal worked for GRU - Russian military intelligence - before being transferred to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. While he retired in 2003 to go into private business, he was arrested and jailed in 2006 after admitting to selling the names, addresses and code-names of dozens of Russian spies to MI6 in exchange for large sums of cash.